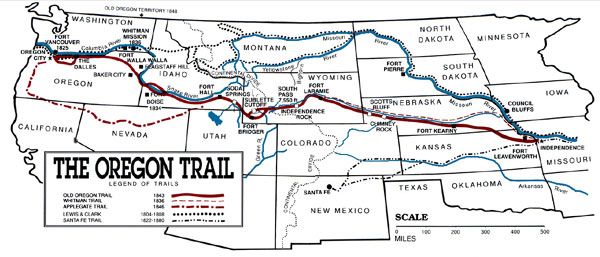

Oregon Trail Map

The Oregon Trail became one of the key migration routes that pioneers used to cross to the vast West. Spanning over half the continent, the trail proceeded 2,170 miles west through Missouri, Kansas, Nebraska, Wyoming, Idaho, and Oregon. The long journey through endless plains, rolling hills, and mountain passes began in Independence, Missouri, and ended at the Columbia River in Oregon.

Events & Stories:

The Cayuse War – Revenge for the Measles

Crime and Punishment on the Overland Trails

Danger and Hardship on the Oregon Trail

Disease and Death on the Overland Trails

A Ghost Story on the Oregon Trail

Ezra Meeker – Oregon Trail Pioneer

Oregon-California Trail Timeline

Sager Orphans on the Oregon Trail

Eye Witness Accounts:

Crossing the Great Plains in Ox-Wagons

People:

Benjamin Bonneville – Exploring & Defending the American West

Jim Bridger – Quintessential Guide of the Rocky Mountains

Ephraim Brown – Murdered on the Oregon Trail

Corps of Discovery – The Lewis & Clark Expedition

George Donner – Leading the Infamous Donner Party

John C. Fremont – The Pathfinder

Hall Jackson Kelley – Promoting the Oregon Trail

Charles Preuss – Mapping the Oregon Trail

Oregon Trail Historic Sites:

Landmarks Along the Oregon Trail

Independence, Missouri – Queen City of the Trails

Minor Park/Red Bridge Crossing – Kansas City, Missouri

Vieux Crossing, Kansas

Alcove Spring – Blue Rapids, Kansas

Rock Creek Station, Nebraska

Fort McPherson, Nebraska

Fort Kearny – Kearney, Nebraska

California Hill/Upper Crossing, Nebraska

Oregon Trail Through the Platte River Valley, Nebraska

Scotts Bluff, Nebraska

Oregon-California Trail Across Wyoming

Fort Laramie, Wyoming

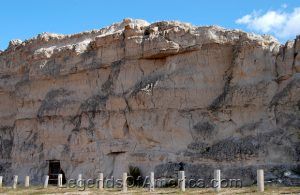

Register Cliff, Guernsey, Wyoming

Guernsey Ruts (Deep Rut Hill) – Guernsey, Wyoming

South Pass – Gateway to the West, Wyoming

South Pass City, Wyoming

Soda Springs Complex – Soda Springs, Idaho

Fort Hall, Idaho

Three Island Crossing – Glenns Ferry, Idaho

Oregon Trail Interpretive Center – Baker City, Oregon

“When you start over these wide plains, let no one leave dependent on his best friend for anything, for if you do, you will certainly have a blow-out before you get far.”

— John Shivley, 1846

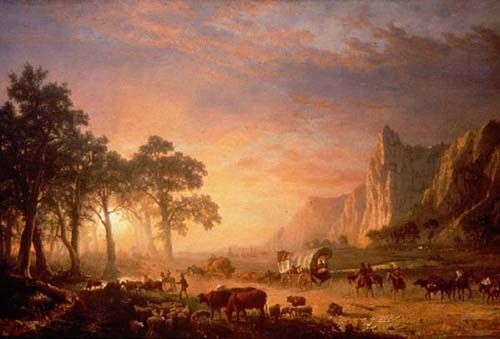

Oregon Trail, Albert Bierstadt, 1869.

Fur traders and explorers began scouting the Oregon Trail route as early as 1823. By the 1830s, it was regularly used by mountain men, traders, missionaries, and military expeditions.

At the same time, small groups of individuals and the occasional family attempted to follow the trail, with some succeeding in arriving at Fort Vancouver, Washington.

On May 16, 1842, the first organized wagon train on the Oregon Trail set out from Elm Grove, Missouri, with more than 100 pioneers. On May 22, 1843, with up to 1,000 settlers, livestock, and more, the Great Migration departed to follow the same route from Independence, Missouri, arriving in the Willamette Valley in a massive wagon train. Hundreds of thousands more would follow, especially after gold was discovered in California in 1849.

While the first few parties organized and departed from Elm Grove, Missouri, the Oregon Trail’s generally designated starting point was Independence or Westport, Missouri. The trail ended at Oregon City, Oregon, the proposed capital of the Oregon Territory at the time. However, many settlers branched off or grew exhausted short of this goal and settled at convenient or promising locations.

At many places along the trail, alternate routes called “cutoffs” were established to shorten the trail or circumvent rugged terrain. The Lander and Sublette cutoffs provided shorter routes through the mountains than the main route, bypassing Fort Bridger, Wyoming. The Salt Lake cutoff later provided a route to Salt Lake City.

The Oregon Trail was too long and arduous for the standard Conestoga wagons used in the eastern U.S. for most freight transport. These big wagons were known for killing their oxen teams approximately two-thirds along the trail and leaving their unfortunate owners stranded in the desolate, isolated territory. The only solution was to abandon all belongings and traipse onward with the supplies and tools that could be carried or dragged. In one case in 1846, the Donner Party, en route to California, was stranded in the Sierra Nevada in November and had to resort to cannibalism to survive.

This led to the rapid development of the prairie schooner. Though this wagon looked similar, it was approximately half the size of the big Conestoga wagon and manufactured in quantity by the Conestoga Brothers. It was designed for the conditions and was a marvel of engineering in its time.

Pioneers on the Oregon Trail followed various rivers and used landmarks along the trail to guide their way and gauge their progress. Within Nebraska, the Oregon Trail followed the Platte River and the North Platte River into Wyoming. Along this part of the journey, the Great Plains started giving way to bluffs and hills that were the precursor of the Rocky Mountains. After crossing the Rockies through South Pass, the trail followed the Snake River to the Columbia River. From there, emigrants could raft down the Columbia River to Fort Vancouver or take the Barlow Road to the Willamette Valley and other destinations in Washington and Oregon.

Many rock formations became famous landmarks that Oregon Trail pioneers used to navigate and leave messages for pioneers following behind them.

The pioneers’ first landmarks were in Western Nebraska, such as Court House Rock, Chimney Rock, and Scotts Bluff (where wagon ruts can still be seen today). Further west, in Wyoming, visitors can still read the names of pioneers carved into a landmark bluff called Register Cliff.

Chimney Rock in Nebraska, by Kathy Alexander. Several other trails followed the Oregon Trail for part of its length. These include the Mormon Trail from Illinois to Utah and the California Trail to the goldfields of California.

Other migration paths for early settlers before the transcontinental railroads involved taking passage on a ship rounding the Cape Horn of South America or to the Isthmus (now Panama) between North and South America. An arduous mule trek through treacherous swamps and rainforests awaited the traveler. A ship was typically then taken to San Francisco, California.

The trail was still used during the Civil War, but traffic declined after the transcontinental railroad’s completion in 1869.

However, in its more than 25 years of regular use, the trail carried an estimated 300,000 emigrants to the vast West, which took about five months to complete. The trail continued to be used into the 1890s, when modern highways began to take their place, eventually paralleling large portions of the trail. Today, U.S. Highway 26 has long followed the Oregon Trail.

Some of the original routes from our nation’s early days remain today as reminders of our historic past. The Oregon National Historic Trail is an extended trail that follows much of the original path of the Oregon Trail.

In 1968, Congress enacted the National Trails System Act, and in 1978, National Historic Trail designations were added. The National Historic Trails System commemorates these historic routes and promotes preservation, interpretation, and appreciation.

In 1995, the National Park Service established the National Trails System Office in Salt Lake City, Utah. The Salt Lake City Trails Office administers the Oregon, the California, the Mormon Pioneer Trail, and the Pony Express National Historic Trails.

The National Trails System does not manage trail resources on a day-to-day basis. The responsibility for managing trail resources remains in the hands of the current federal, state, local, and private trail managers.

National Historic Trails recognize diverse facets of history, such as significant exploration routes, migration, trade, communication, and military action. The historic trails generally consist of remnant sites and trail segments and thus are not necessarily contiguous.

Contact Information:

National Trails System Office

P.O. Box 45155

Salt Lake City, Utah 84145-0155

801- 741-1012

© Kathy Alexander/Legends of America, updated July 2024.

Also See: