14TH CENTURY SINGAPORE:

THE TEMASEK PARADIGM

LIM TSE SIANG

(B.A. HONS., NUS)

A THESIS SUBMITTED FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS

DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY

NATIONAL UNIVERSITY OF SINGAPORE

2012

��ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This thesis is not just the fruit of one’s labour, but that of many whose help I am grateful

to have received. I would like to thank first and foremost everyone in the Department of History,

my alma mater, for their willingness in accepting me as a graduate student, generosity in

granting me a research scholarship, understanding in my decision to switch from a history to a

historical-archaeology thesis-topic as well as kindness in supporting my request for a tuition

fee waiver at the end of the scholarship. It is under the aegis of this department that I have been

able to continue my wilful passion for history and often reckless endeavours in archaeology.

I owe my greatest debt to my supervisors – Dr. Mark V. Emmanuel, Associate

Professor John Norman Miksic and Associate Professor Peter Borschberg – for the successful

completion of my thesis and candidature in the M.A. programme. Both Dr. Emmanuel and

Professor Borschberg have graciously taken me under their wings despite the fact that my

research falls outside their respective interests and specializations. They have never ceased to

extend their patience and support despite my encountering of countless setbacks and failures in

the course of my work. It is their professionalism as supervisors and scholars to which I look

up and seek to emulate during my candidature. The same can no less be said of Professor Miksic,

undoubtedly one of the greatest archaeologists of Southeast Asia, whose contributions to the

i

�understanding of pre-colonial Singapore inspired this thesis in the first place. I am extremely

grateful for this privileged opportunity to learn from the breadth of his knowledge and depth of

his wisdom; it is an experience and honour which I will forever cherish.

I wish to thank in particular my mentor and friend, Associate Professor Bruce Lockhart,

for his personal guidance throughout my entire candidature. His unwavering and selfless

support helped me overcome many bouts of uncertainty and doubts, whereas his strictness and

impartiality kept me on the right track in my work. I will remember these lessons well as I move

on towards the next stage in life.

Several other scholars and individuals have also been the guiding beacons in my foray

through the challenging path of an academic life. Their influence and support is invaluable for

the completion of this thesis. I wish to thank Professor Merle Calvin Ricklefs for his instruction

on academic rigour and thoroughness in research; Associate Professor Maurizio Peleggi for his

enlightening lessons on critical analysis, subject-matter appreciation as well as sophistication

and flair in one’s work; Associate Professor Huang Jianli for his keen interest, advice and

encouraging words; Dr. Quek Ser Hwee, Dr. Sai Siew Min and Dr. Loh Kah Seng for their

support and care whilst in their service as a tutor; Mr. Kwa Chong Guan and Dr. Derek Heng

Thiam Soon for their time in advising an inexperienced and naïve graduate student; Dr. Goh

Geok Yian and Mr. Lim Chen Sian for the opportunities to study the artefacts stored at No. 6

Kent Ridge Road and participate in various excavations in Singapore; Carrick Ang for his

humour and help in digitalizing the soil profiles for posterity; and not least my senior-inarchaeology Xin Guang Can and volunteer Aoki Ryoko for their assistance and company in

laboratorial analysis as well as patience with my temperaments and antics.

Finally, I wish to thank Peter, Sally, Chris, Tim and my wife, Cherylyn, of the Wong

family in Brisbane for their welcome, kindness and love over the past year, as well as my

parents in Singapore for their trust and indulgence of freedom to pursue my interests.

Any success in this thesis is attributed to all mentioned; any fault is mine alone.

ii

�TABLE OF CONTENTS

Acknowledgements

……………………………………………………...i

Table of Contents

…………………………………………………….iii

Summary

……………………………………………………………...iv

Abbreviations ………………………………………………………………v

List of Tables ……………………………………………………………viii

List of Figures ……………………………………………………………...ix

I.

Introduction

………....……………………………………………………1

II. Temasek-Singapura:

The Paradigm and its Sources

III. Artefact Society

IV. Conclusion

……………………………………………22

…………………………………………………….51

……………………………………………………………116

Bibliography ……………………………………………………………120

Glossary

……………………………………………………………150

Appendices

A. STA Artefact Samples:

Analyses and Deductions

…………………………………………..153

B. STA Soil Stratigraphic Profiles:

Sampled Excavation Units

…………………………………………..209

C. STA Raw Artefact Data:

Pre-colonial Samples …………………………………………………...251

iii

�SUMMARY

Over two centuries have passed since the revelation of the existence of an ancient

settlement in Singapore, but knowledge of this pre-colonial polity has not advanced much with

time. Despite the archaeological recovery of material cultural remains of this settlement in

recent years, historical discourse on the subject remains largely confined to either the

epistemological significance of this settlement in the colonial and post-colonial histories of the

Malay-speaking people in the Malay Archipelago, or the general importance of this landmark

within the context of maritime trade in Southeast Asia. More often than not, artefacts are used

only to highlight these narratives but are themselves seldom addressed.

This thesis is hence dedicated to the study of these artefacts as primary sources of 14th

century Singapore. It seeks to address a fundamental question which underlies all narratives of

the settlement but has hitherto been inadequately addressed by conjunctures and hypotheses:

How complex was this pre-colonial Singapore society? In doing so, this thesis will first address

the historiographical issues underlying this question by reviewing existing literature and

primary sources concerning this pre-colonial entity. Deductions from the analysis of material

cultural remains sampled from the archaeological site at the churchyard of the Saint Andrew’s

Cathedral (STA) will next be made. Finally, statistically-measured variations in their site

distribution will reflect the nature of the settlement’s spatial organization from which the degree

of social complexity in pre-colonial Singapore can eventually be discerned.

iv

�ABBREVIATIONS

AA

American Antiquity, Journal

AAE

Artibus Asiae, Journal

AP

Asian Perspectives, Journal

BMJ

Brunei Museum Journal

CA

Current Anthropology, Journal

CC

Colombo Court, Archaeological Site

cmbd

centimetres below datum

CODA

The Concise Oxford Dictionary of Archaeology, Publication

EDCC

Economic Development and Cultural Change, Journal

EFEO

École Française d'Extrême-Orient

EMP

Empress Place, Archaeological Site

FTC

Fort Canning Hill, Archaeological Site

IILJ

Institute of International Law and Justice

IPPA

Indo-Pacific Prehistory Association

ISEAS

Institute of Southeast Asian Studies, Singapore

v

�JAA

Journal of Anthropological Archaeology

JAMT

Journal of Archaeological Method and Theory

JASB

Journal of the Asiatic Society of Bengal

JFA

Journal of Field Archaeology

JIAEA

Journal of the Indian Archipelago and Eastern Asia

JMBRAS

Journal of the Malayan Branch of the Royal Asiatic Society; later

renamed as the Journal of the Malaysian Branch of the Royal Asiatic

Society (also JMBRAS) in 1964 1

JSBRAS

Journal of the Straits Branch of the Royal Asiatic Society; later

renamed as the Journal of the Malayan Branch of the Royal Asiatic

Society in 1923 2

JSEAS

Journal of Southeast Asian Studies

LAA

Latin American Antiquity, Journal

MBRAS

The Malaysian Branch of the Royal Asiatic Society

MS

Manuscript

NAG

National Art Gallery, Archaeological Site

NMTN

Nusantao Maritime Trading Network

NUS

National University of Singapore

OPH

Old Parliament House, Archaeological Site

1

“Annual Report of the Malayan Branch Royal Asiatic Society for 1963,” in Journal of the Malayan Branch of the Royal Asiatic

Society (JMBRAS) 37,1 (July 1964), p. 171-2.

2

“Proceedings of the Annual General Meeting,” in Journal of the Straits Branch of the Royal Asiatic Society (JSBRAS) 85 (1922),

p. iv.

vi

�PHC

Parliament House Complex, Archaeological Site

RIMA

Review of Indonesian and Malayan Affairs, Journal

SEAMO

Southeast Asian Ministers of Education Organization

SCC

Singapore Cricket Club, Archaeological Site

SM

Sejarah Melayu, Publication

SO

Suma Oriental, Publication

SOAS

School of Oriental and African Studies, University of London

SPAFA

SEAMO Project in Archaeology and Fine Arts

SMJ

The Sarawak Museum Journal

STA

Saint Andrew’s Cathedral Churchyard, Archaeological Site

TOCS

Transactions of the Oriental Ceramic Society, Journal

TP

T’oung Pao, Journal

VCH

Victoria Concert Hall, Archaeological Site

WA

World Archaeology, Journal

vii

�LIST OF TABLES

I.

Quantitative Distribution of Sample STA Artefacts

…………………………..65

II.

Quantitative Distribution of Earthenware Vessels in Sample STA Artefacts based

on Rim Sherds

……………………………………………………………..66

III.

Quantitative Distribution of Stoneware Vessels in Sample STA Artefacts based on

Rim Sherds

……………………………………………………………………...67

IV.

Quantitative Distribution of Porcelain vessels in Sample STA Artefacts based on

Rim Sherds

……………………………………………………………………...68

V.

Quantitative Distribution of Metals in Sample STA Artefacts ………………….69

VI.

Totals, Percentages, and the Number of Pieces Per Gram of Classified Ceramic

Sherds ……………………………………………………………………………....70

VII.

Totals, Percentages, and the Number of Pieces Per Gram of Classified Ceramic

Sherds by Area

……………………………………………………………..70

VIII.

Totals, Percentages, and the Number of Pieces Per Gram of Classified Ceramic

Rim Sherds by Area ……………………………………………………………..71

IX.

