Houston’s Love for Immersive Art Isn’t Entirely FOMO

Image: Courtesy MFAH

It comes every Houston summer, along with the cicadas, Astros anxiety, and punishing heat. The inescapable wave of social media pics documenting trips to the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston (MFAH), with friends and family posing alongside—or even inside—the latest installation exhibit. Clamoring up and down complex bamboo structures or reclining around glowing plastic orbs. Excited faces and exaggerated poses, enough to tempt you to want to head off to the museum and experience the same fun for yourself. You don’t want to miss out, after all, and you’ll be supporting an integral local arts institution to boot. Win-win.

At first glance, this seems like a brilliant social media strategy. And it objectively is: word of mouth is a powerful tool in any marketing department’s arsenal. One could easily assume that social media drives public interest in immersive installation artworks, creating a demand that artists and arts organizations scramble to fulfill. But the reality is, as MFAH director Gary Tinterow says, “not a causal relationship.”

“Instagram, Twitter, Reels, before that Tumblr, YouTube. These were all vehicles for promoting awareness of immersive exhibitions, whether they’re at art museums, or they’re in commercial spaces. So the social media and people posting fuels awareness of these projects,” he says. “At the same time, it’s artists who are creating the objects that enable us to exhibit them in the first place. We don’t make exhibitions so that they can be posted on social media… But it is true that people come to experience our immersive exhibitions and they post about them. Therefore, more people come.”

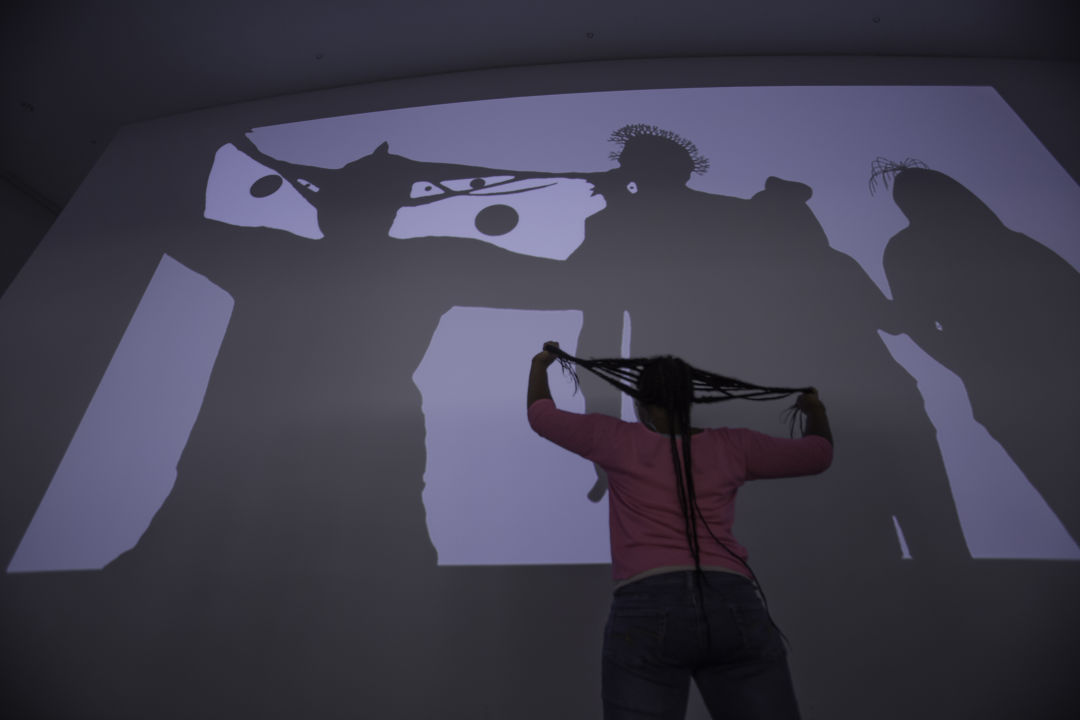

He notes that MFAH typically schedules their family-friendly installation exhibits in the summer so grandparents, parents, and kids can experience them together. The most well-attended events were 2014’s Soto: The Houston Penetrable, which attracted 130,852 people, and 2015’s Shadow Monsters, which brought in 126,221.

