Gardner Pinnacles

The Gardner Pinnacles (Template:Lang-haw) are two barren rock outcrops surrounded by a reef and located in the Northwestern Hawaiian Islands.

The Pūhāhonu volcano responsible for the pinnacles is 511 nautical miles (946 km; 588 mi) northwest of Honolulu and 108 miles (94 nmi; 174 km) from French Frigate Shoals. The total area of the two small islets, remnants of an ancient shield volcano, the world's largest, is 5.939 acres (24,030 m2).[1] The highest peak is 170 feet (52 meters).[2][a] The surrounding reef has an area in excess of 1,904 square kilometres (470,000 acres; 735 sq mi).[3]

The Gardner Pinnacles were discovered and named in 1820 by the whaling ship Maro.[4] The island may be the last remnant of one of the largest volcanoes on Earth.[5] It holds the record for the largest and hottest shield volcano.[2][b]

History

The Gardner Pinnacles were first discovered on June 2, 1820, by the American whaler Maro, commanded by Captain Joseph Allen.[4]

In 1859, the position of the Gardner Pinnacles was determined by the survey schooner USS Fenimore Cooper.[6]

The Gardner Pinnacles are home to the Giant Opihi (Cellana talcosa), Hawaiian Limpet known as the ‘opihi ko‘ele, which is not found anywhere else in the world outside the Hawaiian Islands.[3] Numerous insects live on the island.[3][7]

In 1903 the Gardner Pinnacles became a part of the Hawaiian Islands Bird Reservation.[6] In 1940 it became a part of the Hawaiian Island's National Wildlife Refuge.[8] In the 21 century it is part of Papahānaumokuākea Marine National Monument wildlife refuge.[2][a]

The Gardner Pinnacles were used as an emergency helicopter landing spot for the Hawaiian HIRAN project, an effort to determine the locations of area islands with great precision for navigational purposes.[9] In the Hawaiian Archipelago, adjacent islands/reefs are French Frigate Shoals to the southeast, and Maro Reef to the northwest.

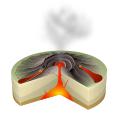

Geology

The island is made up of basalt rock,[6] which comes from lava erupted between 14 and 12 million years ago.[2][c] The rock is dark grey and dense,[6] and has a high forsterite content implying the magma source was at 1,703 ± 56 °C (3,097 ± 101 °F).[2][d]

According to a 2020 report in Earth and Planetary Science Letters, Pūhāhonu contains approximately 150,000 cubic kilometres (36,000 cu mi) of rock, based on a 2014 sonar survey.[2][e] This would make it Earth's largest single volcano. Only about one-third of that volume is exposed above the sea floor while the rest is buried beneath a ring of debris, broken coral, and other material that has eroded from the peak. By comparison, from sea floor to peak, Mauna Kea, on Hawaii's Big Island, is the tallest shield volcano on Earth, but it is nowhere near as massive as Pūhāhonu. Another volcano on the Big Island is Mauna Loa; a 2013 study estimates Mauna Loa's volume at 83,000 cubic kilometres (20,000 cu mi) which is believed to be an overestimate.[2][e] Pūhāhonu is so heavy, researchers note, that it has caused Earth's crust nearby—and thus the volcano itself—to sink hundreds of meters over millions of years.[10] The Puhahonu volcano (Gardner) would be twice as big as Mauna Loa's based on that research.[5] [f]

The Pūhāhonu and West Pūhāhonu volcanoes result from the Hawaii hotspot which is fed by the Hawaiian plume which had a major magmatic flux pulse at the time.[2][c] A longer magmatic flux pulse produced the Hawaiian Islands.[2][c] The five seamounts of the Naifeh Chain to the north of Pūhāhonu have a completely different tectonic origin, and are older (Late Cretaceous).[12] At one time they were hypothesised to be related to the Pūhāhonu volcano because of arch volcanism, which can not be the case, given the newly determined age difference.[12]

Ecology

The island has one plant known to grow on it, the succulent sea purslane.[13] However, there are over a dozen species of bird observed here, many nesting.[13] There is also a variety of insect species on the island.[13]

In the surrounding waters there is variety of sealife, which is noted as habitat for a limpet, the giant ophi which lives in tidal areas of the rocky island.[13] There are many species of fish and coral life in the nearby waters.[13]