Chi-Squared Test of Significance Between Ceramic Variety and Spatial

Distribution …………………………………………………………………….102

X.

Chi-Squared Value of Calculation

…………………………………………..103

viii

�LIST OF FIGURES

1.

Map indicating existing archaeological sites, landmarks and known boundaries of

pre-colonial Singapore

……………………………………………………...2

2.

Three fragments of the Singapore Stone

3.

Map of reconstructed 14th century settlement in Singapore superimposed on 1836

map of Singapore town drawn by J. B. Tassin

………..............................25

4.

Abstract model for Exchange between a Drainage Basin Centre and an Overseas

Power ………………………………………………………………………………29

5.

The principal [orthogenetic] urban hierarchies in Southeast Asia in the second

half of the 14th century ……………………………………………………………..33

6.

Kerimun Islands to Pedra Branca

7.

STA Site Map (2003-4) indicating the thesis’s division of the site into four

quadrants for comparative analysis ....................................................................57

8.

Coarse-tempered earthenware brick or tile sherd, STA 5

9.

Coarse-tempered earthenware ‘trivet’ or structural ornamentation sherds,

STA ………………………………………………………………………………72

10.

Coarse-tempered ‘Saw-Tooth with Flame’ impressed earthenware pottery body

sherds, STA 13A

……………………………………………………………..73

11.

Medium-tempered earthenware pottery rim sherds, STA 9

12.

Medium-tempered earthenware pottery knobbed lid sherds, STA 50

……………………………………………………………………………………….74

13.

Medium-tempered decorated (paddle-impressed) earthenware pottery body

sherds, STA 9 ...……………………………………………………………………74

14.

Medium-tempered slipped earthenware pottery rim and body sherds, STA 16

……………………………………………………………………………………….75

…………………………………...11

……………………………………………45

ix

…...……………..72

………………….73

�15.

High-fired black-burnished earthenware pottery rim sherds, STA 59

………………..……………………………………………………………………...75

16.

High-fired black-burnished carved earthenware pottery body sherds with ‘Circleand-Ring’ motif, STA 5

……………………………………………76

17.

High-fired mercury-jar type earthenware base sherd, STA 5 ……………….....76

18.

Fine-paste earthenware pottery rim sherds, STA 58 …………………………..77

19.

Fine-paste earthenware pottery rim sherds with ‘apple-green’ glaze, STA 55

……………………………………………………………………………………….77

20.

Fine-paste decorated (Punctated ‘Dot-and-Ring’ motif bordered with double rib

lines) earthenware pottery body sherds, STA 7

…………………………..78

21.

Fine-paste earthenware kendi spout sherds, one with ‘rifled’ interior, STA 58

……………………………………………………………………………………….78

22.

Type A, B and C stoneware pottery inclusion patterns, STA 5………………….79

23.

Buff versus brittle stoneware mercury-jar rim sherds, STA 5 ……………...…..79

24.

Buff versus brittle stoneware mercury-jar base sherds, STA 51

25.

Brittle versus buff stoneware pottery rim sherds with luted lugs, STA 5

.....................................................................................................................................80

26.

Brittle versus buff stoneware pottery body sherds, STA 5

27.

Buff stoneware basin rim sherds, STA 50

28.

Buff stoneware basin rim sherd with folded ‘Pie-Crust’ fringe, STA 6

.....................................................................................................................................82

29.

Brittle stoneware pottery body sherds with glaze, STA 7

30.

Brittle stoneware pottery base sherds, STA 5 …………………………………...83

31.

Buff stoneware pottery base sherds, STA 50 …………………………………...83

32.

Buff purple-ware pottery rim sherd, STA 5

33.

Brittle purple-ware pottery rim sherd with luted lug, STA 7 ………………….84

34.

Assorted green-ware porcelain pottery rim sherds, one with an exterior lotus leaf

relief, STA 5

……………………………...…………..………………….85

35.

Green-ware porcelain bowl sherd with a foliated rim and interior motif, STA 7

……………………………….………………………………………...…………….85

36.

Green-ware porcelain bowl base sherd, STA 51

37.

Assorted green-ware porcelain pottery base sherds, STA 50 ………………….86

x

………....80

.............................81

…...………………………………81

………………….82

………………………………...…84

…………………………..86

�38.

Assorted green-ware porcelain pottery body sherds, one with ‘stylized onion-skin

medallion,’ STA 7

…………………………………………………….87

39.

Green-ware porcelain ‘gacuk’, STA 76

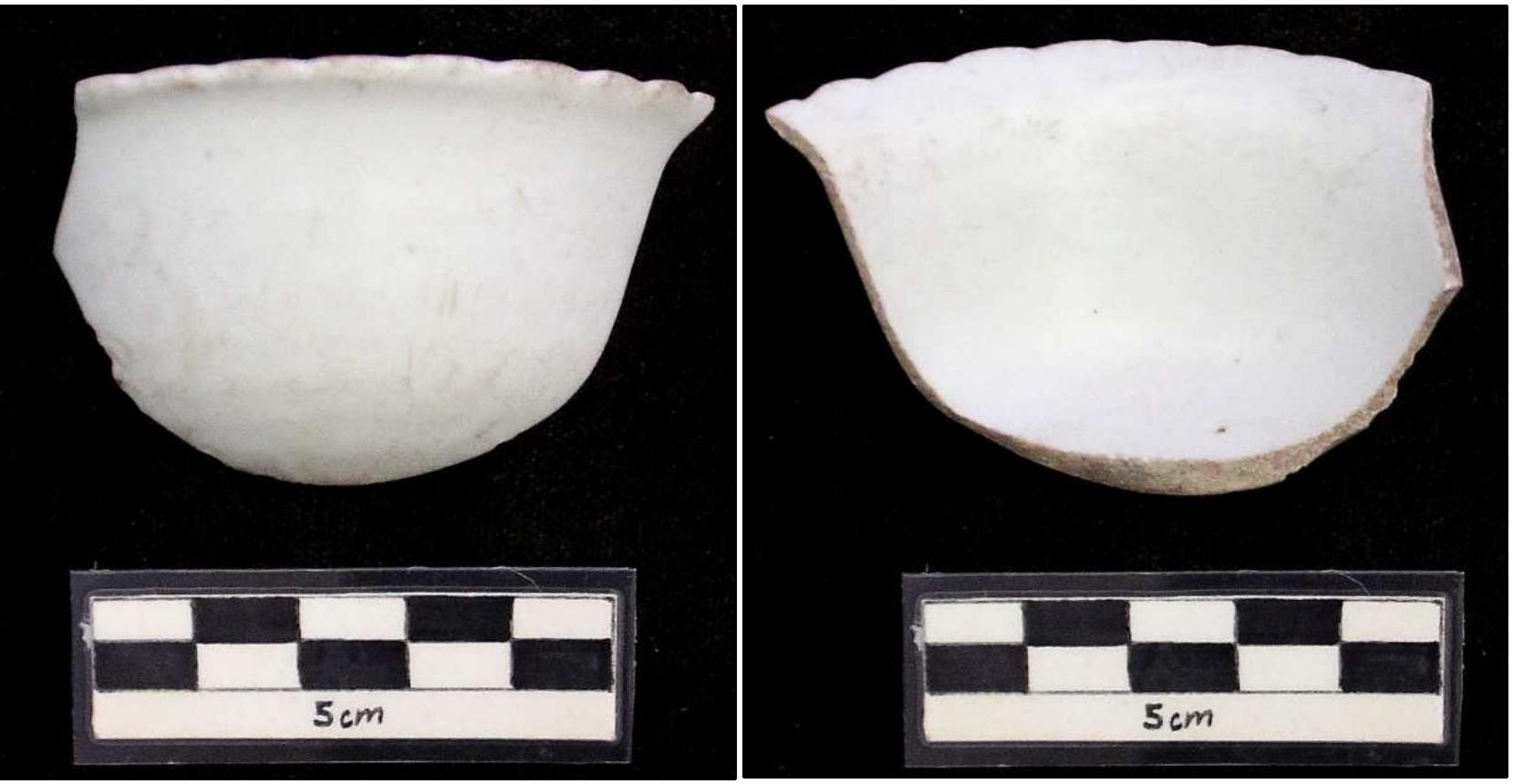

40.

White-ware porcelain cup sherd with foliated rim, STA 5

……………….....88

41.

White-ware porcelain covered box base sherd, STA 26

………………….88

42.

Iron-spotted white-ware porcelain pottery body sherds, STA 9

43.

Blue-and-white porcelain cup rim sherds with exterior chrysanthemum and

foliage motifs and interior classic scrolls and key-fret motifs, STA 50

……………………………………………………………………………………….89

44.

Blue-and-white porcelain bowl rim sherd with an exterior foliage motif and

interior classic scrolls motif, STA 9 ……...…………………………………….90

45.

Blue-and-white porcelain bowl rim sherds with an exterior stylised lotus petals

panelled motif and interior chrysanthemum flower with foliage motif, STA 16.

……………………………………………………………………………………….90

46.

Octagonal blue-and-white vase neck or body sherds with an exterior panelled

classic scrolls motif and luted interior, STA 7 …………………………………...91

47.

Blue-and-white porcelain cup rim and base sherds with an exterior foliated motif,

interior classic scrolls motif and calligraphic illustration of ‘longevity’ on the

interior centre medallion, STA 50

………………………………………........91

48.

Misfired or degraded blue-and-white porcelain pottery body sherds, STA 59

……………………………………………………………………………………….92

49.

Misfired or degraded porcelain pottery base sherd, STA 18A

50.

Metal slag, STA 7 and 26

51.

Metal nails, fishing hooks and other objects, STA 26 …………………………..93

52.

Bronze bangle fragment, STA 18A

53.

‘明道元宝’ (Míng Dào Yuán Băo), Northern Song dynasty coin, 1032-3 CE,

STA 42

……………………………………………………………………...94

54.

Either ‘崇宁通宝’ (Chóng Níng Tōng Băo), ‘崇宁元宝’ (Chóng Níng Yuán

Băo), or ‘崇宁重宝’ (Chóng Níng Zhòng Băo), Northern Song dynasty coin,

1102-1106 CE, STA 50

…………………………………………………….95

55.

Sri Lankan coin, circa 13th-14th centuries CE, STA 16

56.

Crucible-like stone with a rectangular depression on one side, STA 58

……………………………………………………………………………………….96

…………………………………...87

…………89

…………92

…………………………………………………….93

……………………………………………94

xi

………………….95

�57.

Stone structural ornamentation fragments with ornate carved motif on surface,

STA 13A

……………………………………………………………………...96

58.

Sand Grain Sizing Folder

59.

Charts for Estimating Proportions of Mottles and Coarse Fragments…………97

60.

Mohs’ Hardness Scale and Substitutes

61.

Approximate age of STA Site derived from a selection of sampled artefacts

……………………………………………………………………………………….98

…………………………………………………….97

xii

…………………………………...98

�I.

INTRODUCTION

To write a history of the old Singapura would be something like

the task imposed upon the children of Israel by Pharaoh:

for where should one seek the straw to make those bricks with?

Charles Otto Blagden, 1921. 3

Over the last 26 years, large amounts of material cultural remains or ‘artefacts’

approximately dating to the 14th century CE have been recovered from 10 archaeological sites

on Singapore Island. 4 These sites are all located within an area bound by Fort Canning Hill

(FTC) to the north, the Singapore River to the west Stamford Road to the east and the Straits

of Singapore to the south. 5 Coincidentally, Malay oral tradition and written records, most

notably the Malay Annals (Sejarah Melayu (SM) or Sulalat us-Salatin), claim that a polity

known as ‘Singapura’ was established on the island of ‘Temasek’ by a semi-divine prince

around the same region and period. 6 From as early as 1819, these artefacts have been associated

by historians and scholars alike with a hypothetical settlement and polity derived from

inferences drawn from the SM about ‘Temasek-Singapura.’ It is the present consensus that

these artefacts belong to a complex port-city which once existed on Singapore Island in precolonial times. Despite almost two centuries of historical research however, very few of the

political, cultural and socio-economic aspects of this settlement, its relationship with

neighbouring polities and its significance within Southeast Asian pre-colonial history can be

confirmed by verifiable historical evidence. Scholarship on pre-colonial Singapore history has

3

Charles Otto Blagden, “Singapore prior to 1819,” in One Hundred Years of Singapore. Volume 1, ed. Walter Makepeace, Gilbert

E. Brooke & Roland St. John Braddell (Singapore: Oxford University Press, 1991), p. 1.

4

Fort Canning Hill (FTC), Parliament House Complex (PHC), Old Parliament House (OPH), Empress Place (EMP), Colombo

Court (CC), Singapore Cricket Club (SCC), Saint Andrew’s Cathedral (STA), National Art Gallery (NAG), Victoria Concert Hall

(VCH) and the Padang.

5

The settlement was also surrounded by salt marshes to the north-east and north-west beyond FTC and the old wall until 1822; see

John Crawfurd, Journal of an Embassy from the Governor General of India to the Courts of Siam and Cochin China. Volume I

(London: Henry Colburn and Richard Bentley, 1830), p. 68-70.

6

C. C. Brown, Malay Annals (Selangor Darul Ehsan: MBRAS, 2009), p. 30-1.

1

�N

C

C

1

B

7

C

10

8

5

2

3

6

9

4

A

Pre-colonial

Archaeological Sites:

1. Fort Canning Hill

2. Parliament House

Complex

3. Old Parliament

House

4. Empress Place

5. Colombo Court

6. Singapore Cricket

Club

7. Saint Andrew’s

Cathedral

8. National Art

Gallery

9. Victoria Concert

Hall

10. Padang

Pre-colonial

Landmarks:

A. Singapore Stone

B. Old Wall and Moat

C. Terraces and Brick

Foundations

FIGURE 1. Map indicating existing archaeological sites, landmarks and known boundaries

of pre-colonial Singapore.

Source: Google Earth, Imagery Date: 4 June 2011, altitude 7668ft.

2

�only recently started to advance from the results of early- to mid-20th century colonial research,

while archaeology as an academic field in Singapore remains in its infancy despite its

promising inception in the 1980s.

HYPOTHESIS

This thesis aims to fill this lacuna of knowledge by determining the level of social

organization within this pre-colonial settlement through the historical and archaeological

analysis of a sample of pre-colonial artefacts recovered from excavations at the Saint Andrew’s

Cathedral Churchyard (STA) between 2004 and 2005. Specifically, the present hypothesis

assumes that a correlation exists between artefacts and social status in a socially-complex precolonial Singapore polity. The basic assumption on which this hypothesis rests is the general

observation that elite members of societies have the desire and means to purchase and consume

significantly more high-value goods than their non-elite counterparts as a result of ‘unequal

social exchanges.’ 7

Similar research has also demonstrated that greater socio-economic and political

complexity in pre-colonial Southeast Asian societies is typically accompanied by the

development of a ‘political economy’ where certain goods function as a ‘material fund of power’

which is used to ‘reinforce social inequality and political authority, with hereditary ‘elites’

controlling the specialized production and exchange of such goods. 8 Within the context of the

STA archaeological site, this would manifest itself in a distinct and non-random pattern within

the spatial distribution of the artefact sample pool selected for this research. Therefore, certain

areas within the STA site which functioned as the former elite residences should have a higher

proportion of such goods – which are usually of a higher economic cost – than non-elite

residential zones. A random distribution pattern of artefacts within the site will therefore

illustrate the null hypothesis (H0) instead, where there is no correlation between social status

7

Charles Maisels, The Archaeology of Politics and Power. Where, When and Why the First States Formed (Oxford: Oxbrow Books,

2010), p. 343-7.

8

Laura Lee Junker, “The Development of Centralized Craft Production Systems in A.D. 500-1600 Philippine Chiefdoms,” Journal

of Southeast Asian Studies (JSEAS) 25,1 (March 1994), p. 3.

3

�and material culture and hence, suggest that the settlement did not have a complex, stratified

society.

This hypothesis predominantly relies on the abundance of ceramics or pottery sherds

recovered from the STA site, as this class of artefacts accounts for more than 90 percent of the

total amount of artefacts sampled by weight and count. Significantly, not only do ceramics

encode social information concerning important social distinctions within a society, they are

also useful in the illustration of intra- and inter-site social variation. 9 Since the study of social

organization in complex societies is largely the study of social ranking, the disparity between

the rich and poor should be visible in terms of ownership, access to resources, facilities and

status. 10 In the absence of grandiose building and structural remains which usually define this

disparity in other archaeological sites, the study of archaeological ceramics, their distribution

patterns on the site as well as their relationship with social organization and structure rises to

the fore.

PRIMARY SOURCES

Prior to the availability of archaeological sources however, the reconstruction of precolonial Singapore in history was indeed – as Blagden correctly observed – fraught with

difficulty. To quote historical geographer Paul Wheatley, it is ‘doubly unfortunate that there

should be a complete lack of indigenous written sources [on the Malay Peninsula] before the

sixteenth century.’ 11 Hence, if the history of this island before the arrival of the British is the

brick historians seek to mould, there are scarcely any reliable primary textual sources which

scholars can use as straw. No indigenous records are known to have survived until the

compilation of the SM (Raffles Manuscript (MS) No. 18) in the 17th century and its recensions

by various Malay chroniclers over the next few centuries. 12 Significantly, no other source

9

Carla M. Sinopoli, Approaches to Archaeological Ceramics (New York: Plenum Press, 1991), p. 119-42.

Colin Renfrew & Paul Bahn, Archaeology. Theories, Methods and Practice. Fourth Edition (London: Thames & Hudson, 2004),

p. 213.

11

Paul Wheatley, The Golden Khersonese. Studies in the Historical Geography of the Malay Peninsula Before A.D. 1500 (Kuala

Lumpur: University of Malaya Press, 1961), p. v.

12

Richard Olaf Winstedt, “A History of Malay Literature,” JMBRAS 17,3 (January 1940), p. 106-9.

10

4

�besides the SM explains the relationship between the toponyms of ‘Temasek’ and ‘Singapura,’

where it clearly states that the first king of the settlement, ‘Sang Utama’ or ‘Sri Tri Buana,’

‘established a city at Temasek, giving it the name of Singapura’ sometime in 1299. 13

Nonetheless, the SM’s narrative does not reveal much about the polity’s social organization;

as a genealogy of the later Melakan and Johor Sultans, the SM elaborates instead on the

founding myth of Temasek-Singapura, the court intrigue between its five rulers and their

respective courtiers during its supposedly brief 91-year lifespan, and the polity’s demise

under a Majapahit invasion at the end of the 13th century. 14

A number of contemporaneous Chinese accounts are claimed by scholars to have

depicted Temasek-Singapura as well. The first comes in the form of a list of foreign lands

known to the Chinese between 1230 to 1349 entitled Description of the Barbarians of the Isles

(島夷梽畧 Dăo Yí Zhì Lüe), compiled by Wāng Dà Yüan (汪大淵) in the mid-14th century,

under two Chinese toponyms, ‘Lóng Yá Mén’ (龍牙門 or ‘Dragon’s Teeth Gate’) and ‘Bān Zú’

(班卒), as well as the name of their residents, the ‘Dān Mǎ Xī’ (單馬錫) barbarians. 15 Wāng

added under the toponym of ‘Xiān’ ( 暹 or ‘Siam’) that the ‘Siamese’ had launched an

amphibious assault on ‘Dān Mǎ Xī’ in the mid-14th century. The attack grew into a month-long

siege of the city wall and moat (城池 Chéng Chí) which was only dispersed with the sighting

of a passing Javanese envoy. 16 According to the History of the Yuan Dynasty (元史 Yuán Shǐ),

Mongol imperial envoys were even sent to ‘Lóng Yá Mén’ asking for ‘tamed elephants.’ 17

Presumably in response to this request, ‘Lóng Yá Mén’ dispatched a mission to China with a

memorial and tribute. 18 While the accounts provide a detailed insight to the settlements and

13

W. Linehan, “The Kings of 14th Century Singapore,” JMBRAS 20,2 (December 1947), p. 60

Brown, Malay Annals p. 31, 23-52; Linehan, “The Kings of 14th Century Singapore,” p. 60, 117-27.

15

Wheatley, The Golden Khersonese, p. 82-6.

16

苏继倾 (Sū Jì Qīng), 《島夷梽畧校释》 (Dăo Yí Zhì Lüe Jiào Shì or ‘An explanation of the Description of the Barbarians of

the Isles’) (北京: 中华书局, 1981), p. 154-5.

17

Hsü Yün-Ts’iao, “Singapore in the Remote Past,” JMBRAS 45,1 (January 1973), p. 3-4.

18

Oliver William Wolters, The fall of Śrīvijaya in Malay History (London: Lund Humphries Publishers Limited, 1970), p. 78.

14

5

�inhabitants listed under these toponyms, the accuracy of ascribing these toponyms to precolonial Singapore however remains disputed to this day. 19

Various 14th century Southeast Asian texts also appear to have mentioned the polity in

passing. A Javanese chronicle, the Pararaton, lists ‘Tumasik’ as one of the lands proposed to

be conquered by Gajah Mada, the famed Prime Minister of the Majapahit kingdom centred in

east Java; 20 ‘Tumasik’ is next declared in another Javanese text of the same period, the

Deśawarṇana (or Nāgarakṛtāgama), as one of many vassals that ‘seek refuge’ and placed

‘under the protection’ of the Majapahit ruler by 1365. 21 It has also been advanced that the

toponym ‘Sach-ma-tich’ (册馬錫 Sách Mã Tích), found in the Vietnamese Annals of 1330, was

a transliteration of ‘Temasek.’ According to the Annals, a Vietnamese Prince, Tran Nhat Duat,

could have served as an interpreter for the envoys from that land. 22

The earliest European sources on pre-colonial Singapore are Tomé Pires’ Suma

Oriental (SO) which was written between 1512 and 1515, and the writings of Afonso

d’Albuquerque, the Portuguese conqueror of Melaka in 1511, compiled by his son Braz

d’Albuquerque as Commentarios do grande Afonso Dalboquerque in 1557. However, Pires

and the d’Albuquerques gave a different account of ‘simgapura’ from that of the SM. According

to them, the settlement’s last ruler, Parameswara, fled Palembang from the Javanese, murdered

and usurped Singapore Island and its strait from its ruler, only to flee again from the wrath of

both the rulers of Siam and Patani. Pires referred to simgapura primarily as a strait (‘sam agy

simgapura que era Rey daquelle canal’ or Sam Agy Simgapura who was king of that channel)

with islands and towns. This is repeated by the d’Albuquerques, who added that the settlement

19

Lin Wo Ling, Long-ya-men Re-identified (Singapore: 新加坡南洋学会出版, 1999), p. 104-10, 123; Paul Michel Munoz, Early

Kingdoms of the Indonesian Archipelago and the Malay Peninsula (Singapore: Editions Didier Millet, 2006), p. 188.

20

I Gusti Putu Phalgunadi, The Pararaton. A Study of the Southeast Asian Chronicle (New Dehli: Sundeep Prakashan, 1996), p.

125.

21

Stuart Robson, Deśawarṇana (Nāgarakṛtāgama) by Mpu Prapañca (Leiden: KITLV Press, 1995), p. 33-4; the present thesis

follows Robson’s orthography of this old Javanese poem.

22

Wolters, History, Culture and Region in Southeast Asian Perspectives (Singapore: Institute of Southeast Asian Studies (ISEAS),

1982), p. 48, cited in John Norman Miksic, Archaeological Research on the “Forbidden Hill” of Singapore: Excavations at Fort

Canning, 1984 (Singapore: National Museum Singapore, 1985), p. 17.

6

�‘was a very large and very populous city – as is witnessed by its great ruins which still appear

to this very day [in the early 16th century].’ 23

Mention of Temasek-Singapura’s existence, decline and fall were found in subsequent

Arabic, Chinese and European maps, texts and other maritime records of the Melakan Strait in

the later centuries, but they were either repeating the narratives found in the SM, Description,

SO and Comentarios, or extremely scant in detail. Not surprisingly, very little is known about

the pre-colonial settlement itself. This paucity of detailed and verifiable information, however,

did not diminish efforts to reconstruct the island’s pre-colonial past of which three

historiographical phases can be distinguished.

LITERATURE REVIEW

The first historiographical phase is characterised by the discovery and historicising of

Temasek-Singapura by early colonial scholarship between the 18th and early-20th centuries.

Knowledge of the SM, as well as another Malay text, the Taju assalatin or Makuta segala rajaraja (‘The Descent of all [Malayan] Kings’), were already communicated to the West by

Dutchmen Petrus van der Worm, François Valentijn, George Hendrik Werndly, as well as

Englishman John Leyden between the late-17th to early-18th centuries. 24 But it was not till the

late-18th century that the SM’s narrative of Temasek-Singapura was first historicized by

William Marsden within three editions of his book, The History of Sumatra, published between

1774 and 1811. Marsden was regarded by early colonial scholars to be ‘the first literary and

scientific Englishman, with the advantage of local knowledge, who wrote about the Malay

countries, with laborious care and scrupulous fidelity.’ 25 This is reflected most in his

condensation of the first six chapters of the SM, covering the descent of the Malays from Raja

23

Armando Cortesão, The Suma Oriental of Tomé Pires. An Account of the East, From the Red Sea to Japan, written in Malacca

and India in 1512-1515 and The Book of Francisco Rodrigues. Rutter of a Voyage in the Red Sea, Nautical Rules, Almanack and

Maps, written and Drawn in the East before 1515. Volume II (London: Hakluyt Society, 1944), p. 229-33; Walter De Gray Birch,

The Commentaries of the Great Afonso Dalboquerque. Second Viceroy of India. Volume III (New York: Burt Franklin, 1970), p.

71-4.

24

William Marsden, The History of Sumatra (Singapore: Oxford University Press, 1986), p. 326; Winstedt “Malay Works known

by Werndly in 1736 A.D.,” JSBRAS 82 (September 1920), p. 163-5.

25

Charles Burton Buckley, An Anecdotal History of Old Times In Singapore (Singapore: Oxford University Press, 1984), p. 2.

7

�Iskandar the ‘Two-Horned’ (Alexander the Great) to the fall of Temasek-Singapura, into two

brief paragraphs so as to omit ‘mythological fable’ in order to retrieve ‘historical fact.’ 26 The

same was done in Thomas Stamford Raffles’ The History of Java in 1816, where he outlined

within a lengthy footnote the genealogical descent of the ‘Malayus’ from Alexander to the

founding of the ‘city of Singa pura’ sometime in 1160. 27 John Crawfurd took the study of

Temasek-Singapura a step further when his book, History of the Indian Archipelago, was

published in 1820. Like Marsden before him, Crawfurd believed that the ‘parent country’ of

the Malays lay in ‘the country of Menangkabao in Sumatra.’ He suggested that the

establishment of ‘Singahpura’ on the Malay Peninsula was a result of a wave of migration of

the ‘Malayu tribe,’ a sub-division of the people of Menangkabao, in a time when ‘a rapid and

unusual start in civilization and population’ lead to a scarcity of land on the ‘great and fertile

plain’ in Sumatra. Crawfurd however was unwilling ‘to attempt any narrative of their affairs’

due to the absence of a ‘full and connecting narrative of the history of any of the Malay states,’

as well as some ‘suspicious circumstances in the detail of events.’ Nonetheless, he considered

Temasek-Singapura as a historical primary colony from which the Malays later dispersed to

colonize the rest of the Malay Peninsula, the Riau-Lingga Islands, Borneo and eventually

returning to Sumatra and established Kampar and Aru. 28

While Marsden, Raffles and Crawfurd generally agreed that Temasek-Singapura was

located somewhere in the southern extremity of the Malay Peninsula, it was Raffles who

advocated Singapore Island as its precise site. On 12 December 1818, Raffles wrote to Marsden

revealing his intent to appropriate for the East India Company the ‘site of the ancient city of

Singapura.’ 29 In a letter addressed to Colonel Addenbrooke on 10 June 1819, Raffles wrote that

he would not have known about the existence of Singapore if not for his ‘Malay Studies.’30

Some scholars have dismissed this claim as ludicrous since the island’s toponym was found in

26

Marsden, The History of Sumatra, p. 327.

Thomas Stamford Raffles, The History of Java (Singapore: Oxford University Press, 1988), p. 108-10.

28

Crawfurd, History of the Indian Archipelago. Volume II. (Edinburgh: Archibald Constable and Co., 1820), p. 371-8.

