Papers by Benjamin Gehres

Many aspects can motivate the diffusion of ceramics, both in terms of the ‘chaîne opératoire’; th... more Many aspects can motivate the diffusion of ceramics, both in terms of the ‘chaîne opératoire’; the complexity

of the realisation, the time and energy invested in the making of the object; but also by its use, ornamentation, form or

content. However, new research on the raw materials used in the ceramics of the Armorican massif (western France)

has demonstrated the distribution of specific types of pastes (the result of the alteration of the crystalline base) over

distances superior to those observed for potteries shaped from common clay. These raw materials are characterised by

their rarity and by the presence of mineral inclusions conferring particular physical and mechanical properties to the

ceramics, such as better resistance to thermal shocks, a more homogeneous diffusion of heat or even greater impermeability.

Taking these observations into consideration, can ceramics be exchanged in relation to the use of a specific raw

material, and in this case, be considered as a value-added object and thus exchanged as such as is the case for lithic

artefacts such as jadeite axes, or even variscite beads and pendants?

In order to develop new research prospects centred around the production and diffusion of ceramics in western France,

the results of the petrographic studies of the potteries of several occupations located on the Armorican massif and dating

from the Late Neolithic (3800–2800 BC) and the Late Iron Age (450–50 BC) will be presented. This massif has the

particularity of being composed of a great diversity of magmatic and metamorphic rocks, such as granite, micaschiste

or gabbro, and the potters had at their disposal a multitude of types of clay. These raw materials possess mineral

inclusions having physical and mechanical characteristics, which can influence the quality of the pastes. For the Late

Neolithic, we observed the privileged diffusion over more than 50 km of ceramics shaped using clays containing the

alterations of talcschistes, which are only found on the island of Groix (Morbihan). These exchanged ceramics have

been found on sites with specialised activities, such as Saint-Nicolas-des-Glénan (Glénan Archipelago, Finistère) and

Er Yoh (Houat Island, Morbihan). The vessels are characterised by an abundance of sheaves of talc within their pastes,

giving the containers a greater impermeability, and blue amphibole grains, confirming that the island of Groix is the

origin of the raw material. The status of value-added goods has an influence on the management of the raw materials

and pottery production. Indeed, we can argue that the ceramics of this period were produced in the household and were

distributed within family units or at a community level to meet subsistence needs. However, what about the potteries

made with specific raw materials and used in exchange systems to obtain other value-added goods? Do they originate

from different production systems such as specialised workshops, or do they originate from domestic units and then

pooled for exchange? Also, how were the resources controlled, but only part of the population or was it a self-service?

During the Late Iron Age, several specialised pottery workshops appeared in areas where unusual raw materials such

as the gabbroic massifs of Saint-Jean-Du-Doigt (Finistère) and Trégomar (Côtes-d'Armor) were found. Their ceramics

are characterised by a large quantity of amphibole grains, and the paste of these vessels possesses a better diffusion of

heat and a greater resistance to thermal shocks. Finally, potters also exploited the alteration products of the serpentinite

deposits of Ty-Lan (Finistère), whose so-called proto-unctuous vases were recognised by a soft and soapy feel, but also

by the large amount of talc inclusions within them, giving them greater impermeability. These production areas distribute

their ceramics, most often shaped locally and for domestic use, over several tens or even hundreds of kilometres,

far beyond the other types of vessels. Furthermore, the greater the distance between the source of raw material and the

final destination of the vases, the more these ceramics are discovered in ritual rather than domestic contexts. This is the

case on the sites of Mez Notariou (Ouessant island, Finistère), Karreg Ar Skariked (Finistère) or the Moutons island

(Finistère).

Furthermore, the use of clay with superior physical and mechanical characteristics has been documented since the

beginning of the Neolithic period on the Armorican massif. This perpetuation in the use of these raw materials tends

to show that craftspeople quickly understood the interest of these raw materials and sought out such clays. Moreover,

it is rare to observe in this region such practices for the other clayey raw materials, whose sources are more common

and numerous.

It seems, therefore, that as in the case of lithic materials, uncommon clays acquire a different status according to their

physical and mechanical quality, as well as their remoteness from the deposit. In this paper, we propose to engage in a

reflection on the raw material used to shape ceramics as one of the factors that determine the diffusion of these products.

Finally, the criteria by which consumers could "identify" the raw materials used, not easily differentiated by the

naked eye, need to be defined. We can assume that the reputation of the fencers and/or potters could be an important

criterion based on an established trust between the consumer and the producer. However, the mass of the vessel and its

soapy feel, in particular for pottery with talc inclusions would also have been used to determine quality. This problematic

needs to be explored further, notably by studying pottery discovered in ritual contexts and tombs but also in areas

where other prestigious artefacts were produced (such as the Grand Pressigny region). It will thus be possible to reach

a greater understanding of the circulation of ceramics but also to shed new light on the occupations where these types

of vases are found.

L’étude pétrographique et géochimique de céramiques découvertes dans la zone atelier de fabricati... more L’étude pétrographique et géochimique de céramiques découvertes dans la zone atelier de fabrication d’anneaux en lignite du site portuaire de la Batterie-Basse à Urville-Nacqueville (Manche) a permis d’observer l’utilisation de plusieurs matières premières régionales pour façonner les poteries du site. De plus, l’importation de terres cuites a pu être mise en avant, depuis la zone atelier de Saint-Jean-du-Doigt (Finistère) à plus de 180 km et depuis la région de la plaine de Caen. Un groupe de pâte domine largement le corpus, caractérisé par une tradition technique particulière dans la préparation des pâtes des terres cuites, le rajout de coquilles broyées aux terres. En effet, des analyses pétrographiques, complétées par une approche par spectrométrie de masse à source plasma, couplée à un système d’ablation laser des inclusions bioclastiques, ont démontré que ce dégraissant ne correspond pas à des fossiles présents naturellement dans les argiles, mais que les potiers ont ajouté à leurs matières premières des fragments de coquilles préalablement broyées. Il s’agit d’une tradition qui n’est pour l’instant pas connue autre part au second âge du Fer dans l’Ouest de la France, et il faut se tourner vers les côtes anglaises pour identifier des procédés similaires. Il en va de même pour plusieurs autres pratiques observées sur le site de la Batterie-Basse, dont les racines pourraient se trouver de l’autre côté de la Manche.

The Exploitation of Raw Materials in Prehistory: Sourcing, Processing and Distribution, 2017

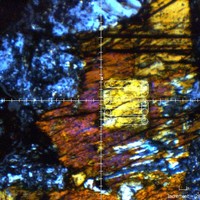

The punctual analysis of non-plastic inclusions by LA-ICP-MS in

ceramics pastes opens a new path... more The punctual analysis of non-plastic inclusions by LA-ICP-MS in

ceramics pastes opens a new path in the determination of the origins of

raw materials. Indeed, by this method it is possible to distinguish different

clay sources in cases when traditional methods (petrographic observation

and global chemical analysis) cannot. This approach is based on

comparisons of the chemical signatures of mineral inclusions present in

the pottery and the same mineral species in the mother rocks. This paper

will present advancements made in this field, in order to sensitize

archaeologists to this method that has only been slightly exploited and

which results can throw more light on micro-regional paleo-economic

problematics.

This article presents the latest methodological advances using the LA-ICP-MS technique for differ... more This article presents the latest methodological advances using the LA-ICP-MS technique for differentiating the origin of petrographically and chemically similar ceramic raw materials.

Based on several examples form the Armorican Massif (France), from a chronological period extending from the Neolithic to the Second Iron Age, we will see that the comparison of the chemical signatures of minerals included in fired clay with those from earth and source rocks

enables us to distinguish productions and to accurately trace the sources of the raw materials used by potters.

The analytical methods used for determining the origin of archaeological ceramics, such as petrog... more The analytical methods used for determining the origin of archaeological ceramics, such as petrography, X-ray powder diffraction, X-ray fluorescence spectrometry, attain their limits for differentiating bodies of similar composition, especially when they derive from the alteration of granitoid rocks. Our new approach is based on the chemical analysis of biotite inclusions in ceramic bodies using laser ablation-inductively coupled plasma-mass spectrometry, and enables us to identify the geological origin of the clay used. Spot analysis of the biotite inclusions contained in ceramics made from clay derived from the alteration of rocks can be linked to the original granitic massif. The thin section or rock analysis of biotite inclusions is relatively fast. The dosage of trace elements, such as lithium and vanadium establishes a filiation between the rocks and ceramics. Using this geochemical base, it is possible to establish a link between a granitic batholite and early ceramics and to propose a circumscribed production area. This article will focus on occupations located on islands from western France.

The analysis of ceramic raw materials, whether through petrographic observations of the inclusion... more The analysis of ceramic raw materials, whether through petrographic observations of the inclusions using a polarizing microscope or through general chemical analysis, may, in some cases, encounter difficulties related to the nature of the clay used by potters. This is particularly the case in the crystalline massifs, such as the Massif Central or the Armorican Massif, where the ubiquity of certain rocks such as granite or gabbro (weathered clays of which have been used by potters to make vessels) does not allow us to accurately identify the origins of the products. In fact, ceramics fashioned using granitic clays from locations several hundred kilometres apart, may have similar mineral inclusions and chemical signatures. The same is true for pottery made with rock alteration products such as gabbro and serpentinite, whose outcrops (although less numerous) may also cause doubt as to the exact geographical origin of the clays. These methodological obstacles curtail discussion regarding the exchanges which may have taken place between communities, and thus hamper our understanding of the relationships between human groups. It is, therefore, necessary to develop new approaches to the study of ceramic raw materials, in particular using tools such as the plasma mass spectrometer coupled with a laser ablation sampling system (LA-ICP-MS). This technique has allowed renewed studies of ceramic inclusions, as demonstrated by the work on the sourcing of fluvial shell tempers or the dating of detrital zircon inclusions using U/Pb methods. However, it also allows the sources of ceramic raw materials to be identified through analysis of the clay matrix, including mineral inclusions. This article presents the latest methodological advances made using the LA-ICP-MS technique for distinguishing the origin of ceramic pastes that are petrographically and geochemically similar. By means of several examples, located on the Armorican Massif and chronologically spanning the Early Neolithic to the Late Iron Age, we will demonstrate that some of the minerals included in these pastes can be used as tracers to differentiate between productions and to precisely identify clay sources and parent rocks. We will describe how the chemical composition of biotite tablets allows us to distinguish the origins of ceramics whose inclusions correspond to the mineral assemblage of granitic rock. Secondly, we will present the results obtained from the analysis of the biotites included in the clay paste of a Bronze Age urn discovered on Belle-Ile-en-Mer (Morbihan), an island whose geology does not feature granitic outcrops. This urn is, therefore, an import, which may have come from the neighbouring islands of Houat or Hoedic, or from the mainland. Next, we will present the results obtained from the analyses of amphibole grains included in pottery made from alteration clay derived from gabbroic rocks and we will see that this method allows us to identify and distinguish between two main pottery productions from workshops dating to the Late Iron Age. In fact, during this period in Brittany, two production areas used gabbroic clay to produce ceramics: these are located on two different gabbroic massifs, one at Trégomar (Côtes-d’Armor) and the other at Saint-Jean-Du-Doigt (Finistère). Their products were exported over several hundred kilometres, as far as the site of Hengistbury Head in southern England (Morzadec, 1995). However, until analysis of the amphibole grains using LA-ICP-MS, it was very difficult to identify the precise origin of the products.Furthermore, through the unique example of a Bronze Age ‘paléo-onctueuse’ ceramic discovered on the site of Kermenguy (Finistère), we will see that the singularity of a paste does not always allow us to identify its origin. This vessel was made with clay which derived from serpentinite, an ultra-basic rock, only two outcrops of which exist in Brittany: one located at Ty-Lan (Finistère) and the other at Belle-Isle-en-Terre (Côtes-d’Armor). However, since Kermenguy is equidistant from the two outcrops, it is difficult to identify the exact origin of the raw material used. Furthermore, clay from Ty-Lan was used by potters during the late Iron Age to make ‘proto-onctueuses’ ceramics. We will outline the results of the analyses of the opaque minerals present in the paste of the ‘paléo-onctueuse’ and ‘proto-onctueuse’ ceramics and in the two serpentinites, in order to identify their chemical signatures. In sedimentary basins, such as the Caen Plain, certain ceramic workshops may have existed that used clays derived from the decalcification of shelly limestone. These vessels are naturally tempered with fossil shells which are more or less cemented by limestone. This is one of the main clues permitting the origin of fossil shells to be determined. Examples of this type of pottery are common in the sedimentary basin of the Caen Plain, where Bronze Age and Early Iron Age potters produced pottery known as Caen Plain ware (Manson et al., 2011). However, in the case of shell-tempered pottery discovered in a crystalline massif we need to determine whether the inclusions are fossils shells derived from shelly limestone, or if the potters deliberately added crushed shells to their pastes. This is the case on the Late Iron Age site of La Batterie-Basse (Manche) where several ceramics containing crushed shell temper were found on the shore. We will see that the LA-ICP-MS can help us to determine the nature of these inclusions on the basis of their chemical compositions. Finally, the application of the methods presented in this article to ceramics from the Early Neolithic site of Kervouyec-Nevez (Finistère) provides us with an example of data crossover which can be obtained from analysis of several types of mineral inclusions. In fact, we will see that the inclusions within a section of wattle and daub can be used as a reference to determine the chemical compositions of several local minerals which can then be compared to the inclusions in the pottery discovered on the site.

Le quartier antique de Villa Roma à Nîmes (Gard), largement fouillé en 1991-1992, a révélé plusie... more Le quartier antique de Villa Roma à Nîmes (Gard), largement fouillé en 1991-1992, a révélé plusieurs domus ainsi qu’une unité originale (zone 12), au sein de laquelle plusieurs fours de potiers se succèdent ou coexistent tout au long du Ier s. ap. J.-C. Seul un groupe de trois fours, utilisé dans les années 20-40, peut cependant être sûrement associé à une production de céramiques, au sein de laquelle deux pâtes distinctes mais à dominante calcaire ainsi que vingt types de vases ont pu être distingués. La plupart se retrouvent en contexte domestique, mais certains présentent des caractéristiques, étayées par plusieurs comparaisons, qui incitent à les associer à des utilisations en contexte cultuel. Une présentation de l’évolution générale de la parcelle urbaine, avec argumentaires chronologiques, permet d’en mesurer la singularité – la fonction résidentielle semble ici peu présente –, à la suite de quoi est proposée une description précise de l’atelier et des vases produits. Cet exemple permet enfin de dresser un bilan des connaissances sur l’artisanat de la céramique à l’échelle de la ville de Nîmes, chef-lieu de la cité des Volques arécomiques.

Résumé :

L’étude de la céramique de la Batterie Basse dans la Manche a montré de nouveau que la ... more Résumé :

L’étude de la céramique de la Batterie Basse dans la Manche a montré de nouveau que la présence

de bioclastes dans les pâtes des céramiques de la Protohistoire est un phénomène très courant en

Normandie contrairement à la Bretagne, où en l’état actuel des connaissances, un seul individu daté

de l’âge du Fer a été décrit. Ces bioclastes, le plus souvent des fragments de bivalves, sont des éléments

non plastiques, soit présents naturellement dans les argiles sous forme de fossiles, soit sous forme de

coquilles contemporaines qui ont été pilées par les artisans afin de les incorporer dans leurs pâtes

pour modifier les caractéristiques techniques des argiles.

Ce travail a pour objectif de sensibiliser les archéologues à ce type de mobilier et d’évaluer les réponses

pouvant être apportées par les pétro-céramologues concernant l’origine de ces céramiques bien

spécifiques, autant par étude en lame mince, que par des analyses géochimiques. À travers l’étude

des différents sites de l’ouest de la France de l’âge du Bronze et de l’âge du Fer il s’agit également

d’étudier les échanges entre Bretagne et Normandie dans un premier temps, mais également de

mettre en lumière de possibles liens culturels à l’âge du Fer entre le continent, ici la Normandie, et

les îles britanniques.

Abstract:

The study of the ceramics from the site of the Batterie Basse in the region of Manche, shows again that the

presence of bioclasts in the clays of protohistoric ceramics is a very common phenomenon in Normandy

unlike in Brittany, where in the current state of knowledge only one individual from the Iron Age has been

described. These bioclasts, mostly fragments of bivalves, are non-plastic elements naturally present

in the clays, either in the form of fossils, either in the form of contemporary shells, or are incorporated

by the craftsmans after being pounded to modify the technical characteristics of the clays.

The aim of this work is to awareness the archaeologists to this type of artefacts and to evaluate

the response that could be brought by the petro-ceramologists concerning the origin of these very

specific ceramics, as per study thin blade, as geochemical analysis. Through the study of different

sites in western France, dating from the Bronze Age to the Iron Age, it is also possible to study the

interaction between Brittany and Normandy in a first time, but also to highlight possible cultural ties

to the Iron Age between the mainland, here the Normandy, and the British Isles.

Poster - 13th European Meeting on Ancient Ceramics (EMAC - 2015)

Actes du colloque de l'AFEAF 2013 , 2015

L’étude des populations insulaires de l’âge du Fer en Bretagne ainsi que leurs rôles dans les rés... more L’étude des populations insulaires de l’âge du Fer en Bretagne ainsi que leurs rôles dans les réseaux d'échange, de communication et de circulation des produits nécessite de connaître les relations qu’elles entretenaient avec le continent. Nous avons donc décidé d'étudier les céramiques découvertes sur ces îles pour connaître leurs origines et leurs déplacements et pour déterminer s'il s'agit de productions faites sur l'île où d'importations provenant du continent ou d'une autre île, afin de connaître le degré d'ouverture ou d'autonomie de ces occupations. Dans le cas de productions insulaires, la question d’un savoir-faire spécifique et indépendant de celui du continent sera posée. Existe-t-il des traitements spécifiques des inclusions (minérales ou autres) présentes dans les argiles sur les sites insulaires ? Les îles bretonnes étaient-elles incorporées dans une dynamique de commerce littoral ? Ce littoral jouait-il un rôle de frontière, éloigné des centres de productions et de pouvoir ou était-il lui-même un centre de production ? Pour cela les lots de céramiques étudiés proviennent de sites dont l'insularité est avérée à l'époque de l'occupation, c'est à dire qu'un passage par la navigation devait être obligatoire pour atteindre ces territoires.

Ces questionnements seront développés autour d'un type bien particulier de céramiques, appelées proto-onctueuses du fait de leur texture douce et savonneuse au toucher et dont la zone d'extraction de matière première est bien connue. Nous nous intéresserons plus particulièrement aux découvertes en contexte insulaire des sites de Karreg Ar Skariked (Cléden Cap-Sizun, 29) et de l'Île aux Moutons (Fouesnant, 29) et d'un îlot satellite de l'Île aux Moutons.

Afin de mettre en avant de nouvelles données pour répondre à ces problématiques, nous avons fait appel à plusieurs méthodes d'analyses archéométriques, qui se sont déroulées à différentes échelles d'observations et d'analyses en complément de l'étude typologique. Nous avons notamment étudié les inclusions non plastiques dans les pâtes servant à la confection des céramiques, permettant de reconnaître le type de roche dont est issue l’argile par les processus d’altérations ou encore des analyses chimiques globales et ponctuelles afin d'identifier des groupes de pâtes similaires ayant une même origine géologique et géographique. De telles analyses ont été réalisées sur un ensemble de sites de différentes périodes (allant du Néolithique à l'époque Gallo-romaine) dans le cadre d'une thèse. Nous présenterons notre réflexion concernant les sites de l'âge du Fer, qui voit notamment l'apparition en Bretagne de centres spécialisés dans le production de céramique, grâce à l’arrivée de nouvelles technologies comme le tour et plus tard le tour rapide qui permettra aux artisans de faire évoluer leurs productions, stylistiquement ainsi que quantitativement mais également vers des formes plus standardisées (Pierret 2001). Ces nouvelles techniques de production vont fournir aux artisans un gain de temps important qui modifiera les impératifs socio-économiques de l'époque, différents d’une production par moulage ou montage aux boudins.

DAIRE M.-Y., LE BIHAN J.-P., LORHO T., QUESNEL L., avec la collaboration de BAUDRY A., CHOISY-GUI... more DAIRE M.-Y., LE BIHAN J.-P., LORHO T., QUESNEL L., avec la collaboration de BAUDRY A., CHOISY-GUILLOU C., DREANO Y., DUPONT C., GEHRES B., LANGOUËT L., MOUGNE C., 2015 – Les modes d'occupation du littoral de la Bretagne continentale à l'Âge du Fer. Une première approche. In F. Olmer et R. Roure (eds.), Les Gaulois au fil de l'eau, Actes du 37e colloque international de l'AFEAF, 8-11 mai 2013, Montpellier – France, Vol. 1. Communications. Ausonius éditions, Bordeaux 2015, Mémoires 39, ISSN : 1283-2995, ISBN : 978-2-35613-129-4, 143-166.

À travers cette communication, les auteurs souhaitent présenter une première approche des modes d’occupation le long du littoral de la Manche et de l'Atlantique au premier millénaire avant notre ère. C'est l'occasion d'actualiser la vision du peuplement de l'Ouest de la France à l'âge du Fer où les occupations littorales ont parfois manqué dans certaines synthèses récentes.

Le cadre géographique retenu sera l'actuelle région administrative Bretagne qui présente 2700 km de linéaire côtier, si l'on inclut toutes les indentations des îles et du littoral continental. La longueur des côtes prises ici en compte permettra d'analyser les systèmes de peuplement à différentes échelles géographiques. Cette analyse repose sur une reprise critique de la documentation archéologique recensée sur cette partie du littoral, y compris les estuaires et rias qui en sont le prolongement naturel. Par ailleurs, cette contribution complète la synthèse consacrée dédiée aux îles bretonnes de plein océan (Le Bihan et al., ce volume).

Abstract / Résumé

The islands of the Glénan archipelago and Moutons Island (Fouesnant, Finistère... more Abstract / Résumé

The islands of the Glénan archipelago and Moutons Island (Fouesnant, Finistère) have been the subject of archaeological references since the eighteenth century and inventories in the early twentieth century, in which numerous indices of human presence at the end of Prehistory are mentioned. Researches drawn by Marthe and Saint-Just Péquart in 1926-27 confirmed the attractiveness of Neolithic and Gaulish people for these island areas. A rediscovery of these pioneering works and new exploration campaigns have resulted in a series of planned excavations, leading to the discovery of important set of constructions remains and objects. They show an almost continuous occupation, from the Mesolithic until the end of the Iron Age. Following a first major historiographical documentary work, the integration of the surveys data and of the multidisciplinary studies drawn after the recent fieldwork, fully completed for that is the Iron Age, are still in progress for the earlier periods; this allows to propose an initial assessment. The nature and function of the different sites have been identified and the important part played by these insular places could be considered in a renewed perspective. If discreet for the Palaeolithic period, the occupation of the Moutons Island and Glénan archipelago will intensify through the Neolithic and the Bronze Age, to become very dense at the end of the Iron Age. The perception of space seems to be is sometimes very different and sometimes strikingly similar. The marine submersion of the older sites can probably explain the low presence of hunter-gatherers on the islands, effective at the end of the Mesolithic. Still elusive because of the pending completion of analysis, the prehistoric Neolithic occupation is dense and characterized by the construction and use of megaliths and the development of specialized activities. The link with the neighbouring coastal communities is strong. It was not until the beginning of the Metal Ages to the occupation of the island territory is extensive. In the Bronze Age, the occupation of the entire complex Moutons-Glénan islands is effective and increases at the beginning of the first millennium, when the cemeteries occupy a large part of the archipelago. At the end of La Tène period, the Glénan and Moutons islands are densely occupied and could be integrated into a long-distance exchange networks. The strategic geographical position, on the one hand between the continent and the ocean and the other south of the tip of Brittany, gives them, from the Late Prehistoric time, a key role in the development of the Atlantic societies.

Résumé :

Les îles de l’archipel des Glénan et l’île aux Moutons (Fouesnant, Finistère) ont fait l’objet de mentions archéologiques depuis le XVIIIème siècle et d’inventaires au début du XXème siècle, dans lesquels est déjà mentionné un nombre important d’indices d’une fréquentation humaine dès la fin de la Préhistoire. Les recherches entreprises par Marthe et Saint-Just Péquart en 1926-27 confirmèrent l’attrait des hommes du Néolithique et des Gaulois pour ces espaces insulaires. Une redécouverte de ces travaux pionniers et de nouvelles campagnes de prospection ont donné lieu à une série de fouilles programmées, ayant permis la découverte d’importants vestiges immobiliers et mobiliers. Ils montrent une occupation quasi continue du Mésolithique jusqu’à la fin de l’époque gauloise. Suite à un premier important travail documentaire historiographique, l’intégration des données de prospections et des études pluridisciplinaires menées à l’issue des récents travaux de terrain, totalement achevée pour de ce qui est de l’Age du Fer, est encore en cours pour les époques antérieures, ce qui permet de dresser un premier bilan. La nature et la fonction des différents sites ont pu être précisées et la place importante de ces espaces insulaires remise en perspective. Très discrète au Paléolithique, la fréquentation de l’île aux Moutons et de l’archipel des Glénan va s’intensifier au Néolithique moyen et à l’Age du Bronze, pour devenir très dense à la fin de l’Age du Fer. La perception des espaces insulaires s’avère tantôt très différente, d’un contexte à l’autre, tantôt étonnamment similaire. La submersion des sites les plus anciens peut sans doute permettre d’expliquer la faible présence des chasseurs-cueilleurs sur l’île, effective dès à partir de la fin du Mésolithique. Encore difficile à appréhender dans l’attente de l’achèvement des analyses , l’occupation préhistorique néolithique est dense et se caractérise par la construction puis l’utilisation de mégalithes et le développement d’activités spécialisées. Le lien avec les communautés littorales voisines est fort. Il faut attendre les débuts des âges des Métaux pour que l’occupation du territoire insulaire soit extensive. A l’Age du Bronze, l’occupation de la totalité du complexe Glénan-Moutons est effective et s’accentue au début du 1er millénaire, où les nécropoles occupent un large territoire sur l’archipel. A la fin de La Tène, les Glénan et les Moutons sont densément occupés et pourraient s’intégrer au cœur de réseaux d’échanges à longue distance. La position géographique stratégique, d’une part entre le continent et l’Océan et, d’autre part, au sud de la pointe bretonne, leur confère depuis la fin de la Préhistoire un rôle déterminant dans le développement des sociétés atlantiques.

« SOMEWHERE BEYOND THE SEA » LES ÎLES BRETONNES : PERSPECTIVES ARCHÉOLOGIQUES, GÉOGRAPHIQUES ET HISTORIQUES, Mar 31, 2015

Résumé

Cet article vise à préciser la contribution de l’archéologie à l’étude des dynamiques ins... more Résumé

Cet article vise à préciser la contribution de l’archéologie à l’étude des dynamiques insulaires, sur la base de l’analyse de l’évolution culturelle et du peuplement (insularité vs contacts) combinée à des approches environnementales de l’évolution des paysages côtiers. D’un point de vue méthodologique, un tel processus est basé sur une approche interdisciplinaire couvrant plusieurs domaines tels que les campagnes de terrain (fouilles archéologiques et prospections systématiques), des études historiques pour les périodes plus récentes (textes), mais aussi, pour une part, le recours à la biologie et aux sciences de la terre. À titre d’illustration des questions développées dans le cadre géographique de la façade atlantique de l’Europe, les auteurs présentent les principaux résultats des enquêtes archéologiques de longue haleine menées sur l’île de Groix (Morbihan). Mettant l’accent sur l’une des plus grandes îles de l’Ouest de la France, aujourd’hui localisée à 5,5 km des côtes les plus proches, est peuplée depuis le début Préhistoire et les chercheurs peuvent y documenter l’évolution de la relation entre l’homme et l’environnement maritime (de l’exploitation des ressources à la navigation ...) à différentes échelles de temps, du début du Paléolithique jusqu’à l’époque Moderne.

Abstract:

This paper aims to discuss the contribution of archaeology to ancient island dynamics; this includes studying the cultural evolution and development of settlement (‘islandness’ vs. contacts), combined with environmental approaches dealing with coastal landscape changes. From a methodological point of view, such an archaeological process is based on an interdisciplinary approach covering several research fields such as prehistory and archaeology (excavations and systematic surveys), historical studies (texts), biology and the earth sciences.

As an illustration of the issues developed in the geographical context of the European Atlantic Arc, the authors present the main results of long-continued investigations on Groix Island (Brittany, France). Groix Island, which is situated 5.5 km from the nearest coast, is among the larger islands of Western France (1520 ha/15 km²) and has been populated since early Prehistory. Therefore, this island documents the evolution of the relationship between human groups and the maritime environment (resource exploitation, navigation, etc.) on various timescales from the early Palaeolithic up until to the Middle Ages.

« SOMEWHERE BEYOND THE SEA » THE ISLANDS OF BRITTANY : AN ARCHAEOLOGICAL, GEOGRAPHICAL AND HISTORICAL POINT OF VIEW, Edition: British Archaeological Reports, Publisher: Archeopress, Editors: Lorena Audouard, Gehres Benjamin, pp.pp. 34 - 45 , Mar 31, 2015

Résumé

Les analyses pétrographiques des céramiques nous permettent de connaître les origines géo... more Résumé

Les analyses pétrographiques des céramiques nous permettent de connaître les origines géologiques des matières premières et donc leurs lieux de production. Cette méthode, appliquée de manière diachronique à plusieurs occupations du complexe de Houat, Hoedic et de Belle-Île-en-Mer, nous fournit ainsi un aperçu des échanges et des liens qu’ont pu avoir ces populations avec leurs voisins : s’agissait-il d’îles formant des noeuds de communication et d’échange, ou des « cul-de-sac » ? Y-a-t-il eu des phases de repli et d’ouverture, et si oui, pouvons-nous les apercevoir sur ce laps de temps relativement long par le biais des seules productions céramiques ? L’évolution des techniques a-t-elle eu un impact sur l’évolution des échanges ?

Abstract

The petrographic analysis of ceramics allows us to trace the geological provenance of raw materials and thus their production sites. When applied diachronically to several occupations belonging to the complex group of Houat, Hoedic and Belle-Ile-en-Mer, this method provides an overview of exchanges and contacts that may have taken place between these island populations and their neighbours: did the islands form nodes of communication and exchange or do they represent dead-ends? Were there phases of retreat and opening up and, if so, can we see evidence for these changes over a relatively long time period by considering solely the ceramic productions? Did the evolution of technology have an impact on the development of trade?

Bulletin de l’ Association pour la promotion des recherches sur l’ âge du Bronze, 2015

Les textes présentés dans le bulletin de l'APRAB n'engagent que leurs auteurs, et en aucun cas le... more Les textes présentés dans le bulletin de l'APRAB n'engagent que leurs auteurs, et en aucun cas le comité de rédaction ou l'APRAB.

Large J.-M., Audouard L., Braguier S., Carrion Y., Delalande C., Deloze V., Donnart K., Gehres B., Hamon G., Joly C., Marcoux N., Mens E., Querré G., Visset L., 2014

Uploads

Papers by Benjamin Gehres

of the realisation, the time and energy invested in the making of the object; but also by its use, ornamentation, form or

content. However, new research on the raw materials used in the ceramics of the Armorican massif (western France)

has demonstrated the distribution of specific types of pastes (the result of the alteration of the crystalline base) over

distances superior to those observed for potteries shaped from common clay. These raw materials are characterised by

their rarity and by the presence of mineral inclusions conferring particular physical and mechanical properties to the

ceramics, such as better resistance to thermal shocks, a more homogeneous diffusion of heat or even greater impermeability.

Taking these observations into consideration, can ceramics be exchanged in relation to the use of a specific raw

material, and in this case, be considered as a value-added object and thus exchanged as such as is the case for lithic

artefacts such as jadeite axes, or even variscite beads and pendants?

