It seems the prime minister, Theresa May, and the House Speaker, John Bercow, are in resounding agreement about that part of the post-Weinstein fallout that applies to them. Any culture of sexual harassment in Westminster must be rooted out, and there must be transparency. But I have yet to hear May or Bercow acknowledge what’s working against this: a secrecy culture they have both grown up in – that of the whips’ office.

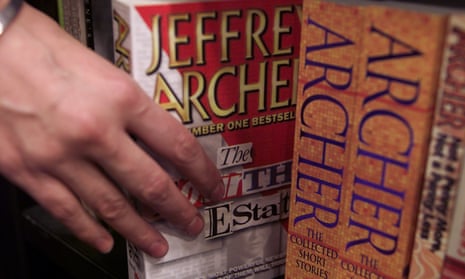

It is probably given clearest, if cartoony expression in novels such as Michael Dobbs’s House of Cards and Jeffrey Archer’s First Among Equals. For a weak government with a reduced majority, the whips are vital. And they have always made it their business to find out exactly how MPs have been misbehaving, although without caring overmuch about harassment or consent per se.

But the whole point is that they don’t challenge or blow the whistle about anything. That would be to squander important political capital. They squirrel the information away for later use. Then it’s a quiet chat over lunch at one’s club with a difficult parliamentarian, a case of: “My dear fellow, ‘blackmail’ is a ridiculous word, but things could find their way on to the front page, you know.” It’s enough to ensure some stroppy MP trudges resentfully through the correct voting lobby when the time comes. A new culture of openness at Westminster may mean a rethink of the dark arts of the whips’ office.

Vampire quids

This week the government has announced a review of “crack cocaine” betting in high-street bookmakers: the crazily addictive fixed-odds roulette terminals that allow people to burn through £300 a minute. The maximum bet could be cut to a new level, somewhere between £2 and £50.

Bookmakers themselves now have a 12-week consultation period to lobby frantically for the £50 option, which campaigners say is still ruinous. In a spirit of research, I recently went into a high-street Ladbrokes to play roulette. And, yes, it is like having the crack pipe in your hands for the first time. Each time you win, the machine makes a thrilling “zzzzhhnnnn!” sound. I was up forty quid in one minute; then I lost it all. I felt dizzy. But I quit while I wasn’t ahead. The experience formed part of a short story I have written for Radio 4 about the crack-cocaine betting phenomenon, entitled Neighbours of Zero. The moral to be drawn is probably Machiavelli’s maxim: gambling is something you encourage in your enemies’ countries.

My treat shame

Halloween was the usual disaster this year, because of a highly unfortunate personal tradition. This is my annual Display of Petulant Resentment at a Small Child’s Perceived Ingratitude. A trick-or-treater came to the door and basically reacted as if the sweet I placed into his hand was a dead rat.

“Is it a mini Milky Way?” this tiny Dracula said, with an air of distaste. “No,” I said, my voice rising to an undignified querulous pitch, “It’s A NORMAL SIZED QUALITY STREET.” After another terrible pause, he turned and left, omitting to wish me a Happy Halloween.

When I mentioned this online, the novelist Linda Grant basically sweet-shamed me, saying that giving trick-or-treaters just one sweet is entirely unacceptable. Others agreed. I was apparently very lucky indeed to escape having my entire home turned into a meringue of egg and toilet paper. There must at least two sweet-units per person, and a Haribo bag counts as one unit. Is this right? Could I please have some guidance for next year?