Newport, Rhode Island by Doug Kerr, Flickr

Newport, Rhode Island, is located at the southern end of Aquidneck Island and sits at the entrance to Narragansett Bay. This seaside city has the Newport National Historic Landmark District, which tells much of its more than three-century-old history.

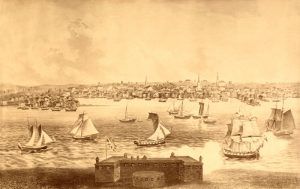

Historic Newport, Rhode Island by 6SN7, Flickr

The historic district was designated a National Historic Landmark in 1968 due to its extensive and well-preserved assortment of intact colonial buildings dating from the early and mid-18th century. Six of those buildings are National Historic Landmarks in their own right, including the city’s oldest house and the former meeting place of the colonial and state legislatures. Covering some 250 acres, the historic district sits in the center of Newport, roughly bounded by Kingston, Bellevue, Pope, Thames, Bridge, and Van Zandt Streets.

Newport, Rhode Island, was founded in May 1639 by a small band of men from Massachusetts under the leadership of John Clarke and William Coddington. Among other early settlers were the Clarkes, Brentons, Coddingtons, and Eastons. Cultured, wealthy, and with high political and social standing in England and the colonies, these settlers explicitly embraced religious freedom, tolerance, and separation of church and state. Language to that effect appeared in the statutes drawn up in 1640, and John Clarke is credited with drafting similar text for the Rhode Island Colony Charter of 1663. This liberal outlook set Newport, like Providence, founded on religious freedom in 1636, apart from other New England colonies, both in the people it attracted and the favorable climate for commerce it created. The town’s diverse religious identity figured prominently in commercial associations, family relations, government, and physical plan development patterns.

Early industries were farming, fishing, and shipbuilding. By 1680, Newport had become a thriving seashore town of some 400 houses arranged in a still-legible, irregular network of streets along the harbor and the hill, covering at least a mile in length. Houses of the initial settlement period were similar to other Rhode Island and New England 17th-century dwellings, which were modest-scale, blocky, wood structures with gable roofs, large chimneys, and small windows. The form is derived from English precedents. Approximately ten 17th-century houses survive in Newport and are valuable records of early building traditions, although all were altered and expanded by later additions.

Construction of wharves occurred simultaneously with the building of the first houses, and by 1680, Newport merchants had formed “The Proprietors of the Long Wharf” to promote shipping. Early industries supporting the agricultural/maritime economy included grist and sawmills, tanneries, cooperages, ropewalks, breweries, and bakeries. The town supported shipwrights, housewrights, blacksmiths, masons, cordwainers, mechanics, shopkeepers, silversmiths, and artisans.

Early agriculture within the town center quickly gave way to commerce. Benedict Arnold’s cylindrical stone mill, built in about 1670 in present-day Touro Park, is a survivor of the agricultural phase of the district’s history.

Although all of Newport’s extant 17th-century buildings were modified in later years, enough structural fabric survives to provide valuable documentation of vernacular English medieval domestic building traditions transported to the colonies and adapted to local materials and climate. At least ten 17th-century buildings remain in the district. The most notable is the Wanton-Lyman-Hazard House, built in about 1675, which continues to stand at 17 Broadway Street. It is the oldest house in Newport, and its renovation today reflects several different styles it passed through in the century after its construction.

The Friends (Quaker) Meeting House, built in 1699 in Newport, is the house of worship in Rhode Island.

Few public buildings were erected in Newport until the last two decades of the 17th century. The first Colony House was built in 1687, and eight or nine churches no longer stand. The earliest surviving public building is the simple, elongated, wood-frame Quaker Meeting House erected in 1699. Though it was later altered, it continues to stand on Marlborough Street and is Rhode Island’s only example of an early hip-roof and turreted meetinghouse. Its austerity reflects the Quaker’s belief in the “plain,” and it strongly contrasts the exuberance of the extant early 18th-century public buildings. It is the oldest house of worship in the state and is listed on the National Register of Historic Places.

At the beginning of the 18th century, Rhode Island was more concerned than any other colonies with the African slave trade, and Newport became the chief New England slave center. Many fortunes were amassed in the slave trade. Fifty or sixty Newport vessels were engaged in this traffic, and their owners were among the city’s leading merchants. By the mid-century, fine public buildings and mansions of wealthy merchants stood in the city, and row-on-row of small dwellings, many of which still stand today. Newport merchants participated in the Rhode Island plantation system outside of the city, prevalent on the island and the mainland to the west, which relied on slaves. Large country estates were established for farming, relaxation, and retirement.

During the colonial period, there were three to five times as many blacks in Rhode Island as in other New England colonies. Most who came to Newport were born in the West Indies and were often highly skilled compared with those brought directly from Africa.

Newport was the most prosperous seaport on the eastern coast and ranked among the five largest colonial port cities, with Boston, New York, Philadelphia, and Charleston. Despite war and British trade restrictions, it was a bustling port, engaged in profitable trade with the West Indies, the Atlantic seaboard towns, England, and Portugal.

The wood-framed Trinity Church was built in 1726 by local architect-builder Richard Munday and closely resembles English architecture. Located between Elm, Church, and Spring Streets, it is the second oldest parish church in the state and still has an active Episcopal congregation. Munday was also responsible for other buildings, including two Malbone houses, now gone, which were acclaimed as the most elaborate houses of their day. The simple wood-frame Sabbatarian Meeting House was built in 1729. It was later moved in 1884 and attached to the Newport Historical Society building in 1902. The prominent brick and freestone-trimmed Colony House was built between 1739 and 1741. Located at the east end of Washington Square, the colonial and state legislatures met in this well-preserved Georgian public building, the fourth-oldest statehouse in the U.S.

The Brick Market in Newport, Rhode Island, established in 1760, now serves as the Museum of Newport by Reading Tom, Flickr.

Later, Peter Harrison, one of the nation’s first and most accomplished architects, designed the Redwood Library in 1748, Touro Synagogue in 1759, and the Brick Market in 1760, all of which remain today. The Touro Synagogue, located on Touro Street, was built by the city’s Portuguese Jewish population. It is the oldest synagogue in the Western Hemisphere and is listed on the National Register of Historic Places. The Brick Market now serves as the Museum of Newport History.

By 1761, Newport had 888 dwelling houses and 439 warehouses and stores. Almost all the 120 Newport-owned vessels that sailed these routes were built in the town. Newport’s vessels carried lumber from Honduras, salt from the Mediterranean, molasses and sugar from the West Indies, hemp, fish, flour, rice, flaxseed, and whale oil.

Newport’s era of greatest prosperity was from 1740 to 1775, and many of its surviving historic structures date from these golden years. Craftsmen produced the best furniture, silver, pewter, and clocks on the East Coast during this time. At one point, the town boasted at least 99 cabinetmakers, 17 chairmakers, and two upholsterers. Artisans and artists were strongly encouraged and respected in 18th-century Newport, and their products furnished many of the city’s houses. The houses and shops of the Townsends and Goddards, whose furniture is still highly prized, are still located in the Point section near the site of former wharves with direct access to shipping for export to the West Indies and Charleston.

Newport’s tolerant religious attitudes, aggressive mercantile character, and cosmopolitan social life were disparaged as extremist and dangerous in the 17th and 18th centuries by prominent Massachusetts clergymen, London officials, and others. In reality, Newporters were political and religious moderates who pursued economic rewards and a genteel life. While some traders verged on piracy, most were commonplace but occasionally caught unaware by changing maritime restrictions, particularly with the British Navigation Acts of 1761.

In Newport, Rhode Island, the White Horse Tavern was established in 1673 and holds the oldest tavern license in the country. By

Kenneth C. Zirkel, Wikipedia

Of the many colonial taverns built during this period, the White Horse Tavern, begun in 1673, has the distinction of holding the oldest tavern license in the country. It is listed on the National Register of Historic Places. Henry Collins owned the Pitts Head Tavern.

By the mid-18th century, Newport had rebuilt itself due to its great wealth, changing from a medieval-looking town of steep-pitched roofs, turrets, and overhanging cornices to an urban center of Georgian churches, public buildings, and houses. The new or remodeled buildings were still nearly all constructed of wood, and as late as 1793, there were still only six brick structures in the town, including the Brick Market and Old State House.

Burying grounds within the district established during this period include the 17th-century Friends Cemetery at Edward and White Streets; the Clifton Burial Ground at Thomas and Golden Hill Streets, established in 1670; the Arnold Cemetery on Pelham Street, established in 1677; and the Coddington Burial Ground on Farewell Street, established between 1678 and 1700.