In order to develop new research prospects centred around the production and diffusion of ceramics in western France,

the results of the petrographic studies of the potteries of several occupations located on the Armorican massif and dating

from the Late Neolithic (3800–2800 BC) and the Late Iron Age (450–50 BC) will be presented. This massif has the

particularity of being composed of a great diversity of magmatic and metamorphic rocks, such as granite, micaschiste

or gabbro, and the potters had at their disposal a multitude of types of clay. These raw materials possess mineral

inclusions having physical and mechanical characteristics, which can influence the quality of the pastes. For the Late

Neolithic, we observed the privileged diffusion over more than 50 km of ceramics shaped using clays containing the

alterations of talcschistes, which are only found on the island of Groix (Morbihan). These exchanged ceramics have

been found on sites with specialised activities, such as Saint-Nicolas-des-Glénan (Glénan Archipelago, Finistère) and

Er Yoh (Houat Island, Morbihan). The vessels are characterised by an abundance of sheaves of talc within their pastes,

giving the containers a greater impermeability, and blue amphibole grains, confirming that the island of Groix is the

origin of the raw material. The status of value-added goods has an influence on the management of the raw materials

and pottery production. Indeed, we can argue that the ceramics of this period were produced in the household and were

distributed within family units or at a community level to meet subsistence needs. However, what about the potteries

made with specific raw materials and used in exchange systems to obtain other value-added goods? Do they originate

from different production systems such as specialised workshops, or do they originate from domestic units and then

pooled for exchange? Also, how were the resources controlled, but only part of the population or was it a self-service?

During the Late Iron Age, several specialised pottery workshops appeared in areas where unusual raw materials such

as the gabbroic massifs of Saint-Jean-Du-Doigt (Finistère) and Trégomar (Côtes-d'Armor) were found. Their ceramics

are characterised by a large quantity of amphibole grains, and the paste of these vessels possesses a better diffusion of

heat and a greater resistance to thermal shocks. Finally, potters also exploited the alteration products of the serpentinite

deposits of Ty-Lan (Finistère), whose so-called proto-unctuous vases were recognised by a soft and soapy feel, but also

by the large amount of talc inclusions within them, giving them greater impermeability. These production areas distribute

their ceramics, most often shaped locally and for domestic use, over several tens or even hundreds of kilometres,

far beyond the other types of vessels. Furthermore, the greater the distance between the source of raw material and the

final destination of the vases, the more these ceramics are discovered in ritual rather than domestic contexts. This is the

case on the sites of Mez Notariou (Ouessant island, Finistère), Karreg Ar Skariked (Finistère) or the Moutons island

(Finistère).

Furthermore, the use of clay with superior physical and mechanical characteristics has been documented since the

beginning of the Neolithic period on the Armorican massif. This perpetuation in the use of these raw materials tends

to show that craftspeople quickly understood the interest of these raw materials and sought out such clays. Moreover,

it is rare to observe in this region such practices for the other clayey raw materials, whose sources are more common

and numerous.

It seems, therefore, that as in the case of lithic materials, uncommon clays acquire a different status according to their

physical and mechanical quality, as well as their remoteness from the deposit. In this paper, we propose to engage in a

reflection on the raw material used to shape ceramics as one of the factors that determine the diffusion of these products.

Finally, the criteria by which consumers could "identify" the raw materials used, not easily differentiated by the

naked eye, need to be defined. We can assume that the reputation of the fencers and/or potters could be an important

criterion based on an established trust between the consumer and the producer. However, the mass of the vessel and its

soapy feel, in particular for pottery with talc inclusions would also have been used to determine quality. This problematic

needs to be explored further, notably by studying pottery discovered in ritual contexts and tombs but also in areas

where other prestigious artefacts were produced (such as the Grand Pressigny region). It will thus be possible to reach

a greater understanding of the circulation of ceramics but also to shed new light on the occupations where these types

of vases are found.

ceramics pastes opens a new path in the determination of the origins of

raw materials. Indeed, by this method it is possible to distinguish different

clay sources in cases when traditional methods (petrographic observation

and global chemical analysis) cannot. This approach is based on

comparisons of the chemical signatures of mineral inclusions present in

the pottery and the same mineral species in the mother rocks. This paper

will present advancements made in this field, in order to sensitize

archaeologists to this method that has only been slightly exploited and

which results can throw more light on micro-regional paleo-economic

problematics.

Based on several examples form the Armorican Massif (France), from a chronological period extending from the Neolithic to the Second Iron Age, we will see that the comparison of the chemical signatures of minerals included in fired clay with those from earth and source rocks

enables us to distinguish productions and to accurately trace the sources of the raw materials used by potters.

L’étude de la céramique de la Batterie Basse dans la Manche a montré de nouveau que la présence

de bioclastes dans les pâtes des céramiques de la Protohistoire est un phénomène très courant en

Normandie contrairement à la Bretagne, où en l’état actuel des connaissances, un seul individu daté

de l’âge du Fer a été décrit. Ces bioclastes, le plus souvent des fragments de bivalves, sont des éléments

non plastiques, soit présents naturellement dans les argiles sous forme de fossiles, soit sous forme de

coquilles contemporaines qui ont été pilées par les artisans afin de les incorporer dans leurs pâtes

pour modifier les caractéristiques techniques des argiles.

Ce travail a pour objectif de sensibiliser les archéologues à ce type de mobilier et d’évaluer les réponses

pouvant être apportées par les pétro-céramologues concernant l’origine de ces céramiques bien

spécifiques, autant par étude en lame mince, que par des analyses géochimiques. À travers l’étude

des différents sites de l’ouest de la France de l’âge du Bronze et de l’âge du Fer il s’agit également

d’étudier les échanges entre Bretagne et Normandie dans un premier temps, mais également de

mettre en lumière de possibles liens culturels à l’âge du Fer entre le continent, ici la Normandie, et

les îles britanniques.

Abstract:

The study of the ceramics from the site of the Batterie Basse in the region of Manche, shows again that the

presence of bioclasts in the clays of protohistoric ceramics is a very common phenomenon in Normandy

unlike in Brittany, where in the current state of knowledge only one individual from the Iron Age has been

described. These bioclasts, mostly fragments of bivalves, are non-plastic elements naturally present

in the clays, either in the form of fossils, either in the form of contemporary shells, or are incorporated

by the craftsmans after being pounded to modify the technical characteristics of the clays.

The aim of this work is to awareness the archaeologists to this type of artefacts and to evaluate

the response that could be brought by the petro-ceramologists concerning the origin of these very

specific ceramics, as per study thin blade, as geochemical analysis. Through the study of different

sites in western France, dating from the Bronze Age to the Iron Age, it is also possible to study the

interaction between Brittany and Normandy in a first time, but also to highlight possible cultural ties

to the Iron Age between the mainland, here the Normandy, and the British Isles.

Ces questionnements seront développés autour d'un type bien particulier de céramiques, appelées proto-onctueuses du fait de leur texture douce et savonneuse au toucher et dont la zone d'extraction de matière première est bien connue. Nous nous intéresserons plus particulièrement aux découvertes en contexte insulaire des sites de Karreg Ar Skariked (Cléden Cap-Sizun, 29) et de l'Île aux Moutons (Fouesnant, 29) et d'un îlot satellite de l'Île aux Moutons.

Afin de mettre en avant de nouvelles données pour répondre à ces problématiques, nous avons fait appel à plusieurs méthodes d'analyses archéométriques, qui se sont déroulées à différentes échelles d'observations et d'analyses en complément de l'étude typologique. Nous avons notamment étudié les inclusions non plastiques dans les pâtes servant à la confection des céramiques, permettant de reconnaître le type de roche dont est issue l’argile par les processus d’altérations ou encore des analyses chimiques globales et ponctuelles afin d'identifier des groupes de pâtes similaires ayant une même origine géologique et géographique. De telles analyses ont été réalisées sur un ensemble de sites de différentes périodes (allant du Néolithique à l'époque Gallo-romaine) dans le cadre d'une thèse. Nous présenterons notre réflexion concernant les sites de l'âge du Fer, qui voit notamment l'apparition en Bretagne de centres spécialisés dans le production de céramique, grâce à l’arrivée de nouvelles technologies comme le tour et plus tard le tour rapide qui permettra aux artisans de faire évoluer leurs productions, stylistiquement ainsi que quantitativement mais également vers des formes plus standardisées (Pierret 2001). Ces nouvelles techniques de production vont fournir aux artisans un gain de temps important qui modifiera les impératifs socio-économiques de l'époque, différents d’une production par moulage ou montage aux boudins.

À travers cette communication, les auteurs souhaitent présenter une première approche des modes d’occupation le long du littoral de la Manche et de l'Atlantique au premier millénaire avant notre ère. C'est l'occasion d'actualiser la vision du peuplement de l'Ouest de la France à l'âge du Fer où les occupations littorales ont parfois manqué dans certaines synthèses récentes.

