Books by David Rose

Oxford University Press, 2006

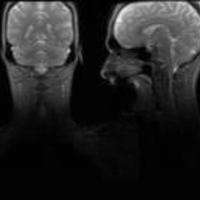

What makes us conscious - of our self, our surroundings, and our place in those surroundings? Wha... more What makes us conscious - of our self, our surroundings, and our place in those surroundings? What neural processes drive our awareness, and how do these processes relate to what we think of as our mind? This book seeks to respond to some of these questions, offering a wealth of information from which the reader can develop their own views of the subject. Taking a critical, thought-provoking approach, the book integrates studies from philosophy, psychology, and neuroscience to capture the major themes on which our current understanding of consciousness is based. Opening with a series of chapters that introduce us to thinking about mind, the book goes on to explore function and brain, examining such topics as functionalism, representation, and brain dynamics. Understanding consciousness remains one of today's greatest challenges.

Baifukan, Tokyo, 2008

Translation into Japanese by N. Osaka of "Consciousness: Philosophical, Psychological and Neural ... more Translation into Japanese by N. Osaka of "Consciousness: Philosophical, Psychological and Neural Theories" (2006).

Oxford University Press, 1995

In the words of Richard Gregory `Here are to be found novel links to art and science, and to mind... more In the words of Richard Gregory `Here are to be found novel links to art and science, and to mind and brain... These many themes are captured to weave a tapestry of the intelligent brain behind the artful eye.'

This fascinating volume presents the thoughts of scientists and artists working on many aspects of visual perception, ranging from the physiology of the brain, development of sight in infants, and the significance of faces, to the physics of images and the mathematics of impossible objects. There are essays on perspective, especially of Vermeer's use of the camera oscura, alongside an examination of the art of the forger, portraits of artists and scientists, and a personal statement by the late sculptress, Dame Elisabeth Frink.

Complete with over 200 illustrations, including colour plates by Hockney, Magritte, Vermeer, and others, this is a an enlightening mixture of biology and aesthetics which will appeal to psychologists, vision scientists, and all those interested in the effect of the visual arts on the eye and brain.

Wiley, 1985

A comprehensive and thought-provoking book which presents the views of 71 leading theorists on th... more A comprehensive and thought-provoking book which presents the views of 71 leading theorists on the underlying mechanisms and functions of the primary visual cortex. Current methodological strategies for model building and assessment, suitable for dealing with relatively simple physical systems, appear inadequate to cope with the more complex, self- organising, goal-directed systems studied in the behavioural and brain sciences. This book does not attempt to converge onto a singular 'correct' model of the visual cortex, but rather to reflect the importance of differences in researchers' ideas and preconceptions about the overall function of the visual system, as well as deeper issues about scientific goals and methods. The chapters are placed in approximate (but by no means monotonic) order of level of description, starting with overall function and running through to the detailed microanatomy. The final chapters suggesting directions for future research place in context a fascinating area of study which will continue to interest psychologists, physiologists, anatomists, neuroscientists, cyberneticians and researchers in artificial intelligence for many years to come.

Journal articles by David Rose

Perception, 2022

First, I agree with Cheng that the argument from illusions to indirect realism is controversial, ... more First, I agree with Cheng that the argument from illusions to indirect realism is controversial, especially as to what is meant by “realism,” “veridical,” and “sense data” and the background assumptions underlying them. I provide a finer specification of some of the sub-movements that were the specific concerns of my previous article, particularly phenomenology as it currently sees itself in perception research, and the relevance of illusions. Perception has turned out to be far more complex than traditional philosophy realized, as has been revealed by recent research in neuroscience and psychophysics. Lastly, I answer Cheng’s question about the “causal exclusion argument” by suggesting it is obviated by the temporal substructure of metaphysical states, and I provide a detailed supporting case in Supplementary Material.