The large numbers of birds have coated many surfaces of the island in guano, giving it a whitish appearance.[6]

Some of the fish species in the nearby waters include red lip parrotfish, doublebar goatfish, and reef triggerfish.[14]

Name

The name Gardner comes from its discovery in 1820, when the Captain Joseph Allen of the ship Maro named it Gardner's Island.[13] They also discovered Maro Reef, which is named for that sailing ship.[15]

It has sometimes been called Gardner Rock or Gardner Island, besides the Gardner Pinnacles.[16]

The Hawaiian name, Pūhāhonu, means 'turtle surfacing for air', from pūhā 'to breathe at the surface' and honu 'turtle'.[17]

See also

- List of volcanoes in the Hawaiian – Emperor seamount chain

- Nikumaroro (aka Gardner Island)

Notes

- ^ a b Garcia et. al. 2020: 1. Introduction

- ^ Garcia et. al. 2020: Abstract

- ^ a b c Garcia et. al. 2020: Conclusion

- ^ Garcia et. al. 2020: 4.3. What caused Pūhāhonu's large volume?

- ^ a b Garcia et. al. 2020: 4.2. How massive is Pūhāhonu?

- ^ The Tamu Massif, a 4-kilometer-tall volcanic feature the size of the British Isles on the sea floor east of Japan, contains almost 7 million cubic kilometers of material and was once thought to be the world's largest shield volcano. But Tamu Massif is now believed to have formed along a mid-ocean ridge rather than over a single source of magma. That makes Pūhāhonu the largest known shield volcano on Earth.[11]

References

- ^ Giuliani-Hoffman, Francesca. "The largest volcano in the world sits beneath two small rocky peaks in Hawaii". CNN. Retrieved May 26, 2020.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Garcia, Michael O.; Tree, Jonathan P.; Wessel, Paul; Smith, John R. (July 15, 2020). "Pūhāhonu: Earth's biggest and hottest shield volcano". Earth and Planetary Science Letters. 542: 116296. doi:10.1016/j.epsl.2020.116296. ISSN 0012-821X.

- ^ a b c Gardner Pinnacles - Hawaiian Islands National Wildlife Refuge. U.S Fish and Wildlife Service. December 14, 2016

- ^ a b Mark J. Rauzon (2001). Isles of Refuge: Wildlife and History of the Northwestern Hawaiian Islands. University of Hawaii Press. pp. 95–. ISBN 978-0-8248-2330-6.

- ^ a b "SOEST researchers reveal largest and hottest shield volcano on Earth".

- ^ a b c d e Clapp, Roger B. (1972). "The natural history of Gardner Pinnacles, Northwestern Hawaiian Islands". Atoll Research Bulletin. 163. Smithsonian Institution: 1–25. doi:10.5479/si.00775630.163.1. ISSN 0077-5630. OCLC 887851.

- ^ Gardner Pinnacles (Pūhāhonu) Papahānaumokuākea (Northwestern Hawaiian Islands) Marine National Monument

- ^ "RogerClapp.pdf".

- ^ King, Warren B. (March 1973). "Conservation Status of Birds of Central Pacific Islands". The Wilson Bulletin. 85 (1). Wilson Ornithological Society: 89–103. JSTOR 4160286.

- ^ Perkins, Sid (May 12, 2020). "World's biggest volcano is barely visible". www.science.org. Retrieved May 5, 2022.

- ^ World’s biggest volcano is barely visible, Science Magazine, May. 12, 2020. doi:10.1126/science.abc7615

- ^ a b Sotomayor, A; Balbas, A; Konrad, K; Koppers, AA; Konter, JG; Wanless, VD; Hourigan, TF; Kelley, C; Raineault, N (2023). "New insights into the age and origin of two small Cretaceous seamount chains proximal to the Northwestern Hawaiian Ridge". Geosphere. 19 (2): 383–405. doi:10.1130/GES02580.1.

- ^ a b c d e f "Papahanaumokuakea Marine National Monument". www.papahanaumokuakea.gov.

- ^ "Gardner Pinnacles - Hawaiian Islands - U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service".

- ^ "Papahanaumokuakea Marine National Monument". www.papahanaumokuakea.gov.

- ^ "Log of the Kaalokai". 1909.

- ^ "Nā Puke Wehewehe ʻŌlelo Hawaiʻi". wehewehe.org.