By the beginning of the Revolutionary War, there were 1,100 buildings, including modest seamens’, craftsmens’, and laborers’ houses, stylish merchants’ houses, commercial buildings, religious edifices, public buildings, and wharves. The buildings of this period reflect general stylistic shifts from medieval to Georgian aesthetics, the beginnings of formalized, classically derived architecture, and the use of published design sources.

This prosperous development, however, was completely undermined by the outbreak of the American Revolution. Newport’s key strategic location at the mouth of Narragansett Bay made it a prime target for the British. On December 3, 1776, the British Army under General Henry Clinton occupied Newport and retained possession until October 25, 1779. During this time, soldiers were billeted in houses and churches and scoured the town for firewood. Under the pressure of the American blockade, house after house was torn down by the British to meet the need for firewood until some 480 buildings of various kinds were destroyed. Many Newporters, loyalists, and others left, and the population dropped from 9,209 in 1774 to 5,229 by 1776. By 1784, it had declined even further to only 4,000 and continued to decrease.

American troops reoccupied Newport on October 26, 1779. The French army arrived at Newport on July 10, 1780, and remained there until June 1781. By that time, the community’s population amounted to only 1,000. Several buildings that were occupied by the French army still stand, including General Rochambeau’s headquarters at the Vernon House on Clarke Street. About 1,100 buildings stood in Newport at the beginning of the Revolutionary War. Of these, at least 300 are still standing today.

Narragansett Bay, Rhodie Island by Bob Capra, Flickr

With the coming of peace, Newport’s former trade failed to revive. Providence, located at the less vulnerable head of Narragansett Bay, had become the government center of Rhode Island during the war and now surpassed Newport in trade. Though it would be years before the community recovered, several buildings were built, including a home built for 21 ship captains on Bridge Street in 1800 and a handsome Federal-style house built by merchant Samuel Whitehorne in 1811. It is located at 414-418 Thames Street. The city’s third bank, Newport Bank, opened its doors in 1803 at the Abraham Riviera House on Washington Square, which still houses a bank today.

However, the Embargo Acts of 1807 and 1809 and the War of 1812 again checked trade, and from 1815 to 1828, Newport remained in a state of suspended animation with a stifled economy and almost no new construction. Though a few industries were established on the waterfront just outside the district, Newport had no substantial water power, little industrial tradition, and limited land to develop a strong industrial economy. As a result of the devastation and inactivity of approximately 30 years, from 1815 to 1828, Newport remained in a state of suspended animation.

Kingscote is an 1839 Gothic Revival house built by Richard Upjohn. It was the first summer residence in Newport, Rhode Island. Photo by Daniel Case, Wikipedia.

It was not until the 1830s that the city began to recover again. At that point, city residents began to focus on the resort trade. At this time, its growth as a summer resort and not as a port began. The seasonal influx of well-to-do urban families from the south and the cities of New York, Philadelphia, Boston, and Baltimore infused the town with attributes of wealth, luxurious taste, and a cosmopolitan flavor.

Some 100 buildings erected between 1784 and 1840, which are illustrative of the Federal and Greek Revival styles, have survived. Built during the Depression years, the many fine pre-Revolutionary houses largely overshadow these latter structures. The 400 historic structures are largely concentrated near the waterfront and situated within the 18th-century limits of the town. Modern structures in this area are few and do not seriously mar the general historical setting.

Newport’s population increased from 8,000 in 1840 to 20,000 in 1885, accompanied by a construction boom of summer and year-round houses. The extensive U.S. Navy presence on Goat and Coaster’s Harbor Islands also influenced Newport’s development in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. The Naval Academy had moved temporarily from Annapolis, Maryland, to Newport during the Civil War, and a naval torpedo station was established on Goat Island in 1869. The U. S. Army also maintained a presence in Newport, based at Fort Adams. For soldiers and sailors, central Newport was an off-base destination.

The decade of the 1840s coincided with the introduction of steamboat service just outside the district and later train service into the district. These transportation improvements contributed to the increased number of summer visitors and gradually also the number of day visitors.

Both train and steamboat service continued into the mid-20th century. The most visually impressive and architecturally significant products of this period are the imposing summer houses on ample grounds erected for seasonal residents outside the district to the east, south, and southwest. Yet, the historic district remained the heart and core of Newport, where churning activity supported development elsewhere. Shops, professional offices, services, banks, some government offices, and houses of worship were clustered within the old colonial town, particularly along Thames and Spring Streets and at Washington Square. Several large hotels, constructed in the 1840s but no longer extant, accommodated summer visitors.

For the most part, however, the district neighborhoods were solidly working and middle class. The smaller houses were single and multi-family, simple and sturdy, and often with minimal ornamentation.

The expansion of the population created a housing shortage for the working class in the latter half of the 19th century. Tenements, such as those constructed by William S. Cranston at 343 and 345 Spring Street, and other speculative rental properties built by local investors helped alleviate the problem. However, the congested neighborhoods of the town center had little land for new buildings.

By the third quarter of the 19th century, civic improvements were undertaken by the town and by wealthy philanthropists, including the construction of fire stations, the Cutting Memorial Chapel, and the Mary Street YMCA. The convergence of the wealthy summer residents, the military, and town needs are illustrated in the Army and Navy YMCA of 1911. Given by a noted Cincinnati philanthropist in honor of her two sons and designed by a New York architect, the large building on Washington Square was a haven for soldiers and sailors on leave. The Beaux-Arts building now serves as low-income housing and is listed on the National Register of Historic Places.

Newport’s colonial houses, considered old and unfashionable for decades, had begun to receive attention around the nation’s Centennial celebration in 1876. The rich assemblage offered numerous design sources for the emerging Colonial Revival style, and the district’s houses played a major part in its development.

Washington Square retained its key governmental role, which had diminished when City Hall was moved to Broadway, with the erection of Newport County Court House in 1926. The courthouse was the last major building erected within the district. Newport Center declined in the 1930s as the town’s economy stalled, the building boom ended, the waterfront mills closed, seaport activity halted, and the number of summer visitors dwindled.

Colony House, Newport, Rhode Island by Daniel Case, Wikipedia..

The major changes within the district in the 20th century were associated with highway projects and urban renewal from the 1950s through the 1970s and are concentrated along Thames Street and Broadway. The waterfront and wharf areas west of Thames Street and south of Marsh Street are excluded from the district due to the demolition and relocation of historic buildings, the construction of new buildings, and the construction of America’s Cup Boulevard. While the impact of these activities is undeniable, the effects are concentrated near the district’s edges, and modern intrusions within the district are few. Substantial numbers of buildings in the waterfront areas and throughout the district have been restored through the efforts of private individuals, organizations, and the city government.

Today, the Newport National Historic Landmark District is a dense, waterfront urban concentration of over 1,400 residential, commercial, institutional, and public buildings constructed between the 1670s and the early 20th century. The 1332 buildings, structures, and sites contribute to its historic and architectural significance as a colonial seaport and 19th and early 20th-century resort community. Washington Square, formerly the Mall or Parade, is the geographic and symbolic center, the heart of the early settlement, civic, and mercantile activities, and the pivotal hub linking the district’s neighborhoods.

The district’s character is that of a highly distinctive and well-preserved colonial city with an overlay of later 19th through early 20th-century development. The colonial seaport city is defined by an outstanding collection of nearly 300 surviving 17th and 18th-century buildings and an irregular grid pattern of streets established in the 18th century. The presence of several hundred 19th-century buildings attests to the city’s new era of growth as a summer resort and naval operations center from about 1840 into the early 20th century when infill construction occurred in conjunction with the erection of fashionable mansions and a major naval base outside the town center. The district contains singular examples of colonial and 19th-century public and domestic architecture representing the work of important period architects and builders, numerous exemplary high-style buildings, and, of equal importance, rows of small vernacular houses and shops. Buildings are predominantly of wood-frame construction with gable, gambrel, hip, or mansard roofs and clapboard or shingle sheathing of one to three stories in height and are set either close to or exactly at the sidewalk line on small lots. The handful of brick and stone buildings tend to be non-domestic. Various outbuildings, fences, lot landscaping treatments, walkway paving materials, and small public open spaces help complete the tight weave of texture that characterizes the streetscapes.

Colonial-era buildings along Spring Street in the Newport, Rhode Island, historic district. Image by Daniel Case, Wikipedia.

Newport is located at the southern end of Aquidneck Island, the largest island in Narragansett Bay, and sits at the entrance to the bay. It is located approximately 33 miles southeast of Providence, Rhode Island, and 20 miles south of Fall River, Massachusetts.

Newport draws thousands of visitors every year due to its history, its setting on Newport’s waterfront, and the restaurants and shops located within it along Thames Street.

More Information:

Newport Historical Society

82 Touro Street

Newport, Rhode Island 02840

401-846-0813

Compiled and edited by Kathy Alexander/Legends of America, updated February 2024.

Also See:

Sources: