Chelsea Clinton first heard that Joe Biden was stepping down and throwing his support behind Kamala Harris to be the Democratic nominee for president from her husband, Marc Mezvinsky. Clinton was playing outside with her three kids and ignored a text. When he followed up with a phone call, she knew something was up. “I have to give my husband credit,” she says. “I heard from my husband before Apple News told me.”

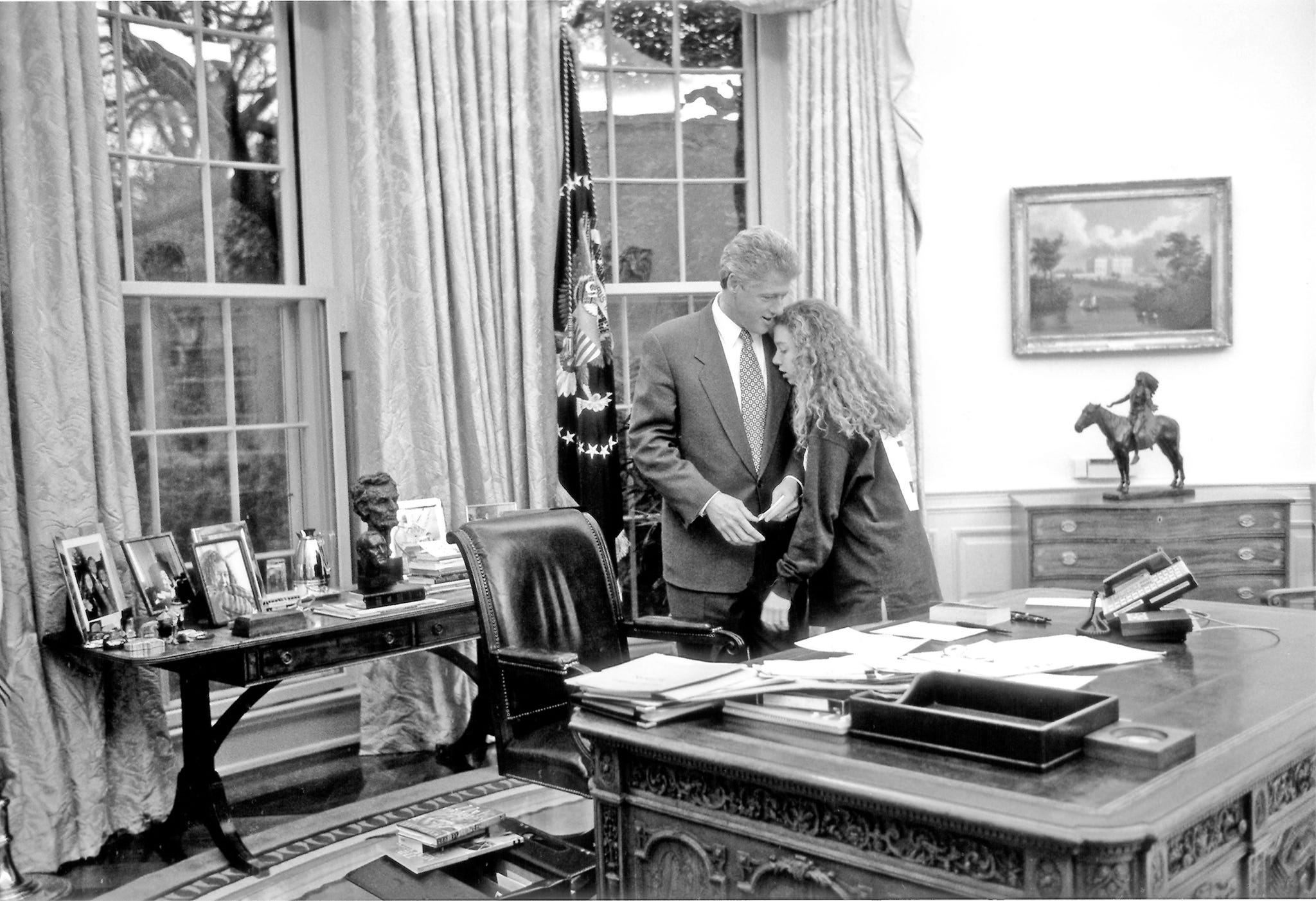

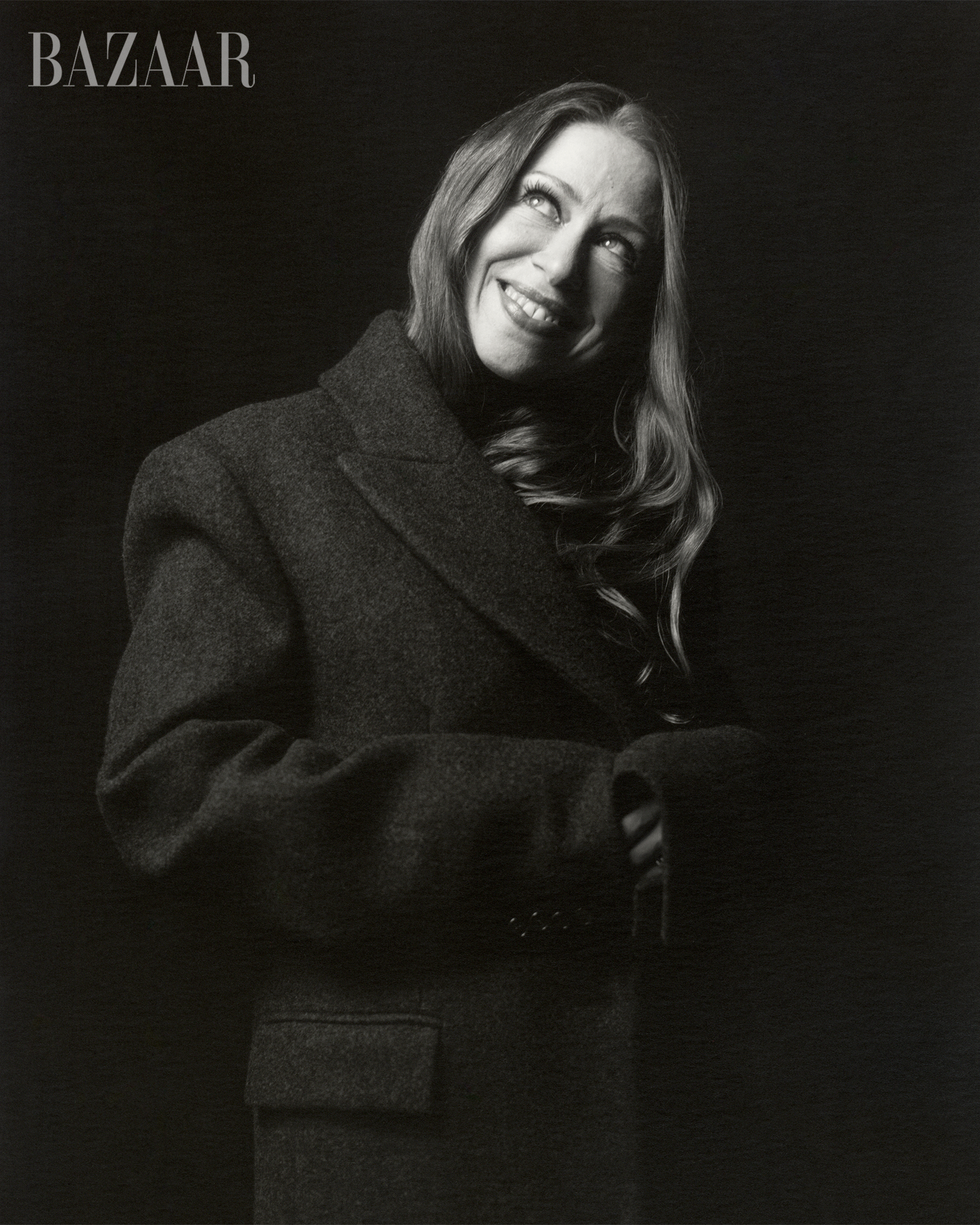

Clinton and I connected initially to discuss her work around health equity. At the Clinton Foundation, where she works alongside her father, former president Bill Clinton, and her mother, former Secretary of State, senator, and presidential nominee Hillary Rodham Clinton, she has focused on women’s healthcare, particularly reproductive rights, as well as supporting young families whose lives have been impacted by the effects of climate change. Clinton is a part of this year’s Icons portfolio in recognition of that work, and for the way she has carved her own path, when, as the only child of one of America’s most preeminent political families, her future may have otherwise seemed preordained. In addition to her work with the foundation, she is also a best-selling children’s book author, with her popular She Persisted series highlighting the achievements of women around the world.

We are on the phone again because Clinton wants to express her support for Harris. She does this in the kind of polished way you might expect from someone who has spent much of her life with either parent running for or holding the highest office in the land. “I feel incredibly excited in my heart by the prospect of having a woman president and that woman president being Kamala Harris,” she tells me. “I think Kamala Harris is exactly the person that we need for this moment.” She ticks off Harris’s qualifications—chief among them, she says, that the vice president has “arguably been our leading messenger on reproductive rights and freedom, making the argument that full reproductive healthcare access and the ability for women to make the choices that we know are right for ourselves, our futures, our families, is both a matter of individual rights but also a fundamental freedom that we have a right to in this country,” she explains. “I don’t think it’s being discussed efficiently in the current conversation about her.”

I imagine, though, that, having seen her own mother subjected to vicious, sexist attacks after breaking the ultimate glass ceiling, as the first woman to secure the nomination of a major political party when she ran for president against Donald Trump in 2016, Clinton’s feelings may be more complicated (or more personal, at least). Is she apprehensive about watching another woman run as the Democratic nominee against Trump? About the swell of misogyny and racism that will be unleashed? Is this a glass cliff rather than another glass ceiling?

