Build definition

This page describes sbt build definitions, including some “theory” and

the syntax of build.sbt.

It assumes you have installed a recent version of sbt, such as sbt 0.13.13,

know how to use sbt,

and have read the previous pages in the Getting Started Guide.

This page discusses the build.sbt build definition.

Specifying the sbt version

As part of your build definition you will specify the version of

sbt that your build uses.

This allows people with different versions of the sbt launcher to

build the same projects with consistent results.

To do this, create a file named project/build.properties that specifies the sbt version as follows:

sbt.version=0.13.16

If the required version is not available locally,

the sbt launcher will download it for you.

If this file is not present, the sbt launcher will choose an arbitrary version,

which is discouraged because it makes your build non-portable.

What is a build definition?

A build definition is defined in build.sbt,

and it consists of a set of projects (of type Project).

Because the term project can be ambiguous,

we often call it a subproject in this guide.

For instance, in build.sbt you define

the subproject located in the current directory like this:

lazy val root = (project in file("."))

.settings(

name := "Hello",

scalaVersion := "2.12.2"

)

Each subproject is configured by key-value pairs.

For example, one key is name and it maps to a string value, the name of

your subproject.

The key-value pairs are listed under the .settings(...) method as follows:

lazy val root = (project in file("."))

.settings(

name := "Hello",

scalaVersion := "2.12.2"

)

How build.sbt defines settings

build.sbt defines subprojects, which holds a sequence of key-value pairs

called setting expressions using build.sbt DSL.

lazy val root = (project in file("."))

.settings(

name := "hello",

organization := "com.example",

scalaVersion := "2.12.2",

version := "0.1.0-SNAPSHOT"

)

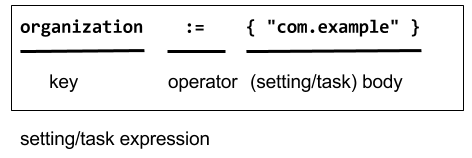

Let’s take a closer look at the build.sbt DSL:

Each entry is called a setting expression.

Some among them are also called task expressions.

We will see more on the difference later in this page.

A setting expression consists of three parts:

- Left-hand side is a key.

- Operator, which in this case is

:= - Right-hand side is called the body, or the setting body.

On the left-hand side, name, version, and scalaVersion are keys.

A key is an instance of

SettingKey[T],

TaskKey[T], or

InputKey[T] where T is the

expected value type. The kinds of key are explained below.

Because key name is typed to SettingKey[String],

the := operator on name is also typed specifically to String.

If you use the wrong value type, the build definition will not compile:

lazy val root = (project in file("."))

.settings(

name := 42 // will not compile

)

build.sbt may also be

interspersed with vals, lazy vals, and defs. Top-level objects and

classes are not allowed in build.sbt. Those should go in the project/

directory as Scala source files.

Keys

Types

There are three flavors of key:

SettingKey[T]: a key for a value computed once (the value is computed when loading the subproject, and kept around).TaskKey[T]: a key for a value, called a task, that has to be recomputed each time, potentially with side effects.InputKey[T]: a key for a task that has command line arguments as input. Check out Input Tasks for more details.

Built-in Keys

The built-in keys are just fields in an object called

Keys. A build.sbt implicitly has an

import sbt.Keys._, so sbt.Keys.name can be referred to as name.

Custom Keys

Custom keys may be defined with their respective creation methods:

settingKey, taskKey, and inputKey. Each method expects the type of the

value associated with the key as well as a description. The name of the

key is taken from the val the key is assigned to. For example, to define

a key for a new task called hello,

lazy val hello = taskKey[Unit]("An example task")

Here we have used the fact that an .sbt file can contain vals and defs

in addition to settings. All such definitions are evaluated before

settings regardless of where they are defined in the file.

Note: Typically, lazy vals are used instead of vals to avoid initialization order problems.

Task vs Setting keys

A TaskKey[T] is said to define a task. Tasks are operations such as

compile or package. They may return Unit (Unit is Scala for void), or

they may return a value related to the task, for example package is a

TaskKey[File] and its value is the jar file it creates.

Each time you start a task execution, for example by typing compile at

the interactive sbt prompt, sbt will re-run any tasks involved exactly

once.

sbt’s key-value pairs describing the subproject can keep around a fixed string value

for a setting such as name, but it has to keep around some executable

code for a task such as compile — even if that executable code

eventually returns a string, it has to be re-run every time.

A given key always refers to either a task or a plain setting. That is, “taskiness” (whether to re-run each time) is a property of the key, not the value.

Defining tasks and settings

Using :=, you can assign a value to a setting and a computation to a

task. For a setting, the value will be computed once at project load

time. For a task, the computation will be re-run each time the task is

executed.

For example, to implement the hello task from the previous section:

lazy val hello = taskKey[Unit]("An example task")

lazy val root = (project in file("."))

.settings(

hello := { println("Hello!") }

)

We already saw an example of defining settings when we defined the project’s name,

lazy val root = (project in file("."))

.settings(

name := "hello"

)

Types for tasks and settings

From a type-system perspective, the Setting created from a task key is

slightly different from the one created from a setting key.

taskKey := 42 results in a Setting[Task[T]] while settingKey := 42

results in a Setting[T]. For most purposes this makes no difference; the

task key still creates a value of type T when the task executes.

The T vs. Task[T] type difference has this implication: a setting can’t

depend on a task, because a setting is evaluated only once on project

load and is not re-run. More on this in task graph.

Keys in sbt shell

In sbt shell, you can type the name of any task to execute

that task. This is why typing compile runs the compile task. compile is

a task key.

If you type the name of a setting key rather than a task key, the value

of the setting key will be displayed. Typing a task key name executes

the task but doesn’t display the resulting value; to see a task’s

result, use show <task name> rather than plain <task name>. The

convention for keys names is to use camelCase so that the command line

name and the Scala identifiers are the same.

To learn more about any key, type inspect <keyname> at the sbt

interactive prompt. Some of the information inspect displays won’t make

sense yet, but at the top it shows you the setting’s value type and a

brief description of the setting.

Imports in build.sbt

You can place import statements at the top of build.sbt; they need not

be separated by blank lines.

There are some implied default imports, as follows:

import sbt._

import Process._

import Keys._

(In addition, if you have auto plugins, the names marked under autoImport will be imported.)

Adding library dependencies

To depend on third-party libraries, there are two options. The first is

to drop jars in lib/ (unmanaged dependencies) and the other is to add

managed dependencies, which will look like this in build.sbt:

val derby = "org.apache.derby" % "derby" % "10.4.1.3"

lazy val commonSettings = Seq(

organization := "com.example",

version := "0.1.0-SNAPSHOT",

scalaVersion := "2.12.2"

)

lazy val root = (project in file("."))

.settings(

commonSettings,

name := "Hello",

libraryDependencies += derby

)

This is how you add a managed dependency on the Apache Derby library, version 10.4.1.3.

The libraryDependencies key involves two complexities: += rather than

:=, and the % method. += appends to the key’s old value rather than

replacing it, this is explained in

Task Graph. The %

method is used to construct an Ivy module ID from strings, explained in

Library dependencies.

We’ll skip over the details of library dependencies until later in the Getting Started Guide. There’s a whole page covering it later on.