Skolem normal form

In mathematical logic, reduction to Skolem normal form (SNF) is a method for removing existential quantifiers from formal logic statements, often performed as the first step in an automated theorem prover.

A formula of first-order logic is in Skolem normal form (named after Thoralf Skolem) if it is in prenex normal form with only universal first-order quantifiers. Every first-order formula may be converted into Skolem normal form while not changing its satisfiability via a process called Skolemization (sometimes spelled "Skolemnization"). The resulting formula is not necessarily equivalent to the original one, but is equisatisfiable with it: it is satisfiable if and only if the original one is satisfiable.[1]

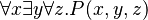

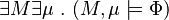

The simplest form of Skolemization is for existentially quantified variables which are not inside the scope of a universal quantifier. These may be replaced simply by creating new constants. For example,  may be changed to

may be changed to  , where

, where  is a new constant (does not occur anywhere else in the formula).

is a new constant (does not occur anywhere else in the formula).

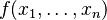

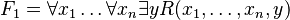

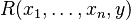

More generally, Skolemization is performed by replacing every existentially quantified variable  with a term

with a term  whose function symbol

whose function symbol  is new. The variables of this term are as follows. If the formula is in prenex normal form,

is new. The variables of this term are as follows. If the formula is in prenex normal form,  are the variables that are universally quantified and whose quantifiers precede that of

are the variables that are universally quantified and whose quantifiers precede that of  . In general, they are the variables that are quantified universally[clarification needed] and such that

. In general, they are the variables that are quantified universally[clarification needed] and such that  occurs in the scope of their quantifiers. The function

occurs in the scope of their quantifiers. The function  introduced in this process is called a Skolem function (or Skolem constant if it is of zero arity) and the term is called a Skolem term.

introduced in this process is called a Skolem function (or Skolem constant if it is of zero arity) and the term is called a Skolem term.

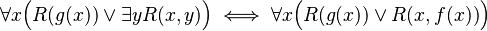

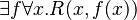

As an example, the formula  is not in Skolem normal form because it contains the existential quantifier

is not in Skolem normal form because it contains the existential quantifier  . Skolemization replaces

. Skolemization replaces  with

with  , where

, where  is a new function symbol, and removes the quantification over

is a new function symbol, and removes the quantification over  . The resulting formula is

. The resulting formula is  . The Skolem term

. The Skolem term  contains

contains  , but not

, but not  , because the quantifier to be removed

, because the quantifier to be removed  is in the scope of

is in the scope of  , but not in that of

, but not in that of  ; since this formula is in prenex normal form, this is equivalent to saying that, in the list of quantifiers,

; since this formula is in prenex normal form, this is equivalent to saying that, in the list of quantifiers,  precedes

precedes  while

while  does not. The formula obtained by this transformation is satisfiable if and only if the original formula is.

does not. The formula obtained by this transformation is satisfiable if and only if the original formula is.

Contents

How Skolemization works

Skolemization works by applying a second-order equivalence in conjunction to the definition of first-order satisfiability. The equivalence provides a way for "moving" an existential quantifier before a universal one.

where

is a function that maps

is a function that maps  to

to  .

.

Intuitively, the sentence "for every  there exists a

there exists a  such that

such that  " is converted into the equivalent form "there exists a function

" is converted into the equivalent form "there exists a function  mapping every

mapping every  into a

into a  such that, for every

such that, for every  it holds

it holds  ".

".

This equivalence is useful because the definition of first-order satisfiability implicitly existentially quantifies over the evaluation of function symbols. In particular, a first-order formula  is satisfiable if there exists a model

is satisfiable if there exists a model  and an evaluation

and an evaluation  of the free variables of the formula that evaluate the formula to true. The model contains the evaluation of all function symbols; therefore, Skolem functions are implicitly, existentially quantified. In the example above,

of the free variables of the formula that evaluate the formula to true. The model contains the evaluation of all function symbols; therefore, Skolem functions are implicitly, existentially quantified. In the example above,  is satisfiable if and only if there exists a model

is satisfiable if and only if there exists a model  , which contains an evaluation for

, which contains an evaluation for  , such that

, such that  is true for some evaluation of its free variables (none in this case). This may be expressed in second order as

is true for some evaluation of its free variables (none in this case). This may be expressed in second order as  . By the above equivalence, this is the same as the satisfiability of

. By the above equivalence, this is the same as the satisfiability of  .

.

At the meta-level, first-order satisfiability of a formula  may be written with a little abuse of notation as

may be written with a little abuse of notation as  , where

, where  is a model,

is a model,  is an evaluation of the free variables, and

is an evaluation of the free variables, and  means that

means that  is true in

is true in  under

under  . Since first-order models contain the evaluation of all function symbols, any Skolem function

. Since first-order models contain the evaluation of all function symbols, any Skolem function  contains is implicitly, existentially quantified by

contains is implicitly, existentially quantified by  . As a result, after replacing an existential quantifier over variables into an existential quantifiers over functions at the front of the formula, the formula still may be treated as a first-order one by removing these existential quantifiers. This final step of treating

. As a result, after replacing an existential quantifier over variables into an existential quantifiers over functions at the front of the formula, the formula still may be treated as a first-order one by removing these existential quantifiers. This final step of treating  as

as  may be completed because functions are implicitly existentially quantified by

may be completed because functions are implicitly existentially quantified by  in the definition of first-order satisfiability.

in the definition of first-order satisfiability.

Correctness of Skolemization may be shown on the example formula  as follows. This formula is satisfied by a model

as follows. This formula is satisfied by a model  if and only if, for each possible value for

if and only if, for each possible value for  in the domain of the model, there exists a value for

in the domain of the model, there exists a value for  in the domain of the model that makes

in the domain of the model that makes  true. By the axiom of choice, there exists a function

true. By the axiom of choice, there exists a function  such that

such that  . As a result, the formula

. As a result, the formula  is satisfiable, because it has the model obtained by adding the evaluation of

is satisfiable, because it has the model obtained by adding the evaluation of  to

to  . This shows that

. This shows that  is satisfiable only if

is satisfiable only if  is satisfiable as well. In the other way around, if

is satisfiable as well. In the other way around, if  is satisfiable, then there exists a model

is satisfiable, then there exists a model  that satisfies it; this model includes an evaluation for the function

that satisfies it; this model includes an evaluation for the function  such that, for every value of

such that, for every value of  , the formula

, the formula  holds. As a result,

holds. As a result,  is satisfied by the same model because one may choose, for every value of

is satisfied by the same model because one may choose, for every value of  , the value

, the value  , where

, where  is evaluated according to

is evaluated according to  .

.

Uses of Skolemization

Lua error in package.lua at line 80: module 'strict' not found.

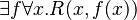

One of the uses of Skolemization is automated theorem proving. For example, in the method of analytic tableaux, whenever a formula whose leading quantifier is existential occurs, the formula obtained by removing that quantifier via Skolemization may be generated. For example, if  occurs in a tableau, where

occurs in a tableau, where  are the free variables of

are the free variables of  , then

, then  may be added to the same branch of the tableau. This addition does not alter the satisfiability of the tableau: every model of the old formula may be extended, by adding a suitable evaluation of

may be added to the same branch of the tableau. This addition does not alter the satisfiability of the tableau: every model of the old formula may be extended, by adding a suitable evaluation of  , to a model of the new formula.

, to a model of the new formula.

This form of Skolemization is an improvement over "classical" Skolemization in that, only variables that are free in the formula are placed in the Skolem term. This is an improvement because the semantics of tableau may implicitly place the formula in the scope of some universally quantified variables that are not in the formula itself; these variables are not in the Skolem term, while they would be there according to the original definition of Skolemization. Another improvement that may be used is applying the same Skolem function symbol for formulae that are identical up to variable renaming.[2]

Another use is in the resolution method for first order logic, where formulas are represented as sets of clauses understood to be universally quantified. (For an example see drinker paradox.)

Skolem theories

In general, if  is a theory and for each formula

is a theory and for each formula  with free variables

with free variables  there is a Skolem function, then

there is a Skolem function, then  is called a Skolem theory.[3] For example, by the above, arithmetic with the Axiom of Choice is a Skolem theory.

is called a Skolem theory.[3] For example, by the above, arithmetic with the Axiom of Choice is a Skolem theory.

Every Skolem theory is model complete, i.e. every substructure of a model is an elementary substructure. Given a model M of a Skolem theory T, the smallest substructure containing a certain set A is called the Skolem hull of A. The Skolem hull of A is an atomic prime model over A.

See also

- Herbrandization, the dual of Skolemization

- Predicate functor logic

Notes

- ↑ Lua error in package.lua at line 80: module 'strict' not found.

- ↑ R. Hähnle. Tableaux and related methods. Handbook of Automated Reasoning.

- ↑ [1]

References

- Lua error in package.lua at line 80: module 'strict' not found.

External links

- Lua error in package.lua at line 80: module 'strict' not found.

- Skolemization on PlanetMath.org

- Skolemization by Hector Zenil, The Wolfram Demonstrations Project.

- Weisstein, Eric W., "SkolemizedForm", MathWorld.