“I have no doubt that the completely baseless sexist, misogynistic, racist talk that we’ve seen already will continue and grow over the next, now—goodness—less than three months, until Election Day,” Clinton says. “And yet, I hope that we are more well-equipped to recognize them, and to defang them, and to not share them, and to stand up against them with facts, and evidence, and kindness, and joy. I think that in general, people are much more aware now of the different ways in which social media can be and has been weaponized, especially against women elected officials.”

She is unwavering in her optimism. “I’m really so proud of when my mom ran in 2016,” she says. “And I believed then that we could elect a woman president.” Clinton adds: “She did win three million more votes than Donald Trump.”

Clinton’s optimism can at first come off like a tic, a reflexive reaction to having spent most of her life in the public eye and, later, campaigning with her mother, always on message. It is also, she explains, part of how she was raised. “I grew up in an optimistic family, where my parents were constantly working to try to make the world better, whether that was our home state of Arkansas or at the national level or at a global level,” she says. “And there was inherent optimism in that. They wouldn’t have worked so hard if they didn't believe that their energies and their endeavors and the people they could bring together couldn’t make life better and more just and equitable. So I think it was impossible for me to then not have believed ‘Well, what can I do?’ as an important motivating question of my life. ‘What should I do? What must I do?’ ”

Clinton accurately senses my wariness of her upbeat mindset. She tells me later, in a way that makes me reconsider my easy default to cynicism or despair, “I think optimism, candidly, is a moral choice. And I think that cynicism is the great preserve of the people who want to protect the status quo. I think one of the greatest resources the patriarchy has is cynicism, and trying to convince people that nothing can change, because it doesn’t want anything to change. I believe things can change, and I believe a lot has changed since 2016.”

Right now, an urgency and a righteous rage have been driving Clinton in her fight for reproductive rights. When we speak about what health care looks like for women in states where abortion access has been banned—including in her home state of Arkansas—her measured tone picks up a bit. “I’m incredibly angry that as of January, [since Roe was overturned], 65,000 women and girls in this country have been forced to give birth to their rapists’ children,” she says. “I’m incredibly [angered] by the ceaseless drumbeat of stories of women being forced into sepsis. Or they’re provided the medical care that their doctors have known for days, or sometimes even weeks, that they would need— but because 'only' their health and not their baby’s life was in danger, they had to wait until death would be all but certain before an abortion [was] provided. That makes me just so furious, like vibrating-with-anger furious.”

While these issues were always important to Clinton, they took on a visceral urgency after she became a mother herself. “It became more of a physical feeling when I became a parent, in a way that I wasn’t expecting. I believed, because I’d heard my friends or my mom talk about it, about how your heart expands, and really lives outside your body. And I’d had all of those experiences immediately when Charlotte was placed on my chest after she was born.” Charlotte Clinton Mezvinsky was born in 2014; her brother Aidan was born in 2016, and Jasper in 2019. “I hadn’t expected, though, to physically feel this reverberating sense of ‘Why are we making mothers more imperiled? Why are we making it more dangerous to be pregnant and to give birth and to be a new mom in America in the 21st century?’ ” she says. “What motivates me most is both the hope and the fear of the world today for my children, and how unacceptable so much of what I see is for them and for their generation.”

Clinton has never declared her intent or made overtures about joining the family business when it comes to running for office. But I leave our conversations feeling like she’d be pretty good at it. I try, mostly fruitlessly, to get a glimpse of the real person behind the impassioned talk, in the brief hour and change we collectively have together. At the end of our first meeting, over Zoom, I ask her to describe where she is. She has her background blurred, I assume for security reasons. She’s in Wyoming, she tells me, with her kids and her parents, visiting nearby national parks. Never mind that I’ve clearly interrupted her vacation. She finds a way to circle back to optimism: “We’re deep into different conservation stories about how we brought back the American bison and the bald eagle,” she explains. “Those too, I think, are also important stories of optimism for our kids and what’s possible when we set the goals and we move determinedly toward them.”

I ask her what else she is doing today. She holds up some sticky notes with to-do lists scrawled on them; haphazard lines cordon off each item. “I love sticky notes,” she tells me. “I also have different colors of my sticky notes.” “So there’s a system?” I ask. She takes a breath. “So the things I hope to get done exist in blue and green, and things I have to get done exist in yellow or orange. It’s not the most brilliant schematic, I know, or insightful, probably, but it’s what works for me. And I also still have a notebook and I put the sticky notes in the notebook and my family makes fun of me, but it’s a system that works for me.” The haphazard but efficient system, Clinton's unnecessary justification of it; it's a pose and a way of working that I think a lot of moms can relate to. I tilt my computer camera toward my desk, which is also covered in sticky notes.

Hair: Joey George for Oribe; makeup: Janessa Paré for Chantecaille; manicures: Honey for Un/Dn Laqr; production: Block Productions; set design: Kadu Lennox.