Le cadre géographique retenu sera l'actuelle région administrative Bretagne qui présente 2700 km de linéaire côtier, si l'on inclut toutes les indentations des îles et du littoral continental. La longueur des côtes prises ici en compte permettra d'analyser les systèmes de peuplement à différentes échelles géographiques. Cette analyse repose sur une reprise critique de la documentation archéologique recensée sur cette partie du littoral, y compris les estuaires et rias qui en sont le prolongement naturel. Par ailleurs, cette contribution complète la synthèse consacrée dédiée aux îles bretonnes de plein océan (Le Bihan et al., ce volume).

The islands of the Glénan archipelago and Moutons Island (Fouesnant, Finistère) have been the subject of archaeological references since the eighteenth century and inventories in the early twentieth century, in which numerous indices of human presence at the end of Prehistory are mentioned. Researches drawn by Marthe and Saint-Just Péquart in 1926-27 confirmed the attractiveness of Neolithic and Gaulish people for these island areas. A rediscovery of these pioneering works and new exploration campaigns have resulted in a series of planned excavations, leading to the discovery of important set of constructions remains and objects. They show an almost continuous occupation, from the Mesolithic until the end of the Iron Age. Following a first major historiographical documentary work, the integration of the surveys data and of the multidisciplinary studies drawn after the recent fieldwork, fully completed for that is the Iron Age, are still in progress for the earlier periods; this allows to propose an initial assessment. The nature and function of the different sites have been identified and the important part played by these insular places could be considered in a renewed perspective. If discreet for the Palaeolithic period, the occupation of the Moutons Island and Glénan archipelago will intensify through the Neolithic and the Bronze Age, to become very dense at the end of the Iron Age. The perception of space seems to be is sometimes very different and sometimes strikingly similar. The marine submersion of the older sites can probably explain the low presence of hunter-gatherers on the islands, effective at the end of the Mesolithic. Still elusive because of the pending completion of analysis, the prehistoric Neolithic occupation is dense and characterized by the construction and use of megaliths and the development of specialized activities. The link with the neighbouring coastal communities is strong. It was not until the beginning of the Metal Ages to the occupation of the island territory is extensive. In the Bronze Age, the occupation of the entire complex Moutons-Glénan islands is effective and increases at the beginning of the first millennium, when the cemeteries occupy a large part of the archipelago. At the end of La Tène period, the Glénan and Moutons islands are densely occupied and could be integrated into a long-distance exchange networks. The strategic geographical position, on the one hand between the continent and the ocean and the other south of the tip of Brittany, gives them, from the Late Prehistoric time, a key role in the development of the Atlantic societies.

Résumé :

Les îles de l’archipel des Glénan et l’île aux Moutons (Fouesnant, Finistère) ont fait l’objet de mentions archéologiques depuis le XVIIIème siècle et d’inventaires au début du XXème siècle, dans lesquels est déjà mentionné un nombre important d’indices d’une fréquentation humaine dès la fin de la Préhistoire. Les recherches entreprises par Marthe et Saint-Just Péquart en 1926-27 confirmèrent l’attrait des hommes du Néolithique et des Gaulois pour ces espaces insulaires. Une redécouverte de ces travaux pionniers et de nouvelles campagnes de prospection ont donné lieu à une série de fouilles programmées, ayant permis la découverte d’importants vestiges immobiliers et mobiliers. Ils montrent une occupation quasi continue du Mésolithique jusqu’à la fin de l’époque gauloise. Suite à un premier important travail documentaire historiographique, l’intégration des données de prospections et des études pluridisciplinaires menées à l’issue des récents travaux de terrain, totalement achevée pour de ce qui est de l’Age du Fer, est encore en cours pour les époques antérieures, ce qui permet de dresser un premier bilan. La nature et la fonction des différents sites ont pu être précisées et la place importante de ces espaces insulaires remise en perspective. Très discrète au Paléolithique, la fréquentation de l’île aux Moutons et de l’archipel des Glénan va s’intensifier au Néolithique moyen et à l’Age du Bronze, pour devenir très dense à la fin de l’Age du Fer. La perception des espaces insulaires s’avère tantôt très différente, d’un contexte à l’autre, tantôt étonnamment similaire. La submersion des sites les plus anciens peut sans doute permettre d’expliquer la faible présence des chasseurs-cueilleurs sur l’île, effective dès à partir de la fin du Mésolithique. Encore difficile à appréhender dans l’attente de l’achèvement des analyses , l’occupation préhistorique néolithique est dense et se caractérise par la construction puis l’utilisation de mégalithes et le développement d’activités spécialisées. Le lien avec les communautés littorales voisines est fort. Il faut attendre les débuts des âges des Métaux pour que l’occupation du territoire insulaire soit extensive. A l’Age du Bronze, l’occupation de la totalité du complexe Glénan-Moutons est effective et s’accentue au début du 1er millénaire, où les nécropoles occupent un large territoire sur l’archipel. A la fin de La Tène, les Glénan et les Moutons sont densément occupés et pourraient s’intégrer au cœur de réseaux d’échanges à longue distance. La position géographique stratégique, d’une part entre le continent et l’Océan et, d’autre part, au sud de la pointe bretonne, leur confère depuis la fin de la Préhistoire un rôle déterminant dans le développement des sociétés atlantiques.

Cet article vise à préciser la contribution de l’archéologie à l’étude des dynamiques insulaires, sur la base de l’analyse de l’évolution culturelle et du peuplement (insularité vs contacts) combinée à des approches environnementales de l’évolution des paysages côtiers. D’un point de vue méthodologique, un tel processus est basé sur une approche interdisciplinaire couvrant plusieurs domaines tels que les campagnes de terrain (fouilles archéologiques et prospections systématiques), des études historiques pour les périodes plus récentes (textes), mais aussi, pour une part, le recours à la biologie et aux sciences de la terre. À titre d’illustration des questions développées dans le cadre géographique de la façade atlantique de l’Europe, les auteurs présentent les principaux résultats des enquêtes archéologiques de longue haleine menées sur l’île de Groix (Morbihan). Mettant l’accent sur l’une des plus grandes îles de l’Ouest de la France, aujourd’hui localisée à 5,5 km des côtes les plus proches, est peuplée depuis le début Préhistoire et les chercheurs peuvent y documenter l’évolution de la relation entre l’homme et l’environnement maritime (de l’exploitation des ressources à la navigation ...) à différentes échelles de temps, du début du Paléolithique jusqu’à l’époque Moderne.

Abstract:

This paper aims to discuss the contribution of archaeology to ancient island dynamics; this includes studying the cultural evolution and development of settlement (‘islandness’ vs. contacts), combined with environmental approaches dealing with coastal landscape changes. From a methodological point of view, such an archaeological process is based on an interdisciplinary approach covering several research fields such as prehistory and archaeology (excavations and systematic surveys), historical studies (texts), biology and the earth sciences.

As an illustration of the issues developed in the geographical context of the European Atlantic Arc, the authors present the main results of long-continued investigations on Groix Island (Brittany, France). Groix Island, which is situated 5.5 km from the nearest coast, is among the larger islands of Western France (1520 ha/15 km²) and has been populated since early Prehistory. Therefore, this island documents the evolution of the relationship between human groups and the maritime environment (resource exploitation, navigation, etc.) on various timescales from the early Palaeolithic up until to the Middle Ages.

Les analyses pétrographiques des céramiques nous permettent de connaître les origines géologiques des matières premières et donc leurs lieux de production. Cette méthode, appliquée de manière diachronique à plusieurs occupations du complexe de Houat, Hoedic et de Belle-Île-en-Mer, nous fournit ainsi un aperçu des échanges et des liens qu’ont pu avoir ces populations avec leurs voisins : s’agissait-il d’îles formant des noeuds de communication et d’échange, ou des « cul-de-sac » ? Y-a-t-il eu des phases de repli et d’ouverture, et si oui, pouvons-nous les apercevoir sur ce laps de temps relativement long par le biais des seules productions céramiques ? L’évolution des techniques a-t-elle eu un impact sur l’évolution des échanges ?

Abstract

The petrographic analysis of ceramics allows us to trace the geological provenance of raw materials and thus their production sites. When applied diachronically to several occupations belonging to the complex group of Houat, Hoedic and Belle-Ile-en-Mer, this method provides an overview of exchanges and contacts that may have taken place between these island populations and their neighbours: did the islands form nodes of communication and exchange or do they represent dead-ends? Were there phases of retreat and opening up and, if so, can we see evidence for these changes over a relatively long time period by considering solely the ceramic productions? Did the evolution of technology have an impact on the development of trade?

of the realisation, the time and energy invested in the making of the object; but also by its use, ornamentation, form or

content. However, new research on the raw materials used in the ceramics of the Armorican massif (western France)

has demonstrated the distribution of specific types of pastes (the result of the alteration of the crystalline base) over

distances superior to those observed for potteries shaped from common clay. These raw materials are characterised by

their rarity and by the presence of mineral inclusions conferring particular physical and mechanical properties to the

ceramics, such as better resistance to thermal shocks, a more homogeneous diffusion of heat or even greater impermeability.

Taking these observations into consideration, can ceramics be exchanged in relation to the use of a specific raw

material, and in this case, be considered as a value-added object and thus exchanged as such as is the case for lithic

artefacts such as jadeite axes, or even variscite beads and pendants?

In order to develop new research prospects centred around the production and diffusion of ceramics in western France,

the results of the petrographic studies of the potteries of several occupations located on the Armorican massif and dating

from the Late Neolithic (3800–2800 BC) and the Late Iron Age (450–50 BC) will be presented. This massif has the

particularity of being composed of a great diversity of magmatic and metamorphic rocks, such as granite, micaschiste

or gabbro, and the potters had at their disposal a multitude of types of clay. These raw materials possess mineral

inclusions having physical and mechanical characteristics, which can influence the quality of the pastes. For the Late

Neolithic, we observed the privileged diffusion over more than 50 km of ceramics shaped using clays containing the

alterations of talcschistes, which are only found on the island of Groix (Morbihan). These exchanged ceramics have

been found on sites with specialised activities, such as Saint-Nicolas-des-Glénan (Glénan Archipelago, Finistère) and

Er Yoh (Houat Island, Morbihan). The vessels are characterised by an abundance of sheaves of talc within their pastes,

giving the containers a greater impermeability, and blue amphibole grains, confirming that the island of Groix is the

origin of the raw material. The status of value-added goods has an influence on the management of the raw materials

and pottery production. Indeed, we can argue that the ceramics of this period were produced in the household and were

distributed within family units or at a community level to meet subsistence needs. However, what about the potteries

made with specific raw materials and used in exchange systems to obtain other value-added goods? Do they originate

from different production systems such as specialised workshops, or do they originate from domestic units and then

pooled for exchange? Also, how were the resources controlled, but only part of the population or was it a self-service?

During the Late Iron Age, several specialised pottery workshops appeared in areas where unusual raw materials such

as the gabbroic massifs of Saint-Jean-Du-Doigt (Finistère) and Trégomar (Côtes-d'Armor) were found. Their ceramics

are characterised by a large quantity of amphibole grains, and the paste of these vessels possesses a better diffusion of

heat and a greater resistance to thermal shocks. Finally, potters also exploited the alteration products of the serpentinite

deposits of Ty-Lan (Finistère), whose so-called proto-unctuous vases were recognised by a soft and soapy feel, but also

by the large amount of talc inclusions within them, giving them greater impermeability. These production areas distribute

their ceramics, most often shaped locally and for domestic use, over several tens or even hundreds of kilometres,

far beyond the other types of vessels. Furthermore, the greater the distance between the source of raw material and the

final destination of the vases, the more these ceramics are discovered in ritual rather than domestic contexts. This is the

case on the sites of Mez Notariou (Ouessant island, Finistère), Karreg Ar Skariked (Finistère) or the Moutons island

(Finistère).

Furthermore, the use of clay with superior physical and mechanical characteristics has been documented since the

beginning of the Neolithic period on the Armorican massif. This perpetuation in the use of these raw materials tends

to show that craftspeople quickly understood the interest of these raw materials and sought out such clays. Moreover,

it is rare to observe in this region such practices for the other clayey raw materials, whose sources are more common

and numerous.

It seems, therefore, that as in the case of lithic materials, uncommon clays acquire a different status according to their

physical and mechanical quality, as well as their remoteness from the deposit. In this paper, we propose to engage in a

reflection on the raw material used to shape ceramics as one of the factors that determine the diffusion of these products.

Finally, the criteria by which consumers could "identify" the raw materials used, not easily differentiated by the

naked eye, need to be defined. We can assume that the reputation of the fencers and/or potters could be an important

criterion based on an established trust between the consumer and the producer. However, the mass of the vessel and its

soapy feel, in particular for pottery with talc inclusions would also have been used to determine quality. This problematic

needs to be explored further, notably by studying pottery discovered in ritual contexts and tombs but also in areas

where other prestigious artefacts were produced (such as the Grand Pressigny region). It will thus be possible to reach

a greater understanding of the circulation of ceramics but also to shed new light on the occupations where these types

of vases are found.

ceramics pastes opens a new path in the determination of the origins of

raw materials. Indeed, by this method it is possible to distinguish different

clay sources in cases when traditional methods (petrographic observation

and global chemical analysis) cannot. This approach is based on

comparisons of the chemical signatures of mineral inclusions present in

the pottery and the same mineral species in the mother rocks. This paper

will present advancements made in this field, in order to sensitize

archaeologists to this method that has only been slightly exploited and

which results can throw more light on micro-regional paleo-economic

problematics.

Based on several examples form the Armorican Massif (France), from a chronological period extending from the Neolithic to the Second Iron Age, we will see that the comparison of the chemical signatures of minerals included in fired clay with those from earth and source rocks

enables us to distinguish productions and to accurately trace the sources of the raw materials used by potters.

L’étude de la céramique de la Batterie Basse dans la Manche a montré de nouveau que la présence

de bioclastes dans les pâtes des céramiques de la Protohistoire est un phénomène très courant en

Normandie contrairement à la Bretagne, où en l’état actuel des connaissances, un seul individu daté

de l’âge du Fer a été décrit. Ces bioclastes, le plus souvent des fragments de bivalves, sont des éléments

non plastiques, soit présents naturellement dans les argiles sous forme de fossiles, soit sous forme de

coquilles contemporaines qui ont été pilées par les artisans afin de les incorporer dans leurs pâtes

pour modifier les caractéristiques techniques des argiles.

Ce travail a pour objectif de sensibiliser les archéologues à ce type de mobilier et d’évaluer les réponses

pouvant être apportées par les pétro-céramologues concernant l’origine de ces céramiques bien

spécifiques, autant par étude en lame mince, que par des analyses géochimiques. À travers l’étude

des différents sites de l’ouest de la France de l’âge du Bronze et de l’âge du Fer il s’agit également

d’étudier les échanges entre Bretagne et Normandie dans un premier temps, mais également de

mettre en lumière de possibles liens culturels à l’âge du Fer entre le continent, ici la Normandie, et

les îles britanniques.

Abstract:

The study of the ceramics from the site of the Batterie Basse in the region of Manche, shows again that the

presence of bioclasts in the clays of protohistoric ceramics is a very common phenomenon in Normandy

unlike in Brittany, where in the current state of knowledge only one individual from the Iron Age has been

described. These bioclasts, mostly fragments of bivalves, are non-plastic elements naturally present

in the clays, either in the form of fossils, either in the form of contemporary shells, or are incorporated

by the craftsmans after being pounded to modify the technical characteristics of the clays.

The aim of this work is to awareness the archaeologists to this type of artefacts and to evaluate

the response that could be brought by the petro-ceramologists concerning the origin of these very

specific ceramics, as per study thin blade, as geochemical analysis. Through the study of different

sites in western France, dating from the Bronze Age to the Iron Age, it is also possible to study the

interaction between Brittany and Normandy in a first time, but also to highlight possible cultural ties

to the Iron Age between the mainland, here the Normandy, and the British Isles.

Ces questionnements seront développés autour d'un type bien particulier de céramiques, appelées proto-onctueuses du fait de leur texture douce et savonneuse au toucher et dont la zone d'extraction de matière première est bien connue. Nous nous intéresserons plus particulièrement aux découvertes en contexte insulaire des sites de Karreg Ar Skariked (Cléden Cap-Sizun, 29) et de l'Île aux Moutons (Fouesnant, 29) et d'un îlot satellite de l'Île aux Moutons.