Perception, 2022

Illusions are commonly defined as departures of our percepts from the veridical representation of... more Illusions are commonly defined as departures of our percepts from the veridical representation of objective, common-sense reality. However, it has been claimed recently that this definition lacks validity, for example, on the grounds that external reality cannot possibly be represented truly by our sensory systems, and indeed may even be a fiction. Here, I first demonstrate how novelist George Orwell warned that such denials of objective reality are dangerous mistakes, in that they can lead to the suppression and even the atrophy of independent thought and critical evaluation. Second, some anti-realists assume their opponents hold a fully reductionist metaphysics, in which fundamental physics describes the only ground truth, thereby placing it beyond direct human sensory observation. In contrast, I point to a more recent and commonly used alternative, non-reductive metaphysics. This ascribes real existence to many levels of dynamic systems of information, emerging progressively from the subatomic to the biological, psychological, social, and ecological. Within such a worldview the notion of objective reality is valid, it comes in part within the range of our senses, and thus a definition of illusions as kinds of deviations from veridical perception becomes possible again.

Perception, 2019

The famous ‘man in the head’ fallacy arises from the idea that the visual system projects an imag... more The famous ‘man in the head’ fallacy arises from the idea that the visual system projects an image of the outside world onto a (virtual) inner screen or stage which our consciousness then inspects – as though each consciousness is a little person, with its own eyes, located inside the head. However, this doesn’t actually explain how vision works – it just postpones the problem. How does the man in the head’s visual perception work – by the same principle? We would have an infinite regress of ‘explanations’, which will never reach a conclusion.

But does it solve anything to replace the man in the head with a ‘painter n the head’? Recent writers have suggested that all visual experience is a form of hallucination or dream, of ‘mental paint’, generated within the mind and, as it were, projected onto a phenomenal field – a virtual or functional internal screen ‘depicting’ an (apparent) outside world. But isn’t this too a fallacious explanation? Who decides what to paint, or why, or how? Inside the painter there must be yet another homunculus with the abilities of a complete mind – a mind within a mind – and so on, leading us to an infinite regress of explanations here also.

Both fallacies thus arise through their common, more fundamental assumption of a dualist mind. This may have led some phenomenologists and vision scientists to converge onto superficially different but similarly inadequate theories.

i-Perception, 2018

Towards the end of the 19th Century, Hering and Helmholtz were arguing about the fineness of visu... more Towards the end of the 19th Century, Hering and Helmholtz were arguing about the fineness of visual acuity. In a talk given in 1899, Hering finally established beyond reasonable doubt that humans can see spatial displacements smaller than the diameter of a foveal cone receptor, an ability we nowadays call 'hyperacuity' and still the topic of active research. Hering suggested that this ability is made manifest by averaging across the range of locations stimulated during miniature eye movements. However, this idea was made most clear only in a footnote to this (not well known) publication of his talk and so was missed by many subsequent workers. Accordingly, particularly towards the end of the 20th Century, Hering has commonly been mis-cited as having proposed in this paper that averaging occurs purely along the lengths of the edges in the image. Here, we present in translation what Hering actually said and why. In Supplementary Material, we additionally translate accounts of some background experiments by Volkmann (1863) that were cited by Hering.

i-Perception, 2018

Alfred Wilhelm Volkmann (1801–1877) was a German physiologist, anatomist, and

philosopher who wo... more Alfred Wilhelm Volkmann (1801–1877) was a German physiologist, anatomist, and

philosopher who worked in Leipzig, Dorpat (currently, Tartu, Estonia) and Halle. He

performed original research on a range of topics including neuroanatomy and optics (e.g.

1836, 1846, 1863) which was frequently cited by Helmholtz (1867). In his 1863 book he

reported extensive psychophysical studies on visual acuity.

In the following we translate accounts of some background experiments by Volkmann that were cited by Hering (1899), particularly those relevant to what is now called hyperacuity, and to the concept of just unnoticeable differences.

Neuropsychological Rehabilitation, 2018

Acquired brain injury (ABI) has a negative impact on self-esteem, which is in turn associated wit... more Acquired brain injury (ABI) has a negative impact on self-esteem, which is in turn associated with mood disorders, maladaptive coping and reduced community participation. The aim of the current research was to explore self-esteem as a multi- dimensional construct and identify which factors are associated with symptoms of anxiety or depression. Eighty adults with ABI aged 17–56 years completed the Robson Self-Esteem Scale (RSES), of whom 65 also completed the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale; 57.5% of the sample had clinically low self-esteem. The RSES had good internal consistency (α=.89), and factor analysis identified four factors, which differed from those found previously in other populations. Multiple regression analysis revealed anxiety was differentially predicted by “Self-Worth” and “Self-Efficacy”, R^2=.44, F(4, 58)=9, p<.001, and depression by “Self-Regard”, R^2 = .38, F(4, 58) = 9, p < .001. A fourth factor, “Confidence”, did not predict depression or anxiety. In conclusion, the RSES is a reliable measure of self-esteem after ABI. Self-esteem after ABI is multidimensional and differs in structure from self- esteem in the general population. A multidimensional model of self-esteem may be helpful in development of transdiagnostic cognitive behavioural accounts of adjustment.

Perception, 2015

Koenderink (2014, Perception, 43, 1–6) has said most Perception readers are deluded, because they... more Koenderink (2014, Perception, 43, 1–6) has said most Perception readers are deluded, because they believe an ‘All Seeing Eye’ observes an objective reality. We trace the source of Koenderink's assertion to his metaphysical idealism, and point to two major weaknesses in his position—namely, its dualism and foundationalism. We counter with arguments from modern philosophy of science for the existence of an objective material reality, contrast Koenderink's enactivism to his idealism, and point to ways in which phenomenology and cognitive science are complementary and not mutually exclusive.

Gestalt Theory, 2012

To understand the meaning of ‘meaning’ and whether the concept can be applied at sub-personal lev... more To understand the meaning of ‘meaning’ and whether the concept can be applied at sub-personal levels, its nature must first be elucidated. Full understanding of psychosemantics requires a three-dimensional state-space of possible explanations, with axes (1) atomism- holism, (2) synchronic-diachronic functionality, and (3) level of analysis. Atomism proposes that meaning depends on causal links with the world, whereas under holism, meaning is relative to the current context or system of representations. These can be combined in a hybrid atomist-holist theory which contains elements of both. To solve the problems of mis-representation however the second dimension is needed. Diachronic teleofunctionalism links meaning to what has worked in the past, and synchronic functionalism to what works in the current system or context. Which is more relevant depends on which question you ask: evolution and ontogeny can tell you a mechanism’s activity is supposed to mean for example ‘bug’, while w...

Physics of Life Reviews, 2012

Feinberg (Physics of Life Reviews 2012) has proposed that consciousness arises when high levels o... more Feinberg (Physics of Life Reviews 2012) has proposed that consciousness arises when high levels of the brain are activated. Here, I distinguish between levels of processing and of organization, arguing that consciousness emerges when feedback loops create iterative interactions between anatomical locations that are at different levels of (serial) processing, so as to form higher levels of organization. These gestalt-like emergent systems constrain their lower level constituents rather than exerting top-down causative control.

NeuroRehabilitation, 2009

Following brain injury there is often a prolonged period of deteriorating psychological condition... more Following brain injury there is often a prolonged period of deteriorating psychological condition, despite neurological stability or improvement. This is presumably consequent to the remission of anosognosia and the realisation of permanently worsened status. This change is hypothesised to be directed partially by the socially mediated processes which play a role in generating self-awareness and which here direct the reconstruction of the self as a permanently injured person. However, before we can understand this process of redevelopment, we need an unbiassed technique to monitor self-awareness.

Semi-structured interviews were conducted with 30 individuals with long-standing brain injuries to capture their spontaneous complaints and their level of insight into the implications of their difficulties. The focus was on what the participants said in their own words, and the extent to which self-knowledge of difficulties was spontaneously salient to the participants. Their responses were subjected to content analysis. Most participants were able to say that they had brain injuries and physical difficulties, many mentioned memory and attentional problems and a few made references to a variety of emotional disturbances.

Content analysis of data from unbiassed interviews can reveal the extent to which people with brain injuries know about their difficulties. Social constructionist accounts of self-awareness and recovery are supported.

Perception, 2009

Biological motion stimuli contain a great deal of information about the person and action depicte... more Biological motion stimuli contain a great deal of information about the person and action depicted. Here, we extend the known range by showing that viewers can see which member of a pair of conversing actors is talking. Moreover, the ability varies with the emotional content of the conversation. The implications for social cognitive neuroscience are discussed.

Vision Research, 2006

Binocular disparity and motion parallax provide information about the spatial structure and layou... more Binocular disparity and motion parallax provide information about the spatial structure and layout of the world. Descriptive similarities between the two cues have often been noted which have been taken as evidence of a close relationship between them. Here, we report two experiments which investigate the effect of surface orientation and modulation frequency on (i) a threshold detection task and (ii) a supra-threshold depth-matching task using sinusoidally corrugated surfaces defined by binocular disparity or motion parallax. For low frequency corrugations, an orientation anisotropy was observed in both domains, with sensitivity decreasing as surface orientation was varied from horizontal to vertical. In the depth-matching task, for surfaces defined by binocular disparity the greatest depth was seen for oblique orientations. For surfaces defined by motion parallax, perceived depth was found to increase as surface orientation was varied from horizontal to vertical. In neither case was perceived depth for supra-threshold surfaces related to threshold performance in any simple manner. These results reveal clear differences between the perception of depth from binocular disparity or motion parallax, and between perception at threshold and supra-threshold levels of performance.

Brain Injury, 2006

Background: One basic problem found during rehabilitation is that people with brain injuries lack... more Background: One basic problem found during rehabilitation is that people with brain injuries lack awareness of their difficulties. Research into this phenomenon has often disregarded the voices of those affected by the trauma and do not give an insider’s perspective on the process through which a person with a brain injury develops awareness of their difficulties. Objective: To explore how people construct their experiences of brain injury and the challenges they face afterwards. Setting: Two day care centres.

Method: In-depth interviews were conducted with 24 individuals with brain injuries. Data were analysed using the interpretative phenomenological approach (IPA).

Results: Three themes were found to be relevant for understanding how participants construct their experiences of brain injury: finding the bits of the puzzle, filling the holes of memory and redefining the self. The evidence suggests that they construct knowledge of their difficulties in a manner resembling the sorting of a puzzle.

Conclusion: Qualitative enquiries into awareness of difficulties provide clinical and rehabilitation settings with new insights and alternative strategies for interventions.

Journal of Clinical and Experimental Neuropsychology, 2005

The superiority of the modified 16-item Rey memory test over the original 15-item test has yet to... more The superiority of the modified 16-item Rey memory test over the original 15-item test has yet to be established in relation to the detection of feigned memory deficits. This study compares the effectiveness of these two versions of the test in combination with a standard memory test. Sixty-four participants, equally divided into “controls” and “simulators”, and 32 “memory-impaired” volunteers completed the WAIS-III Digit Span test and either the 15-item or 16-item Rey test. The median scores of the simula- tors were worse than those of both the controls and the memory-impaired subjects on two types of score on the 16-item test compared to just one on the 15-item test. How- ever, combining the total score from the 16-item test with the digits forward span accu- rately detected 63% of simulators (with only 6% of nonsimulators wrongly classified as simulators). This performance was better than that obtained from any of the test scores taken singly or from any other combination of a digit span score with a Rey score. It is concluded that the addition of a standard memory test to the Rey memory test improves the detection of individuals feigning memory impairment.

Perception, 2005

We examined whether it is possible to identify the emotional content of behaviour from point-ligh... more We examined whether it is possible to identify the emotional content of behaviour from point-light displays where pairs of actors are engaged in interpersonal communication. These actors displayed a series of emotions, which included sadness, anger, joy, disgust, fear, and romantic love. In experiment 1, subjects viewed brief clips of these point-light displays presented the right way up and upside down. In experiment 2, the importance of the interaction between the two figures in the recognition of emotion was examined. Subjects were shown upright versions of (i) the original pairs (dyads), (ii) a single actor (monad), and (iii) a dyad comprising a single actor and his/her mirror image (reflected dyad). In each experiment, the subjects rated the emotional content of the displays by moving a slider along a horizontal scale. All of the emotions received a rating for every clip. In experiment 1, when the displays were upright, the correct emotions were identified in each case except disgust; but, when the displays were inverted, performance was significantly diminished for some emotions. In experiment 2, the recognition of love and joy was impaired by the absence of the acting partner, and the recognition of sadness, joy, and fear was impaired in the non-veridical (mirror image) displays. These findings both support and extend previous research by showing that biological motion is sufficient for the perception of emotion, although inversion affects perfor- mance. Moreover, emotion perception from biological motion can be affected by the veridical or non-veridical social context within the displays.

Perception, 2003

The locations of visual objects and events in the world are represented in a number of different ... more The locations of visual objects and events in the world are represented in a number of different coordinate frameworks. For example, a visual transient is known to attract (exogenous) attention and facilitate performance within an egocentric framework. However, when attention is allocated voluntarily to a particular visual feature (ie endogenous attention), the location of that feature appears to be variously encoded either within an allocentric framework or in a spatially invariant manner. In three experiments we investigated the importance of location for the allocation of endogenous attention and whether egocentric and/or allocentric spatial frameworks are involved. Primes and targets were presented in four conditions designed to vary systematically their spatial relationships in egocentric and allocentric coordinates. A reliable effect of egocentric priming was found in all three experiments, which suggests that endogenous shifts of attention towards targets defined by a particular feature operate in an egocentric representation of visual space. In addition, allocentric priming was also found for targets primed by their colour or shape. This suggests that attending to targets primed by nonspatial attributes results in facilitation that is localised in more than one coordinate frame of spatial reference.

Uploads

Books by David Rose

This fascinating volume presents the thoughts of scientists and artists working on many aspects of visual perception, ranging from the physiology of the brain, development of sight in infants, and the significance of faces, to the physics of images and the mathematics of impossible objects. There are essays on perspective, especially of Vermeer's use of the camera oscura, alongside an examination of the art of the forger, portraits of artists and scientists, and a personal statement by the late sculptress, Dame Elisabeth Frink.

Complete with over 200 illustrations, including colour plates by Hockney, Magritte, Vermeer, and others, this is a an enlightening mixture of biology and aesthetics which will appeal to psychologists, vision scientists, and all those interested in the effect of the visual arts on the eye and brain.

Journal articles by David Rose

But does it solve anything to replace the man in the head with a ‘painter n the head’? Recent writers have suggested that all visual experience is a form of hallucination or dream, of ‘mental paint’, generated within the mind and, as it were, projected onto a phenomenal field – a virtual or functional internal screen ‘depicting’ an (apparent) outside world. But isn’t this too a fallacious explanation? Who decides what to paint, or why, or how? Inside the painter there must be yet another homunculus with the abilities of a complete mind – a mind within a mind – and so on, leading us to an infinite regress of explanations here also.

Both fallacies thus arise through their common, more fundamental assumption of a dualist mind. This may have led some phenomenologists and vision scientists to converge onto superficially different but similarly inadequate theories.

philosopher who worked in Leipzig, Dorpat (currently, Tartu, Estonia) and Halle. He

performed original research on a range of topics including neuroanatomy and optics (e.g.

1836, 1846, 1863) which was frequently cited by Helmholtz (1867). In his 1863 book he

reported extensive psychophysical studies on visual acuity.

In the following we translate accounts of some background experiments by Volkmann that were cited by Hering (1899), particularly those relevant to what is now called hyperacuity, and to the concept of just unnoticeable differences.

Semi-structured interviews were conducted with 30 individuals with long-standing brain injuries to capture their spontaneous complaints and their level of insight into the implications of their difficulties. The focus was on what the participants said in their own words, and the extent to which self-knowledge of difficulties was spontaneously salient to the participants. Their responses were subjected to content analysis. Most participants were able to say that they had brain injuries and physical difficulties, many mentioned memory and attentional problems and a few made references to a variety of emotional disturbances.

Content analysis of data from unbiassed interviews can reveal the extent to which people with brain injuries know about their difficulties. Social constructionist accounts of self-awareness and recovery are supported.

Method: In-depth interviews were conducted with 24 individuals with brain injuries. Data were analysed using the interpretative phenomenological approach (IPA).

Results: Three themes were found to be relevant for understanding how participants construct their experiences of brain injury: finding the bits of the puzzle, filling the holes of memory and redefining the self. The evidence suggests that they construct knowledge of their difficulties in a manner resembling the sorting of a puzzle.

Conclusion: Qualitative enquiries into awareness of difficulties provide clinical and rehabilitation settings with new insights and alternative strategies for interventions.

This fascinating volume presents the thoughts of scientists and artists working on many aspects of visual perception, ranging from the physiology of the brain, development of sight in infants, and the significance of faces, to the physics of images and the mathematics of impossible objects. There are essays on perspective, especially of Vermeer's use of the camera oscura, alongside an examination of the art of the forger, portraits of artists and scientists, and a personal statement by the late sculptress, Dame Elisabeth Frink.

