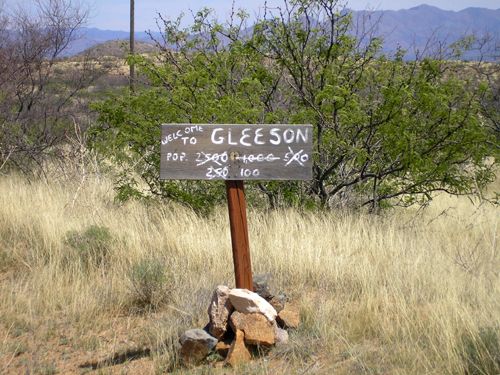

Welcome to Gleeson, Arizona. Though the sign indicates a population of 100, we didn’t see a soul by Kathy Alexander.

The Ghost Town Trail begins on a dusty road winding out of Tombstone, Arizona. After traveling some 16 miles along this historic path, you’ll come to the ghost town of Gleeson, Arizona. Situated on the south side of the Dragoon Mountains, Gleeson was first inhabited by Indians who mined the area for its decorative turquoise.

When white prospectors began to move into the area, they found copper, lead, and silver in the area, and before long, a mining camp sprouted up in the hills above where Gleeson stands today. The first camp was called Turquoise when a post office opened in 1890. However, just four short years later, when Jimmie Pearce found gold at the Commonwealth claim in what would become Pearce, the town of Turquoise was abandoned, and the post office closed.

Gleeson, Arizona

Then, in 1900, a Pearce miner named John Gleeson began prospecting the Turquoise area again. Finding large deposits of copper, he soon filed several claims and opened the Copper Belle Mine. More miners flooded the area quickly, and new mines with names like Silver Belle, Brother Jonathan, Defiance, and Pejon also sprouted up. The new mining camp, Gleeson, moved down the hill to be closer to water. On October 15, 1900, the post office opened, supporting a population of about 500, almost all working in the mines.

In 1912, a fire raged through Gleeson, taking some 28 buildings with it. However, with the mines still producing ore in large volumes, it was quickly rebuilt. John Gleeson sold out in 1914, but copper production flourished, especially during World War I. After the war, however, copper prices began to fall, ore production decreased, and by the 1930s, the mines had all shut down. Most of the population moved on, but Gleeson’s post office held on until March 31, 1939, when it, too, shut its doors, and Gleeson became a ghost town.

Today, the old settlement still supports a couple of residents and numerous ruins, including a hospital, a saloon, a dry goods store, several houses, a jail, numerous mining remnants, and the large foundation of what was once a large school. The Gleeson cemetery is just west of the town on the road to Tombstone.

Continue your trek through Gleeson on Gleeson Road. You will come to Ghost Town Trail Road, just a mile beyond the town, turning north to continue to Courtland and Pearce. The dusty road contains remnants of the area’s more prosperous past. Courtland is just about 3.5 miles down the road.

Courtland, Arizona

Interestingly, though Courtland started later than nearby Gleeson, it grew to four times the size. Even more interesting is that this once larger town, which died later than its nearby neighbor, has far fewer remains.

Getting its start in the early 1900s, miners flooded the area to work for the Copper Queen, Leadville, Great Western, Calumet, and Arizona Mining Companies. One of the largest companies, the Great Western, was owned by W.J. Young, who named the quickly growing settlement for his brother Courtland.

In March 1909, a post office was established. Before long, the town boasted a population of 2,000 residents who supported two newspapers, several stores, a Wells Fargo office, and the Southern Arizona Auto Company.

The Mexico and Colorado Railroad also arrived from Douglas. The town provided a movie theater, an ice cream parlor, a pool hall, and a swimming pool for amusement.

But, like the other area mining towns, Courtland’s mines played out, and so did the town. Though it hung on through the Great Depression, its post office finally closed in 1942. By then, many of its buildings had already been razed or moved. What was left was quickly claimed by the desert.

Today, Courtland’s only remains are the old jail, a collapsing store, several foundations, and plenty of mining evidence testifying to its more prosperous times. The hills surrounding Courtland are pocked with mines and old shafts, so visitors should beware that hiking in the area could be hazardous.

Another 10 ½ miles down the road, you will come to Pearce, the only one of these three ghost towns that continue to maintain its post office.

Pearce, Arizona

The Pearce General Store has been restored and is on the National Register of Historic Buildings, Kathy Alexander.

Pearce was also the first of the three towns to get its start when a man named Jimmie Pearce discovered gold. He wasn’t even looking for it! In fact, Jimmie, who had been a miner in Tombstone and ran a boarding house with his wife, had decided to retire from the mining business. After carefully saving their money, they purchased some ranch land in the Sulphur Springs Valley northeast of Tombstone and settled down to the ranching life along with their three children.