Afin de mettre en avant de nouvelles données pour répondre à ces problématiques, nous avons fait appel à plusieurs méthodes d'analyses archéométriques, qui se sont déroulées à différentes échelles d'observations et d'analyses en complément de l'étude typologique. Nous avons notamment étudié les inclusions non plastiques dans les pâtes servant à la confection des céramiques, permettant de reconnaître le type de roche dont est issue l’argile par les processus d’altérations ou encore des analyses chimiques globales et ponctuelles afin d'identifier des groupes de pâtes similaires ayant une même origine géologique et géographique. De telles analyses ont été réalisées sur un ensemble de sites de différentes périodes (allant du Néolithique à l'époque Gallo-romaine) dans le cadre d'une thèse. Nous présenterons notre réflexion concernant les sites de l'âge du Fer, qui voit notamment l'apparition en Bretagne de centres spécialisés dans le production de céramique, grâce à l’arrivée de nouvelles technologies comme le tour et plus tard le tour rapide qui permettra aux artisans de faire évoluer leurs productions, stylistiquement ainsi que quantitativement mais également vers des formes plus standardisées (Pierret 2001). Ces nouvelles techniques de production vont fournir aux artisans un gain de temps important qui modifiera les impératifs socio-économiques de l'époque, différents d’une production par moulage ou montage aux boudins.

À travers cette communication, les auteurs souhaitent présenter une première approche des modes d’occupation le long du littoral de la Manche et de l'Atlantique au premier millénaire avant notre ère. C'est l'occasion d'actualiser la vision du peuplement de l'Ouest de la France à l'âge du Fer où les occupations littorales ont parfois manqué dans certaines synthèses récentes.

Le cadre géographique retenu sera l'actuelle région administrative Bretagne qui présente 2700 km de linéaire côtier, si l'on inclut toutes les indentations des îles et du littoral continental. La longueur des côtes prises ici en compte permettra d'analyser les systèmes de peuplement à différentes échelles géographiques. Cette analyse repose sur une reprise critique de la documentation archéologique recensée sur cette partie du littoral, y compris les estuaires et rias qui en sont le prolongement naturel. Par ailleurs, cette contribution complète la synthèse consacrée dédiée aux îles bretonnes de plein océan (Le Bihan et al., ce volume).

The islands of the Glénan archipelago and Moutons Island (Fouesnant, Finistère) have been the subject of archaeological references since the eighteenth century and inventories in the early twentieth century, in which numerous indices of human presence at the end of Prehistory are mentioned. Researches drawn by Marthe and Saint-Just Péquart in 1926-27 confirmed the attractiveness of Neolithic and Gaulish people for these island areas. A rediscovery of these pioneering works and new exploration campaigns have resulted in a series of planned excavations, leading to the discovery of important set of constructions remains and objects. They show an almost continuous occupation, from the Mesolithic until the end of the Iron Age. Following a first major historiographical documentary work, the integration of the surveys data and of the multidisciplinary studies drawn after the recent fieldwork, fully completed for that is the Iron Age, are still in progress for the earlier periods; this allows to propose an initial assessment. The nature and function of the different sites have been identified and the important part played by these insular places could be considered in a renewed perspective. If discreet for the Palaeolithic period, the occupation of the Moutons Island and Glénan archipelago will intensify through the Neolithic and the Bronze Age, to become very dense at the end of the Iron Age. The perception of space seems to be is sometimes very different and sometimes strikingly similar. The marine submersion of the older sites can probably explain the low presence of hunter-gatherers on the islands, effective at the end of the Mesolithic. Still elusive because of the pending completion of analysis, the prehistoric Neolithic occupation is dense and characterized by the construction and use of megaliths and the development of specialized activities. The link with the neighbouring coastal communities is strong. It was not until the beginning of the Metal Ages to the occupation of the island territory is extensive. In the Bronze Age, the occupation of the entire complex Moutons-Glénan islands is effective and increases at the beginning of the first millennium, when the cemeteries occupy a large part of the archipelago. At the end of La Tène period, the Glénan and Moutons islands are densely occupied and could be integrated into a long-distance exchange networks. The strategic geographical position, on the one hand between the continent and the ocean and the other south of the tip of Brittany, gives them, from the Late Prehistoric time, a key role in the development of the Atlantic societies.

Résumé :

Les îles de l’archipel des Glénan et l’île aux Moutons (Fouesnant, Finistère) ont fait l’objet de mentions archéologiques depuis le XVIIIème siècle et d’inventaires au début du XXème siècle, dans lesquels est déjà mentionné un nombre important d’indices d’une fréquentation humaine dès la fin de la Préhistoire. Les recherches entreprises par Marthe et Saint-Just Péquart en 1926-27 confirmèrent l’attrait des hommes du Néolithique et des Gaulois pour ces espaces insulaires. Une redécouverte de ces travaux pionniers et de nouvelles campagnes de prospection ont donné lieu à une série de fouilles programmées, ayant permis la découverte d’importants vestiges immobiliers et mobiliers. Ils montrent une occupation quasi continue du Mésolithique jusqu’à la fin de l’époque gauloise. Suite à un premier important travail documentaire historiographique, l’intégration des données de prospections et des études pluridisciplinaires menées à l’issue des récents travaux de terrain, totalement achevée pour de ce qui est de l’Age du Fer, est encore en cours pour les époques antérieures, ce qui permet de dresser un premier bilan. La nature et la fonction des différents sites ont pu être précisées et la place importante de ces espaces insulaires remise en perspective. Très discrète au Paléolithique, la fréquentation de l’île aux Moutons et de l’archipel des Glénan va s’intensifier au Néolithique moyen et à l’Age du Bronze, pour devenir très dense à la fin de l’Age du Fer. La perception des espaces insulaires s’avère tantôt très différente, d’un contexte à l’autre, tantôt étonnamment similaire. La submersion des sites les plus anciens peut sans doute permettre d’expliquer la faible présence des chasseurs-cueilleurs sur l’île, effective dès à partir de la fin du Mésolithique. Encore difficile à appréhender dans l’attente de l’achèvement des analyses , l’occupation préhistorique néolithique est dense et se caractérise par la construction puis l’utilisation de mégalithes et le développement d’activités spécialisées. Le lien avec les communautés littorales voisines est fort. Il faut attendre les débuts des âges des Métaux pour que l’occupation du territoire insulaire soit extensive. A l’Age du Bronze, l’occupation de la totalité du complexe Glénan-Moutons est effective et s’accentue au début du 1er millénaire, où les nécropoles occupent un large territoire sur l’archipel. A la fin de La Tène, les Glénan et les Moutons sont densément occupés et pourraient s’intégrer au cœur de réseaux d’échanges à longue distance. La position géographique stratégique, d’une part entre le continent et l’Océan et, d’autre part, au sud de la pointe bretonne, leur confère depuis la fin de la Préhistoire un rôle déterminant dans le développement des sociétés atlantiques.

Cet article vise à préciser la contribution de l’archéologie à l’étude des dynamiques insulaires, sur la base de l’analyse de l’évolution culturelle et du peuplement (insularité vs contacts) combinée à des approches environnementales de l’évolution des paysages côtiers. D’un point de vue méthodologique, un tel processus est basé sur une approche interdisciplinaire couvrant plusieurs domaines tels que les campagnes de terrain (fouilles archéologiques et prospections systématiques), des études historiques pour les périodes plus récentes (textes), mais aussi, pour une part, le recours à la biologie et aux sciences de la terre. À titre d’illustration des questions développées dans le cadre géographique de la façade atlantique de l’Europe, les auteurs présentent les principaux résultats des enquêtes archéologiques de longue haleine menées sur l’île de Groix (Morbihan). Mettant l’accent sur l’une des plus grandes îles de l’Ouest de la France, aujourd’hui localisée à 5,5 km des côtes les plus proches, est peuplée depuis le début Préhistoire et les chercheurs peuvent y documenter l’évolution de la relation entre l’homme et l’environnement maritime (de l’exploitation des ressources à la navigation ...) à différentes échelles de temps, du début du Paléolithique jusqu’à l’époque Moderne.

Abstract:

This paper aims to discuss the contribution of archaeology to ancient island dynamics; this includes studying the cultural evolution and development of settlement (‘islandness’ vs. contacts), combined with environmental approaches dealing with coastal landscape changes. From a methodological point of view, such an archaeological process is based on an interdisciplinary approach covering several research fields such as prehistory and archaeology (excavations and systematic surveys), historical studies (texts), biology and the earth sciences.