29

Blagden, “The Foundation of the Settlement,” in One Hundred Years of Singapore. Volume 1, p. 7.

30

Raffles, “The Founding of Singapore,” JSBRAS 2 (December 1878), p. 175, 178.

27

8

�almost every contemporary map of the region in Raffles’ time. 31 They have in fact

misunderstood Raffles, as he referred not just to the existence of the island in the 19th century,

but also to its association with the narrative according to the centuries-old Malay oral and

written tradition canonised in the SM. In his instructions to William Farquhar who was

appointed as the first Resident of Singapore on 6 February 1819, Raffles reiterated that ‘the

latter [Malay rulers] will hail with satisfaction the foundation and the site of a British

establishment, in the centrical and commanding situation once occupied by the capital of the

most powerful Malayan empire then existing in the East.’ 32 Just one week after acquiring a

lease on the south coast of the island for the British East India Company, Raffles wrote another

letter dated 13 February 1819 to the Supreme Government in Calcutta that, ‘a British Station,

commanding the Southern entrance of the Straits of Melaka, and combining extraordinary local

advantages with a peculiarly admirable Geographical position, has been established at

Singapore the ancient Capital of the Kings of Johor.’ 33 Four months later, Raffles wrote in the

letter to Addenbrooke that he had ‘planted the British Flag’ on the ruins of the ancient Capital

of ‘Singapura,’ or ‘City of the Lion’ at the ‘Naval of the Malay countries.’ 34 In another letter to

Marsden dated 21 January 1823, Raffles announced the construction of a bungalow on FTC

where ‘the tombs of the Malay Kings are, however, close at hand.’ 35 Through these letters

written in both official and private capacities, Raffles had implanted the idea of TemasekSingapura as a lost Malay capital and kingdom on Singapore Island firmly in colonial

scholarship.

The credibility of Raffles’ claim was bolstered by other accounts of physical and

material cultural remains of a pre-colonial settlement in the early years of the British settlement

on Singapore Island. According to the Hikayat Abdullah, the autobiography of Raffles’

31

Eunice Thio, “Introduction,” in Singapore. 150 years, ed. Tan Sri Dato’ Mubin Sheppard (Singapore: Times Books International),

p. iii.

32

Thomas Braddell, “Notices of Singapore,” Journal of the Indian Archipelago and Eastern Asia (JIAEA) 7 (1853), p. 326.

33

John Bastin, Letters and Books of Sir Stamford Raffles and Lady Raffles (Singapore: Editions Didier Millet Pte Ltd, 2009), p.

258.

34

Raffles, “The Founding of Singapore,” p. 178.

35

Sophia Raffles, Memoir of the Life and Public Services of Sir Thomas Stamford Raffles (Singapore: Oxford University Press,

1991), p. 535.

9

�associate Abdullah bin Abdul Kadir, the Temenggong once told Farquhar that FTC was known

as Bukit Larangan or ‘Forbidden Hill,’ the site of ‘palaces’ and a royal bath (Pancur Larangan

or Forbidden Spring) belonging to the ‘kings of ancient times.’ Abdullah also noted that fruit

trees of ‘great age’ were found when the land around the hill was cleared. 36 Crawfurd, who

visited the island in 1822, also saw the fruit trees mentioned by Abdullah, suggesting that they

were ‘cultivated by the ancient inhabitants of Singapore’ and found it remarkable that they still

existed ‘after a supposed lapse of near six hundred years.’ Crawfurd also observed that the

northern and western sides of FTC were ‘covered with the remains of the foundations of

buildings, some composed of baked bricks of good quality.’ Near the summit of the hill was a

square terrace of approximately 40 feet to a side which held ‘fourteen large blocks of

sandstone… with a hole in each,’ thought by Crawfurd to be pedestals of wooden posts that

supported a structure, as well as a ‘circular inclosure, formed of rough sandstone’ which he

speculated once contained a Buddhist image and thus, conjectured that the hill was a site of

ancient Buddhist monasteries. Crawfurd also encountered pottery shards found ‘in great

abundance’ as well as Chinese brass coins minted between the ‘tenth and eleventh centuries’

among the ruins. Another terrace was communicated to Crawfurd as the ‘burying-place (or

Keramat) of Iskandar Shah, King of Singapore.’ 37 Besides the ruins on the hill, Raffles was

able to trace in 1819 the remains of the ‘lines of the old city, and of its defences’ within which

the new British station was to be founded; 38 the old rampart was mapped and published as the

‘Old Walls of the City’ by Captain Daniel Ross in the same year. 39 Crawfurd added that it was

a wall approximately ‘sixteen feet’ wide and ‘eight or nine feet’ high which ‘runs very near a

mile from the sea-coast to the base of the hill, until it meets a salt marsh.’ A little rivulet also

ran along the northern face of the wall which formed ‘a kind of moat’ up to the elevated side of

36

A. H. Hill, Hikayat Abdullah (Kuala Lumpur: MBRAS, 2009), p. 142, 168.

Crawfurd, Journal of an Embassy, p. 68-73.

Raffles, Memoir, p. 376.

39

Daniel Ross, “Plan of Singapore Harbour February 1819,” illustrated in Bastin, Letters and Books, p. 254.

37

38

10

�FIGURE 2. Three fragments of the Singapore Stone.

Source: J. W. Laidlay, Journal of the Asiatic Society of Bengal (JASB) 17,2 (1848), pl. 3, opp. p. 68, illustrated

in Miksic, Archaeological Research, p. 41.

11

�the hill where it became a dry ditch. 40 These observations led Crawfurd to conclude that the

settlement was located at the foot of FTC and ‘bounded to the east by the sea, to the north by a

wall, and to the west by a salt creek or inlet of the sea’ which he noted to be like ‘a kind of

triangle.’ 41

The moat, wall and ruins on the hill were not the only pre-colonial remains which

supported the historicity of pre-colonial Singapore as Temasek-Singapura. As the jungles were

cleared and knolls levelled to fill the swamps for the development of the new British factory,

Abdullah recorded that a large, inscribed rock was found at the mouth of the

Singapore River. 42 Presently known as the ‘Singapore Stone,’ Crawfurd described it as ‘a rude

mass’ of stone which was split into ‘two nearly equal parts by artificial means.’

Crawfurd observed also that the inscriptions had characters similar to ‘Pali, or religious

character used by the followers of Buddha,’ which he noted to be found abundantly in Java and

Sumatra. 43 Originally a sandstone boulder approximately three metres tall and three metres

wide, the inscription had covered the inner surface of one-half of the boulder. 50 or 52 lines of

script were inscribed on an area 2.1 metres wide and 1.5 metres high, with approximately 40

lines that were discernible while the first 12 lines at the beginning had been effaced. 44 The

inscription was however badly weathered either by the rain or the action of the tides which

made it difficult to read and hence hard to decipher. In an unfortunate series of events, the stone

was blown up and chiselled away by colonial engineers and labourers in 1843. Drawings of

three inscription fragments were made before they were sent to Calcutta for analysis, but only

one found its way back to the National Museum in Singapore while the other two have yet to

be found. 45 Scholars J. W. Laidlay and Hans Kern later identified the characters to be Kawi, a

mainstream script used in East Java by the 13th century. 46 On this basis, four disparate Sanskrit

40

Crawfurd, Journal of an Embassy. Volume I, p. 68-73.

Ibid., p. 68-70.

42

Hill, Hikayat Abdullah, p. 167.

43

Crawfurd, Journal of an Embassy. Volume I, p. 70

44

Miksic, Archaeological Research, p. 40.

45

Carl Alexander Gibson-Hill, “Singapore Old Strait & New Harbour (1300-1870),” in Memoirs of the Raffles Museum. No. 3, ed.

Carl Alexander Gibson-Hill (Singapore: Government Printing Office, 1956), p. 24.

46

Johannes Gijsbertus de Casparis, Indonesian Paleography: A history of writing in Indonesia from the beginnings to c. A.D. 1500

(Leiden: E. J. Brill, 1975), p. 5.

41

12

�words of ‘salâgalalasayanara,’ ‘ya-âmânavana,’ ‘kesarabharala’ and ‘yadalama’ were

deciphered by Kern, but their meanings remain unknown. 47

Supported predominantly by the SM and pre-colonial material cultural remains, early

colonial scholarship created the historical polity of Temasek-Singapura and established it on

Singapore Island. To quote John Turnbull Thomson in 1849, ‘the site of the present town of

Singapore… on the same spot we were led to believe from the perusal of Malayan history, was

occupied by the ancient one…’ 48 Between 1847 and 1859, members of the British colonial

service and public in Singapore such as Thomson, Edmund Augustus Blundell and Thomas

Braddell published articles in the Journal of the Indian Archipelago and Eastern Asia (JIAEA,

popularly known as ‘Logan’s Journal’) which continued to associate the island with TemasekSingapura. 49 Much of this work was later compiled within what was to be the first unofficial

history of the British colony, Charles Burton Buckley’s An Anecdotal History of Old Times in

Singapore in 1902, where the familiar narrative of Temasek as ‘ancient Singapore’ was

faithfully repeated. 50 This trend of scholarship was continued in the Journal of the Straits

Branch of the Royal Asiatic Society (JSBRAS), later renamed the Journal of the Malayan

Branch of the Royal Asiatic Society (JMBRAS) and after Malaysia’s independence, the Journal

of the Malaysian Branch of the Royal Asiatic Society (also JMBRAS).

As the journals’ chief aim was to ‘investigate subjects connected with the Straits of

Melaka and its neighbouring countries,’ various Chinese, European and Southeast Asian

sources were increasingly cited in historical articles which affirmed the antiquity of the

region. 51 This indirectly substantiated the historicity of the SM and consequently, TemasekSingapura, which were frequently cited in these articles; Blagden was able to declare that

Temasek ‘is certainly Singapore;’ Richard James Wilkinson called Singapore ‘Palembang’s

47

Hans Kern, “Concerning some old Sanskrit Inscriptions in the Malay Peninsula,” JSBRAS 49 (December 1907), p. 100-1.

John Turnbull Thomson, “General report on the Residency of Singapore, drawn up principally with a view of illustrating its

Agricultural Statistics,” JIAEA 3 (1849), p. 618.

49

Edmund Augustus Blundell, “Notices of the History and Present Condition of Malacca,” JIAEA 2 (1848), p. 727; Thomas

Braddell, “Abstract of the Sijarah Malayu or Malay Annals, with Notes,” JIAEA 5 (1851), p. 244.

50

Buckley, An Anecdotal History, p. ix, 18-25.

51

George Frederick Hose, M. A., “Inaugural Address by the President,” JSBRAS 1 (July 1878), p. 1.

48

13

�daughter;’ Richard Olaf Winstedt even accused Dutchman van der Tuuk to have ‘robbed

Singapore of its legendary founder’ by identifying Nila Utama (Sri Tri Buana) with Tillottama,

a nymph of Indra’s heaven. 52 Blagden later enshrined the Temasek-Singapura narrative in the

first chapter of One Hundred Years of Singapore, a historical volume celebrating the centenary

of the island in 1921. 53 The discovery of the cache of pre-colonial gold ornaments at FTC in

1926 further reinforced Winstedt’s belief in the Javanese conquest of Temasek-Singapura in

1360, as armlets bearing decorations in the form of kala heads as well as a ring with a goose

design suggested a Hindu-Javanese provenance from the Majapahit period sometime in the 14th

century. 54 Wilkinson, Winstedt, Anker Rentse, W. Linehan and Mervyn Cecil Franck Sheppard

subsequently grafted the narrative of Temasek-Singapura as well as other references found in

the SM as the prologue to the history of almost every Malay state in British Malaya. 55

Notable Southeast Asian scholars of that generation such as Daniel George Edward

Hall and George Coedès also unquestioningly accepted the assumption that Tumasik (in the

Deśawarṇana) and Temasek (in the SM) was located on Singapore Island, whereas Paul Pelliot

called Singapore (Tumasik or Tĕmasik) ‘Palembang’s colony.’ 56 Despite his contentions on the

historicity of the SM, Oliver William Wolters nevertheless alluded that Temasek-Singapura was

an actual polity, albeit as a less significant ‘trading and piratical kingdom’ than a prosperous

cosmopolitan port of trade. 57 In keeping with this scholarly tradition, Constance Mary

52

D. F. A. Hervey, “Valentyn’s Description of Malacca,” JSBRAS 13 (June 1884), p. 62-6; E. Koek, “Portuguese History of

Malacca,” JSBRAS 17 (June 1886), p. 117-8; Blagden, “Notes on Malay History,” JSBRAS 53 (September 1909), p. 143-62;

William George Maxwell, “Barretto de Resende’s Account of Malacca,” JSBRAS 60 (December 1911), p. 18-9; Richard James

Wilkinson, “The Malaccan Sultanate,” JSBRAS 61 (June 1912), p. 67; Winstedt, “The Founder of Old Singapore,” JSBRAS 82

(September 1920), p. 127; A. Caldecott, “The Malay Peninsula in the XVIIth & XVIIIth Centuries,” JSBRAS 82 (September 1920),

p. 129-32; Winstedt, “The Early History of Singapore, Johore & Malacca; an outline of a paper by Gerrit Pieter Rouffaer,” JSBRAS

86 (November 1922), p. 258-60; Wilkinson, “ Early Indian Influence in Malaysia,” JMBRAS 13,2 (October 1935), p. 8-9, 15;

Wilkinson, “Old Singapore,” JMBRAS 13,2 (October 1935), p. 17-21; Linehan, “The Kings of 14th Century Singapore,” p. 117-27.

53

Blagden, “Singapore prior to 1819,” p. 1-5.

54

Winstedt, “Gold Ornaments dug up at Fort Canning, Singapore,” JMBRAS 6,4 (November 1928), p. 1-4; Miksic, Archaeological

Research, p. 42-3.

55

Wilkinson, A History of the Peninsular Malays with Chapters of Perak and Selangor (Singapore: Kelly & Walsh, Limited, 1920),

p. 18-31; Winstedt, “A History of Johore (1365-1895),” JMBRAS 10,3 (December 1932), p. 6; Winstedt & Wilkinson, “A History

of Perak,” JMBRAS 12,1 (December 1932), p. 6; Anker Rentse, “History of Kelantan. I.,” JMBRAS 12, 2 (August 1934), p. 44-8;

Winstedt, “A History of Selangor,” JMBRAS 12,3 (October 1934), p. 1-2; Winstedt, “Negri Sembilan. The History, Polity and

Beliefs of the Nine States,” JMBRAS 12,3 (October 1934), p. 42; Winstedt, “A History of Malaya,” JMBRAS 13,1 (March 1935),

p. 31-44; Linehan, “History of Pahang,” JMBRAS 14,2 (May 1936), p. 5-11; Mervyn Cecil Franck Sheppard, “A Short History of

Trengganu,” JMBRAS 22,3 (June 1949), p. 3-6.

56

Daniel George Edward Hall, A History of South-East Asia. Fourth Edition (Hampshire: Palgrave Macmillan, 1995), p. 224; Paul

Pelliot, Notes on Marco Polo. Volume II (Paris: Imprimerie Nationale, 1963), p. 772, 839; George Coedès, The Indianized States

of Southeast Asia (Kuala Lumpur: University of Malaya Press, 1968), p. 241.

57

Wolters, The fall of Śrīvijaya in Malay History, p. 11, 78-80.

14

�Turnbull’s A History of Modern Singapore begins with the citation of various references to precolonial Singapore as well as the SM’s account of Temasek-Singapura. 58

Having supposedly established the historicity of Temasek-Singapura, the second

historiographical phase in turn saw the elaboration of Temasek-Singapura as a port-polity

within a wider context of maritime history in the longue durée. Scholars began to corroborate

European and Southeast Asian texts – well studied by this time – with ancient Chinese and

Arabic records in their study of pre-colonial Southeast Asia. A general method for ‘the reconstruction of the ancient pictures of Malaya’ was hence inaugurated by the identification of

‘a number of ancient toponyms, Greek, Indian, Chinese, Arabic and so forth,’ through a

coinciding of ‘the geographical, historical, and etymological data.’ 59 Regardless, the SM’s

narrative of Temasek-Singapura remained the dominant narrative in the study of Singapore’s

pre-colonial history.

Consequently, research shifted to the search for ‘Temasek-Singapura’ within historical

references to the Malayan Peninsula as well as the Melakan and Singapore Straits. In his study

of Ptolemy’s trans-Gangetic geography, Gerolamo Emilio Gerini cites the SM as evidence for

locating ‘Tamasak, or Ujong Tanah of the Malays’ on Singapore Island, as well as phonetically

associating it with the toponyms of ‘Bêtumah’ in Arabic, Dān Mă Xī (淡馬錫) in Chinese,

‘Tamus’ or ‘Tamarus’ in French, and Tumasik in the Deśawarṇana. 60 At the same time, Warren

D. Barnes directed attention to the maritime use of the Singapore Strait(s) in pre-colonial times.

Citing Chinese and European sources from 1436, Barnes argued that the ‘old Straits of

Singapore are none other than the present Keppel Harbour,’ a waterway that passes between the

south-western coast of Singapore and its islands Pulau Brani and Pulau Blakang Mati (also

known as Sentosa Island). 61 Having translated and studied Chinese maritime records, William

58

Constance Mary Turnbull, A History of Modern Singapore. 1819-2005 (Singapore: NUS Press, 2009), p. 19-23.

Roland Braddell, “Notes on Ancient Times in Malaya,” JMBRAS 20,1 (June 1947), p. 162; see also Wolters, Early Indonesian

Commerce. A study of the origins of Śrīvijaya (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1967), p. 170-1.

60

Gerolamo Emilio Gerini, Researches on Ptolemy’s Geography of Eastern Asia (London: Royal Asiatic Society & Royal

Geographical Society, 1909), p. 199-200, 533, 775, 821.

61

Warren D. Barnes, “Singapore old Straits and New Harbour,” JSBRAS 60 (December 1911), p. 25-31.

59

15

�Woodville Rockhill believed that the Chinese toponym of ‘Dān Mă Xī’ referred to Temasek

and therefore, its adjacent waterway – Lóng Yá Mén – must refer to the Singapore Strait. 62 In

his study of studied various Chinese sailing directions across the centuries, John Vivian Gottlieb

Mills concurred in the identification of Singapore Island and its strait with the toponyms of Dān

Mă Xī and Dragon’s Teeth Gate respectively, but argued instead that the ‘old strait’ lay along

the present Strait of Singapore, delineated by its southern shores and the northern coasts of

Batam and Bintan Islands in Indonesia. 63 Like his father Thomas Braddell, Roland St. John

Braddell advocated that ‘Tan-ma-hsi is a transliteration of Temasek and, beyond doubt, is

Singapore.’ Braddell supported Barnes’ idea that the old Strait was along Keppel Harbour and

identified by the toponym of Dragon’s Teeth Gate. 64 Reiterating the views of Barnes and

Braddell, both Carl Alexander Gibson-Hill and Hsü Yün-Ts’iao staunchly supported the

location of Temasek Singapore and the Dragon’s Teeth Gate at Singapore and Keppel Harbour

respectively. 65 Citing the work of Barnes and Gibson-Hill, Wheatley supports the association

of Chinese toponyms Dān Mă Xī and the Dragon’s Teeth Gate with Singapore and Keppel

Harbour as well. In addition, Wheatley brought ‘Bān Zú,’ a locality was mentioned by Wāng

to be situated behind the Dragon’s Teeth Gate, to the discussion, arguing that it ‘can only be

the eminence which dominates Singapore City, namely Fort Canning Hill.’ 66

Significantly, Coedès’ ‘rediscovery’ of Srivijaya in 1918, believed at that time to be a

great pre-colonial Southeast Asian maritime thalassocracy, provided a firm historical context

for the interpretation of Temasek-Singapura as a polity built upon the foundation of maritime

trade. 67 This led Blagden, who had worked with Coedès on the transliteration of Malay

inscriptions of Srivijaya, to suggest that Temasek-Singapura and ‘a number of “Straits

Settlements” ’ on the Malay Peninsula came under the influence of Srivijaya for several

62

William Woodville Rockhill, “Notes on the Relations and Trade of China with the Eastern Archipelago and the Coasts of the

Indian Ocean during the Fourteenth Century. Part II,” T’oung Pao (TP), Second Series 16,1 (March 1915), p. 61, 129-32.

63

John Vivian Gottlieb Mills, “Malaya in the Wu-Pei-Chih Charts,” JMBRAS 15,3 (December 1937), p. 21-8; Mills, “Arab and

Chinese Navigators in Malaysian Waters in about A.D. 1500,” JMBRAS 47,2 (December 1974), p. 25-32.

64

Roland Braddell, “Lung-Ya-Men and Tan-Ma-Hsi,” JMBRAS 23,1 (February 1950), p. 37-51.

65

Gibson-Hill, “Singapore: Notes on the History of the Old Strait, 1580-1850,” JMBRAS 27,1 (May 1954), p. 163-214; GibsonHill, “Singapore Old Strait & New Harbour (1300-1870),” p. 11-115; Hsü, “Singapore in the Remote Past,” p. 1-9.

66

Wheatley, The Golden Khersonese, p. 82-6.

67

George Coedès, “The Kingdom of Sriwijaya,” in Sriwijaya. History, Religion & Language of an Early Malay Polity, ed. PierreYves Manguin (Kuala Lumpur: MBRAS, 1992), p. 1-40.

16

�centuries. 68 With the decline of Srivijaya by the end of the 13th century, Blagden argued that

Singapore, with kings ‘descended from the royal family of Palembang,’ became independent

and capitalized on its ‘unique position’ as a ‘short cut’ for trade between the East and West. 69

Wheatley proceeded to label the period between the 13th to 14th centuries on the Malay

Peninsula as the ‘Century of Singhapura,’ which was preceded by the decline of Srivijaya and

succeeded by the next ‘Century of Mĕlaka.’ 70 In recent years, Michel Jacq-Hergoualc’h argued

that Temasek-Singapore was ‘favoured by the irreversible weakening of the political entity that

was Śrīvijaya-Palembang-Jambi’ effected by Javanese incursions, and stated that the ‘rapid

development of Temasek-Singapore is undeniable’ in the 14th century. 71 Paul Michel Munoz

also lists Temasek-Singapura as a ‘post-Srivijayan emporium’ in the Malay Archipelago during

the ‘late Classical period.’ 72 In his seminal study of the Malays, Anthony Crothers Milner

assumed ‘Tumasek’ to be Singapore and the Siamese and Javanese attacks on it in the 14th

century as historical facts. 73

While the archaeological record had clearly been the motivation behind much research

on pre-colonial Singapore in the last two historiographical phases, it was merely considered as

a physical indicator of the island’s antiquity which supported existence of Temasek-Singapura

as a historical polity; the artefacts themselves were never analysed to elicit information about

the settlement itself. In the words of Wong Lin Ken, the antiquity of Singapore ‘does not bear

serious investigation.’ Nonetheless, he believed that the trade which came to Singapore in the

19th century ‘was not merely the result of the transfer of an existing trade into new channels,’

but that of Raffles putting into operation ‘the principal of the ancient Emporia,’ which he

thought was the ‘basis of commerce in the Malay Archipelago.’ 74 As the old wall and ruins on

FTC, the Singapore Stone and other traces of material cultural remains still visible in

68

Coedès, “The Malay Inscriptions of Sriwijaya,” in Sriwijaya, p. 43-5.

Blagden, “The Empire of the Maharaja, King of the Mountains and Lord of the Isles,” JSBRAS 81 (March 1920), p. 25-8.

70

Wheatley, Impressions of the Malay Peninsula in Ancient Times (Singapore: Eastern Universities Press LTD, 1964), p. 101-118.

71

Michel Jacq-Hergoualc’h, The Malay Peninsula. Crossroads of the Maritime Silk Road (100 BC – 1300 AD) (Leiden: Brill,

2002), p. 491.

72

Munoz, Early Kingdoms, p. 185.

73

Anthony Crothers Milner, The Malays (Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell, 2008), p. 36.

74

Wong Lin Ken, The Trade of Singapore (Bandar Puchong Jaya: MBRAS, 2003), p. 159, 194-204.

69

17

�Crawfurd’s days fell to urban redevelopment, textual sources came to supplant the

archaeological record in the research on pre-colonial Singapore for most of the 20th century.

The reconstruction of Temasek-Singapura from archaeological and historical sources

hence constitutes the third and present historiographical phase of Singapore’s pre-colonial

history. Through the use of artefacts and archaeological approaches in historical research, a

semblance of the pre-colonial settlement was finally developed and supported by concrete

evidence. This was initiated with the advent of archaeological excavation and research in

Singapore by John Norman Miksic in 1984. Despite the loss of pre-colonial structural and

building foundation remains, Miksic managed to identify specialized activities that were

conducted within two separate localities – FTC and Parliament House Complex (PHC) –

through the meticulous and tedious study of thousands of artefacts recovered from these sites.

In line with Crawfurd’s suggestion that FTC was a site of Buddhist worship and monasteries,

Miksic inferred from the results of his excavations that ‘a centre of ceremonial activity… or

perhaps a monastery’ was located in the vicinity of FTC. 75 The recovery of misshapen glass

globules, shards and beads on FTC in 1988 led Miksic to suggest also the presence of an

artisan’s glass-recycling workshop as well. 76 In consideration of Crawfurd’s observations as

well as the Malay tradition of the hill as the site of ancient kings as recounted by the

Temenggong and canonized in the SM, Miksic concluded that ‘FTC can be interpreted as a

craftsmen’s quarter within a palace and temple precinct.’ 77

Miksic’s work inspired further archaeological research on artefacts recovered from

other pre-colonial archaeological sites in Singapore. Having studied the collection of bronze,

iron and gold artefacts, coins as well as huge quantities of metal slag recovered from

excavations at PHC, Shah Alam Mohd. Zaini argued in his M.A. thesis that the PHC was a site

75

Miksic, Archaeological Research, p. 90.

Miksic, “Beyond the Grave: Excavations North of the Keramat Iskandar Shah, 1988,” in Heritage, ed. Lee Chor Lin (Singapore:

National Museum, Singapore, 1989), p. 55-6.

77

Miksic, “14th-Century Singapore. A Port of Trade,” in Early Singapore. 1300s-1819. Evidence in Maps, Texts and Artefacts, ed.

Miksic & Cheryl-Ann Low Mei Gek (Singapore: Singapore History Museum, 2004), p. 52.

76

18

�of a metal-working sector in pre-colonial Singapore. 78 The presence of numerous coins also

spurred Miksic to infer that commercial activities were conducted in the vicinity of PHC as

well. 79 Following Miksic’s suggestion that earthenware excavated in Singapore were ‘made by

local inhabitants,’ earthenware ceramics from the PHC site formed the subject of another M.A.

thesis by Omar Chen Hong Liang. 80 Similarities in appearance and manufacture with

earthenware shards from other regional archaeological sites such as Johor Lama in Malaysia,

Tanjong Kupang in Brunei and Kota Cina in Sumatra had suggested to Chen the possibility of

a pre-colonial ‘Malay’ pottery tradition and to study these artefacts within this context.

Compositional and morphological analysis of earthenware shards allowed him to identify the

various types and functions of earthenware pottery, as well as reconstruct their approximate

production processes. Chen concluded that PHC earthenware, specifically ‘paddle-stamped’

pottery, was manufactured in around the 12th century and suggested that pottery manufacture

ceased with the demise of the settlement sometime around the 15th century. 81

A third M.A. thesis by Derek Heng Thiam Soon presents a hypothetical model of the

pre-colonial settlement on Singapore Island to which he, taking the lead from Wheatley,

ascribed the toponyms of both Bān Zú and Temasek. Drawing heavily from Miksic’s research,

Heng utilized ‘historical sources, colonial accounts and results derived from the data of the

archaeological excavations and surveys’ to ‘establish a plausible working model against which

further studies may be carried out.’ Heng argued that the settlement was a ‘classical period

Malay trading port polity’ with an economic hinterland at the Riau Archipelago. This was in

turn derived from Miksic’s suggestion of close economic ties between Singapore and Riau on

the basis of a similar distribution of Chinese green-ware ceramics in the two areas. 82 An

international player exporting a wide range of commodities such as hornbill casques and

78

Shah Alam Mohd. Zaini. Metal Finds and Metal-working at the Parliament House Complex, Singapore. M.A. Thesis. University

of Michigan. 1997.