But it wouldn’t be for long. In 1894, while out on his ranch, he found gold lying on the side of a hill. He wasted no time taking it to Tombstone to be assayed and was heartened to hear that it showed a high ore content of gold and silver. All five family members immediately began to file mining claims on their land, and Jimmie Pearce was back in the mining business, albeit as an owner rather than an employee. He called his new mine the Commonwealth, and the area flooded with new residents when word spread of his find.

Jimmie Pearce, however, didn’t stay in business long. He sold the Commonwealth Mine for $250,000 to John Brockman. But, remembering some of the hard times they had through in the past, his wife insisted on a clause in the contract that guaranteed her the right to run a boardinghouse beside the mine.

A post office opened in March 1896, and soon dozens of other businesses followed, including the Soto Brothers & Renaud General Store, which still stands today. Listed on the National Register of Historic Buildings, the old structure has been lovingly restored, providing a highly accurate view of the past. Though the store is not open for business, stopping for a photo opportunity is necessary.

Peak production of the Commonwealth Mine was realized quickly in 1896, but it would continue to operate for years. Other businesses included a school, hotels, several saloons, and a motion-picture theater. Many of the town’s early buildings were transported over the mountains from Tombstone. The population of Pearce increased to 1500 residents.

Like other mining towns, Pearce was not always peaceful, as miners and cowboys made their way to the new boom town. Though never as lawless as Tombstone, Pearce needed a constable and, in 1896, hired George Bravin, who hired a tough deputy named Burton Alvord. At that time, Alvord still had a reputation as a fearless lawman. Later, Alvord joined up with Billy Stiles, and the two formed the Alvord-Stiles Gang, robbing trains throughout Arizona Territory and often using Pearce as their headquarters. But, in 1896, Alvord had not yet begun his crime spree, and after working as a Pearce deputy for about six months, Bravin decided that there was no longer a need for the toughened lawman, and Alvord moved on the Willcox. There, Alvord would gain a reputation as a killer and, by the turn of the century, would be robbing trains.

Ironically, George Bravin, who by 1900 had moved to Tombstone as a lawman, would again come face to face with Burt Alvord inside his jail. There, Billy Stiles would help Alvord to escape and, in the resulting melee, would shoot off two of Bravin’s toes.

Commonwealth Mine, 1910.

In Pearce, the new Commonwealth mine owner, John Brockman, built a 200-stamp mill. With the rampant thievery throughout the territory, the mine deliberately formed their gold bars so heavy that they could not be carried out on horseback. The stamp mill burned to the ground in 1900; however, business was so good that they soon built another. Brockman continued to operate the mine for two more years until he sold it in 1902. In 1904, a cave-in caused the mine to shut down temporarily. But, the shutdown was brief, and the following year, a cyanide plant was erected, and another fortune was made extracting the tailings.

The Great Depression took its toll, and in the early 1930s, the mine closed, and the railroad pulled up its tracks. Over the years, the Commonwealth Mine was one of the richest in Arizona, producing over 15 million dollars in Gold.

In the meantime, Pearce became a ghost town. Only a few residents remain in the area, and most of its buildings are gone, but Pearce hangs on. The old post office, decommissioned in the late 1960s, is now a private residence. The historic general store will be re-opening in the Fall of 2007. Another business, Old Pearce Pottery, operates out of another historic building. The area is seeing a rejuvenation as retirees and others are attracted to the climate and are buying real estate.

Several other remains from the past can be seen, including a school, the old jail, several ruins and foundations, and the Pearce cemetery west of town on Middlemarch Road. This historic path crosses the Dragoon Mountains into Tombstone for those seeking a more adventurous trek. The old road was once commonly used by soldiers between Fort Bowie and Fort Huachuca in the 1870s and 1880s.

To access the Ghost Town Trail from Tombstone, take the well-marked turnoff for Gleeson Road heading east and follow for about 15 miles to Gleeson. A mile beyond Gleeson, turn left onto Ghost Town Trail and continue to Courtland and Pearce. Drive northwest from Pearce to reconnect with Interstate 10. Some of the routes are unpaved but suitable for passenger cars.

©Kathy Alexander/Legends of America, updated July 2024.

See our Ghost Town Trail Photo Gallery HERE

Also See:

Arizona Ghost Towns and Mining Camps

Arizona – The Grand Canyon State

Ghost Towns & Mining Camps Across America

Tombstone, Arizona – The Town Too Tough To Die

See Sources.