Image: Carrithers Studio

More recently, the museum presented Pipilotti Rist’s Pixel Forest and Worry Will Vanish in 2023. Visitors walked through a “forest” consisting of large, playful multicolored LEDs and lounged on beanbag chairs while a fantasy of nature and bodies and the heavens played out on videos around them. MFAH also acquired Yayoi Kusama’s infinity room The Aftermath of Obliteration of Eternity, which feels like the prelude to an encounter with a powerful cosmic force, as an ongoing exhibit.

Tinterow points out that although the MFAH’s installation pieces oftentimes seem ubiquitous on social media, the museum’s most-visited exhibition was actually Hockney–Van Gogh: The Joy of Nature in 2021, which consisted of “paintings, drawings, and one immersive space.” The decision to display installation art didn’t come from the number of Houstonians coming in the doors, but rather from what artists were already doing.

“I would say that [installation art] is a phenomenon that’s pervasive in the contemporary art world today. So we’re following,” he says. “We can only exhibit what is made. It’s clear that a lot of artists are working in this experiential dimension.”

Multimedia artist JooYoung Choi, whose vibrant puppetry and video works have earned accolades from the likes of legendary director and Muppeteer Frank Oz, agrees that while she feels grateful for the excitement social media provides artists, first and foremost she makes things that she wants to see.

Choi never considered working in the installation art space until she moved to Houston. She studied painting while working on her undergraduate degree at Massachusetts College of Art and Design and later her masters at Art Institute of Boston. She experimented a little with video and animation while in grad school, but credits DiverseWorks curator Rachel Cook with stoking an interest in immersive, interactive artistic experiences.

“Rachel came to my studio and just loved how I organized everything. I didn’t have a flat file back then. I used to put things in empty pizza boxes and label them and have them in a big stack… I us[ed] clothes hangers to clip big pieces of art onto them,” she says. “And she got a kick out of how I organized my makeshift space… She said, ‘Let’s just install your whole art studio into DiverseWorks.’”

Choi was hooked. The experience of installing and displaying her entire studio, and watching visitors interact with it, broadened the scope of what she understood to be art.

As her art took off on social media, so too did her opportunities. She received an invitation for her first major museum exhibition in Houston while shopping for guacamole at Fiesta, from a curator who saw photos on Facebook.

And while social media doesn’t shape her final creative decisions, the social element that inspires art enthusiasts to post photos of themselves alongside immersive works certainly inspires her in kind. Her piece Like a Bolt Out of the Blue, Faith Steps In and Sees You Through, which was previously shown at Moody Center for the Arts and the Art Museum of Southeast Texas, asks visitors to write wishes on paper stars using black light–responsive ink. They can then walk through with a black-light flashlight and find connections and community with the previous wishes hung up for display.

“This child was wishing for a baby brother. This other person was writing about how they wish that they’ll be able to conceive a child and have a family,” she says. “It’s been incredible for me to be able to watch people feel like they can own a piece of the art, and that it goes to a place where they need to go versus what I was thinking… [There are] really moving moments where people would write things that I would have never considered. It’s almost like your art takes on a life of its own.”

Choi likens her forays into immersive installation art to her childhood marveling at Nintendo games and the Peter Pan ride at Disney theme parks. Though overlooked as such, these are themselves artistic endeavors, and terms like “immersive” and “installation” sound deceptively contemporary. Immersive and installation pieces have never not been a part of art history, for as long as there has been art history.

“Visiting a great church or cathedral in Europe. Hearing the organ play, hearing monks chanting, smelling the incense is an immersive experience. Any great architectural experience, like the Pantheon in Rome, is by nature immersive,” Tinterow points out. “Going to visit Mayan temples in the Yucatán is immersive. All your senses are engaged, including your leg muscles. I think that there has always been art and environments which appeal to multiple senses at the same time, which is really the definition of immersive.”