79

Miksic, “14th-Century Singapore,” p. 52.

80

Miksic, Archaeological Research, p. 55-88.

81

Omar Chen Hong Liang. Earth to Earth: An Investigation into the Occurrence of Earthenware Artefacts at the Parliament House

Complex Site. M. A. Thesis. National University of Singapore (NUS), 2001.

82

Miksic, “Recently Discovered Chinese Green Glazed Wares of the Thirteenth and Fourteenth Centuries in Singapore and the

Riau Islands,” in New Light on Chinese Yue and Longquan Wares. Archaeological Ceramics Found in Eastern and Southern Asia,

A.D. 800-1400, ed. Ho Chuimei (Hong Kong: The University of Hong Kong, 1994), p. 229-50.

19

�lakawood, the settlement also functioned as an ‘entrepȏt’ which was supposedly heavily

involved in economic ‘exchanges at the sub-regional level’ encompassing Sumatra, the lower

portion of the Malay Peninsula and Java. Heng also consolidated the primary features of Bān

Zú’s urban layout from these sources, namely a ‘Royal Residency,’ ‘Ritual District,’ ‘Royal

Garden,’ ‘Servants and Artisans District,’ ‘Orang Laut (sea nomads or gypsies) Settlement Area’

and a ‘Foothill Plain/Commonalties District,’ which he then mapped on a reconstructed plan of

pre-colonial Singapore. 83 While the archaeological record was consulted, it was used primarily

as a visual illustration of Bān Zú’s material culture, but not in his formulation of the

abovementioned settlement’s different districts which was inferred entirely from historical

textual sources. Most recently, Heng together with Kwa Chong Guan, and Tan Tai Yong

presented a 700-year history of Singapore by claiming Temasek-Singapura as the natural

predecessor of the present nation-state of Singapore in the longue durée, thereby drawing close

parallels between the island’s past as a ‘thriving emporium’ and its present status as a ‘global

city in the post-Cold War cycle of globalization.’ 84

CHAPTER SUMMARIES

Although much ink was spilled in the first two historiographical phases of Singapore’s

pre-colonial history, a very disproportionately small amount of knowledge about the settlement

has been attained. Nonetheless, an amalgamation of hypotheses primarily centred on disparate

textual sources – a ‘Temasek Paradigm’ – has emerged as the current framework of analysis

governing the study and understanding of pre-colonial Singapore in the present

historiographical phase. More importantly, the recovery of new material cultural evidence of

pre-colonial Singapore from recent archaeological excavations now provides an invaluable

opportunity to verify the underlying narrative set in this paradigm: was pre-colonial Singapore

a complex port-city in the 14th century as suggested in various historical sources? What more

83

Derek Heng Thiam Soon. Temasik: Reconstruction of a Classical Period Malay Trading Port Polity. M.A. Thesis. University

of London, 1997; see also Heng, “Temasik as an International and Regional Trading Port in the Thirteenth and Fourteenth Centuries:

A Reconstruction based on Recent Archaeological Data,” JMBRAS 72,1 (June 1999), p. 113-24; Heng, “Reconstructing Banzu, A

Fourteenth Century Port Settlement in Singapore,” JMBRAS 75,1 (June 2002), p. 69-90.

84

Kwa Chong Guan, Heng, Tan Tai Yong, Singapore. A 700-Year History (Singapore: National Archives of Singapore, 2009), p.

vii, 9-52.

20

�can we learn about this settlement and its inhabitants, and what implications will the results of

archaeological analysis have on this paradigm? To do anything otherwise risks rendering the

results and arguments of further historical research meaningless if and when contradicting

archaeological finds are recovered in the future.

Hence, Chapter 2 will summarize and present the Temasek Paradigm as well as various

elements of settlement complexity according to textual sources contemporaneous to the

settlement. A review of key interpretations of these sources by various scholars will also

illustrate their limits in providing a conclusive picture of pre-colonial Singapore and hence,

highlight the need for incorporating more archaeological data and analyses in the study and

reconstruction of this settlement. Chapter 3 presents the wealth of information derived from

archaeological data. Besides showing that STA was a pre-colonial archaeological site

contemporaneous to the polity of Temasek-Singapura as mentioned in various historical

sources, the non-random variation in the distribution of sampled artefacts and evidence of craftspecialization at the site will also demonstrate the presence of complex organization in precolonial Singapore. This intra-site analysis will provide historians and archaeologists alike the

first time an insight to the nature of pre-colonial Singapore’s spatial organization, which will

be a first for any Southeast Asian settlement site in this period. In conclusion, the level of

settlement complexity derived from archaeological sources will be evaluated against that

already established in the paradigm to create a much more comprehensive and plausible picture

of 14th century Singapore.

21

�II.

TEMASEK-SINGAPURA:

THE PARADIGM AND ITS SOURCES

This, then, is not an indictment of evidence but

of methodology: of the way data has been assessed

and used to conform to a preconceived theory.

Michael A. Aung-Thwin, 2005. 1

This chapter begins by asking a simple yet fundamental question: What was precolonial Singapore? As seen in the previous chapter, various scholars have directly or indirectly

answered this question in their attempts to historicize the island’s misty past. Consequently,

their collective work has coalesced into the present conceptualization of pre-colonial Singapore

as the site of the elusive polity of Temasek-Singapura. The present thesis refers to this

conceptualization as the ‘Temasek Paradigm,’ one which serves as a theoretical and

philosophical framework for the study of pre-colonial Singapore. In many respects, the

paradigm and its historical sources suggest that pre-colonial Singapore – as Temasek-Singapura

– was a highly complex, hierarchical and socially-stratified society built on the economic

foundation of both regional and international maritime trade. However, to paraphrase Michael

A. Aung-Thwin’s quote, it is not the validity of these sources that is interrogated here, but rather,

that of their interpretations by respective scholars which have led to the formulation of this

conclusion within the paradigm.

THE PARADIGM

The paradigm’s conceptualization of pre-colonial Singapore is best enunciated by the

most recent works of local scholars seeking to shift the writing of a histoire événementielle of

1

Michael A. Aung-Thwin, The Mists of Rāmañña. The Legend That Was Lower Burma (Honolulu: University of Hawai‘i Press,

2005), p. 3.

22

�Singapore, conventionally beginning with the arrival of the British in 1819, to that of the

island’s settlement history in la longue durée. Seeing ‘the past in Singapore’s present,’ Heng

identified ‘Temasik’ as a ‘Malacca Straits region port-polity’ and the ‘first documented

settlement to exist on Singapore Island.’ Temasek-Singapura is hence situated as the first of

five key phases in the island’s settlement history; followed by Singapore as part of the Melaka

and Johor Sultanates between the 15th and 17th centuries; next as an East India Company factory

in the 19th century; then as a Crown Colony and administrative centre of British Malaya until

1963; then part of the Malaysia which ended in 1965; and finally as the present independent

nation-state of Singapore. In the process, Heng highlighted features such as ‘political

autonomy,’ ‘existence of core and non-core groups,’ ‘having to make local products available

for export,’ ‘absence of a geographical hinterland,’ ‘economic sphere limited to Johor and Riau’

and ‘extent of economic sphere dictated by larger/regional contexts’ as recurring patterns of

Singapore’s settlement history governed by the ‘historical experiences and constraints’ of its

geographical location in the Melakan Straits region. 2

Following Heng’s call for the integration of Temasek-Singapura into the island’s precolonial past, a textbook entitled Singapore. A 700-Year History. From Early Emporium to

World City was published by the National Archives of Singapore to spearhead ‘a

comprehensive re-telling of the Singapore story from a local perspective.’ Co-authored by Heng,

Temasek-Singapura is advanced again as the natural predecessor of the present nation-state of

Singapore in the longue durée, thereby drawing close parallels between the island’s past as a

‘thriving emporium’ and its present status as a ‘global city in the post-Cold War cycle of

globalization.’ Calling for a ‘long-sighted view of Singapore’s past,’ the settlement is posited

to be both a thriving port of trade and the capital of a Malay polity in a post-Srivijayan world

that struggled to maintain its autonomy vis-à-vis Majapahit and ‘Siamese’ hegemony. At the

same time, the emergence of Temasek-Singapura as a port of trade is now situated within the

2

Heng, “Indigenising Singapore’s Past: An Approach towards Internalising Singapore’s Settlement History from the Late

Thirteenth to Twenty-First Centuries,” in New Perspectives and Sources on the History of Singapore, ed. Heng (Singapore:

National Library Board, 2006), p. 15-27.

23

�context of the rise of multiple autonomous Southeast Asian ports – a result of the increase in

Chinese trading activity and the decline of Srivijayan hegemony along the Straits of Melaka –

that participated in the Asian maritime economy between the 11th and 14th centuries. Its primary

function, the authors argued, was to serve as a ‘collection centre’ and ‘export gateway’ for

indigenous products between ‘the immediate hinterland of the Riau Archipelago and South

Johor’ and ‘the wider Asian maritime economy,’ specifically that of the South China Sea.

‘Unique’ commodities such as lakawood, hornbill casques, cotton and elephants were quoted

as the primary exports from its port. Consequently, the settlement is postulated to exist

sometime between the end of the 13th century, ‘emerged as a prosperous emporium that catered

mainly to the Chinese market’ by the mid-14th century and met its demise as a significant trade

centre with the establishment of Melaka in the 15th century. 3

As a result of the supposed Palembang origin of Temasek-Singapura’s first ruler as