The Long Beach/Fort Lauderdale relative risk study

2009, Journal of Safety Research

…

8 pages

1 file

AI-generated Abstract

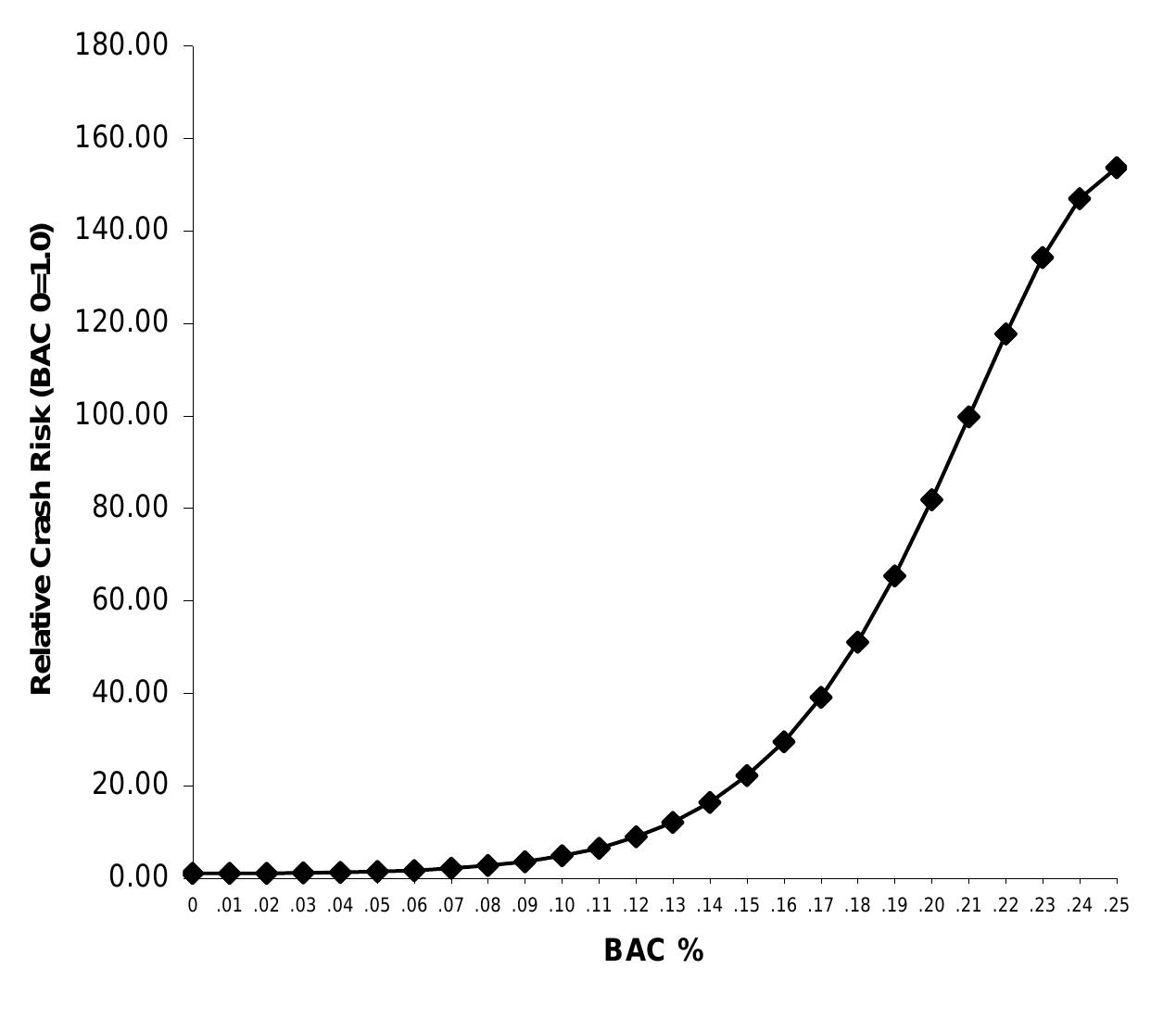

This study updates the relative risk associated with alcohol consumption and driving, using data collected from a case-control study in Long Beach, California and Fort Lauderdale, Florida. A total of at least 1,300 crash samples were analyzed, showing a dose-response relationship between Blood Alcohol Concentration (BAC) levels and crash risk, particularly increasing significantly at BACs above 0.04%. Statistical analyses included logistic regression to derive relative risk curves, providing insights into the dangers of driving under the influence of alcohol.