Complete with over 200 illustrations, including colour plates by Hockney, Magritte, Vermeer, and others, this is a an enlightening mixture of biology and aesthetics which will appeal to psychologists, vision scientists, and all those interested in the effect of the visual arts on the eye and brain.

But does it solve anything to replace the man in the head with a ‘painter n the head’? Recent writers have suggested that all visual experience is a form of hallucination or dream, of ‘mental paint’, generated within the mind and, as it were, projected onto a phenomenal field – a virtual or functional internal screen ‘depicting’ an (apparent) outside world. But isn’t this too a fallacious explanation? Who decides what to paint, or why, or how? Inside the painter there must be yet another homunculus with the abilities of a complete mind – a mind within a mind – and so on, leading us to an infinite regress of explanations here also.

Both fallacies thus arise through their common, more fundamental assumption of a dualist mind. This may have led some phenomenologists and vision scientists to converge onto superficially different but similarly inadequate theories.

philosopher who worked in Leipzig, Dorpat (currently, Tartu, Estonia) and Halle. He

performed original research on a range of topics including neuroanatomy and optics (e.g.

1836, 1846, 1863) which was frequently cited by Helmholtz (1867). In his 1863 book he

reported extensive psychophysical studies on visual acuity.

In the following we translate accounts of some background experiments by Volkmann that were cited by Hering (1899), particularly those relevant to what is now called hyperacuity, and to the concept of just unnoticeable differences.

Semi-structured interviews were conducted with 30 individuals with long-standing brain injuries to capture their spontaneous complaints and their level of insight into the implications of their difficulties. The focus was on what the participants said in their own words, and the extent to which self-knowledge of difficulties was spontaneously salient to the participants. Their responses were subjected to content analysis. Most participants were able to say that they had brain injuries and physical difficulties, many mentioned memory and attentional problems and a few made references to a variety of emotional disturbances.

Content analysis of data from unbiassed interviews can reveal the extent to which people with brain injuries know about their difficulties. Social constructionist accounts of self-awareness and recovery are supported.

Method: In-depth interviews were conducted with 24 individuals with brain injuries. Data were analysed using the interpretative phenomenological approach (IPA).

Results: Three themes were found to be relevant for understanding how participants construct their experiences of brain injury: finding the bits of the puzzle, filling the holes of memory and redefining the self. The evidence suggests that they construct knowledge of their difficulties in a manner resembling the sorting of a puzzle.

Conclusion: Qualitative enquiries into awareness of difficulties provide clinical and rehabilitation settings with new insights and alternative strategies for interventions.

Method: A sample of adults with ABI referred for assessment for comprehensive intensive rehabilitation (N=80) completed the Robson Self-Concept Questionnaire (RSCQ) and the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale. Correlation and factor analyses were conducted to address study aims.

Results: 28% of the sample had low self-esteem and this was associated with severity of ABI (lower self-esteem in mild-to-moderate ABI than in severe ABI), depression and anxiety. Internal consistency of the RSCQ was good. Factor analysis found four dimensions of self-esteem after ABI labelled ‘self-and-existence’, ‘self-regard’, ‘self-efficacy’ and ‘confidence’. This result differed from the factor solution identified in non-ABI analysis of the measure.

Conclusions: The results suggest that the RSCQ is a reliable measure of self-esteem after ABI enabling evaluation of multiple dimensions of self-esteem. A multidimensional view of self-esteem after ABI was supported although dimensions differed from those previously identified. Consistent with an established cognitive behavioural model, self-esteem was associated with depression and anxiety, warranting further research on interventions to improve self-esteem as a means of improving emotional outcomes post ABI.

I will argue that the logical interpretation of this paradox is correct, within its own terms, but the fact that the paradox continues to be presented, discussed and reinterpreted in the philosophical literature demonstrates the continuing and unavoidable influence of psychologism. I here point to an analogy between the structure of the raven paradox and a well-studied paradox in the psychology of reasoning: Wason’s four-card selection task. This analogy enables us to apply psychological knowledge to Hempel’s paradox, and thus to throw some light on its origins. Even the best logic has to be filtered through the human mind.