Sign up for access to the world's latest research

Related papers

Transportation Research Part E: Logistics and Transportation Review, 2005

A method is presented for estimating the risk of driver involvement in injury crashes for case-control data where control drivers have reliable measures of BAC (blood alcohol concentration) and other driver characteristics, but crash-involved drivers do not have BAC measures. The usual estimates of risk associated with BAC derived from case-control studies depend on the provision of driver BAC for virtually all case (crash-involved drivers) and control (drivers on the road) samples. The method described here makes use of the case-control study design but requires only the total numbers of case drivers within groups of drivers defined by variables common to both samples. The risk associated with BAC of New Zealand driver night-time involvement in injury crashes is estimated to illustrate the application of this method.

In order to determine the relative crash risk of drivers at various blood alcohol concentration (BAC) levels a case-control study was conducted in Long Beach, CA and Fort Lauderdale, FL. Data was collected on 4,919 drivers involved in 2,871 crashes of all severities. In addition, two drivers at the same location, day of week and time of day were sampled a week after a crash, which produced 10,066 control drivers. Thus, a total of 14,985 drivers were included in the study. Relative risk models were generated using logistic regression techniques with and without covariates such as driver age, gender, marital status, drinking frequency and ethnicity. The overall result was in agreement with previous studies in showing increasing relative risk as BAC increases, with an accelerated rise at BACs in excess of .10 BAC. After adjustments for missing data (hit-and-run drivers, refusals, etc.) the result was an even more dramatic rise in risk, with increasing BAC that began at lower BACs (abov...

1999

Because many fatal crashes involve more than one vehicle, the actual fraction of drinking drivers involved in these crashes is lower than the values cited above. Overall, roughly 30 percent of drivers in fatal crashes have been drinking, with that percentage rising to 50 percent during peak alcohol usage times. 2 There is also survey data asking drivers whether they have driven when they have "had too much to drink" (Liu et al 1997). In addition to any question about the accuracy of the responses given, these surveys have not attempted to ask drivers to report the percentage of miles driven with and without the influence of alcohol. Without that number, accurate estimates of the elevated risk of drinking drivers cannot be computed.

Annals of advances in automotive medicine / Annual Scientific Conference ... Association for the Advancement of Automotive Medicine. Association for the Advancement of Automotive Medicine. Scientific Conference, 2009

Alcohol involvement in fatal crashes (any driver with a blood alcohol concentration [BAC] = .01g/dL or greater) in 2007 was more than three times higher at night (6 p.m.-6 a.m.) than during the day (6 a.m.-6 p.m.) (62% versus 19%). Alcohol involvement was 35% during weekdays compared to 54% on weekends. Nearly one in four drivers (23%) of personal vehicles (e.g., passenger cars or light trucks) and more than one in four motorcyclists (27%) in fatal crashes were intoxicated (i.e., had a BAC equal to or greater than the .08 g/dL illegal limit in the United States). In contrast, only 1% of the commercial drivers of heavy trucks had BACs equal to .08 g/dL or higher. More than a quarter (26%) of the drivers with high BACs (>or=.15 g/dL) did not have valid licenses. The 21- to 24-age group had the highest proportion (35%) of drivers with BACs>or=.08 g/dL, followed by the 25- to 34-age group (29%). The oldest and the youngest drivers had the lowest percentages of BACs>or= .08 g/dL...

Alcoholism and psychiatry research, 2013

INTRODUCTIONRoad traffic injuries have become a global developmental and health issue. The likelihood of accidents in general and accidents with fatal outcomes may depend on a large number of factors. Some among these are the condition of roads, the number of vehicles on the roads, population size, population density, economic situation,1"2 the percentage of young drivers3 in traffic, while some relate to the characteristics of the drivers and the manner of driving. Thus, the researchers found out that the economic growth results in the increase of the number of registered vehicles,1"2 i e. vehicles that are in use and consequently in a larger number of road accidents. With regard to road accidents with fatal outcome, some authors observed their decrease and others increase2 linked to the economic growth. Bener and Crundall4 conclude that the number of accidents with fatal outcome decreases with the growth of the number of vehicle owners. They associate it with the lower n...

Journal of studies on alcohol and drugs, 2012

The purpose of this study was to determine whether the relative risk of being involved in an alcohol-related crash has changed over the decade from 1996 to 2007, a period during which there has been little evidence of a reduction in the percentage of all fatal crashes involving alcohol. We compared blood-alcohol information for the 2006 and 2007 crash cases (N = 6,863, 22.8% of them women) drawn from the U.S. Fatality Analysis Reporting System (FARS) with control blood-alcohol data from participants in the 2007 U.S. National Roadside Survey (N = 6,823). Risk estimates were computed and compared with those previously obtained from the 1996 FARS and roadside survey data. Although the adult relative risk of being involved in a fatal alcohol-related crash apparently did not change from 1996 to 2007, the risk for involvement in an alcohol-related crash for underage women has increased to the point where it has become the same as that for underage men. Further, the risk that sober underag...

Psychopharmacology, 2013

Rationale: Alcohol is the most frequently detected substance in fatal automobile crashes, but its precise mode of action is not always clear. Objective: The present study was designed to establish the influence of blood alcohol concentration as a function of the complexity of the scenarios. Road scenarios implying automatic or controlled driving performances were manipulated in order to identify which behavioral parameters were deteriorated. Method: A single blind counterbalanced experiment was conducted on a driving simulator. Sixteen experienced drivers (25.3 ± 2.9 years old, 8 men and 8 women) were tested with 0, 0.3 g/l, 0.5 g/l and 0.8 g/l of alcohol. Driving scenarios varied: road tracking, car following and an urban scenario including events inspired by real accidents. Statistical analyses were performed on driving parameters as a function of alcohol level. Results: Automated driving parameters such as standard deviation of lateral position (SDLP) measured with the road tracking and car following scenarios were impaired by alcohol, notably with the highest dose. More controlled parameters such as response time to braking and number of crashes when confronted with specific events (urban scenario) were less affected by the alcohol level. Conclusion: Performance decrement was greater with driving scenarios involving automated processes than with scenarios involving controlled processes.

Neuro endocrinology letters, 2011

Operator's movements are one of the areas where variability is undesirable. Vehicle driving is probably the most frequent operator movement in society where errors can result in serious social, medical and economic consequences. In this article we focused on the influence of moderate alcohol intoxication (less then 1.0 g/kg) on right hand movement variability during manual gear selection and on driving ability. The test took place in a laboratory setup in a passenger vehicle simulator. Simulated traffic lights were used to stop the car and hand movement was measured by kinematical analysis with the use of a motion capture system. Large variability in blood alcohol concentrations were observed as well as large intra-individual hand movement variability and reaction time to visual stimulus. The findings are somewhat ambiguous. Research outcomes did not confirm the hypothesis about the impact of moderate alcohol intoxication on movement variability. On the other hand, in some cases...

Annual proceedings / Association for the Advancement of Automotive Medicine. Association for the Advancement of Automotive Medicine, 2006

Twenty years ago the American Medical Association reported the relationship between blood alcohol concentration (BAC) and crash causation. This study addresses culpability, age, gender and BAC in a population of drivers injured in motor vehicle crashes. Five years of hospital and crash data were linked, using probabilistic techniques. Trends in culpability were analyzed by BAC category. Given BAC level, the youngest and oldest drivers were more likely to have caused their crash. Women drivers had significantly higher odds of culpability at the highest BAC levels. Seatbelt use was also associated with culpability, perhaps as a marker for risk-taking among drinkers.

Annals of Emergency Medicine, 2011

Related papers

Analytical Biochemistry, 2010

Intelligence, 2004

Aquaculture International, 2013

Journal of neurovirology, 2009

TRANSSTELLAR JOURNALS, 2018

Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 2006

AIDS and Behavior, 2013

IOSR Journals , 2019

Journal of ship production and design, 2022

arXiv (Cornell University), 2010

Colloids and Surfaces A: Physicochemical and Engineering Aspects, 1998

IFAC-PapersOnLine, 2020

Ciência Rural, 2013

Journal of Clinical Microbiology, 2001

Scientific Reports, 2017

Raymond Peck

Raymond Peck